At the time of the death of Emperor Trajan, on August 11, ad 117, the Roman Empire was in complete turmoil. The two years Trajan had been absent from Rome, spent extending the Empire to the East, meant that the empire was operating without strong imperial leadership at its core, let alone throughout the rest of the Empire to the West. Not surprisingly, then, many of its provinces rebelled, attempting to break free of the taxing Roman overlords. Among them were the Moors of North Africa, the tribes of Britain, the Sarmatians, the Egyptians and Libyans, and Jews. The feeling was deep, such that even Trajan’s recent conquests in Mesopotamia and beyond, failed to quiet it. In short, the empire if it were to endure, needed a saviour. And that was Hadrian.

Hadrian’s rise to power was a serendipitous blend of good fortune and talent. Born in Italica in Spain in ad 76, Hadrian had close family ties with Trajan’s Ulpius family who lived there: Trajan and Hadrian were cousins. These close ties gave Hadrian a rapid rise through the ranks of the military. Adding to this, when Trajan was adopted by Nerva and proclaimed as Nerva’s heir to the purple, Hadrian was appointed governor of Upper Germany, at the head of one of Rome’s most powerful legionary armies. The message Nerva and Trajan were sending was clear: at some point Rome’s future would lay with Hadrian.

However, Hadrian was not officially adopted as heir by Trajan until just two days before his death on August 9, ad 117. It is possible that Trajan was in denial of his humanity until he was actually dying. But it was a masterstroke to appoint Hadrian as his successor, as things transpired. For, luck aside, Hadrian managed to not only save the empire but transform it into a thriving entity, as never before.

Of course, not everybody was happy with Trajan’s choice. Within the Roman Senate there were several plots hatched to deny Hadrian. But Hadrian dealt with them with a shrewd carrot-and-stick approach. He pardoned some plotters, advertising to all Romans his goodwill to those whom he felt deserved it, while executing others, including four former-consuls, sending a clear message of the consequences of treason.

Having dealt with the plots, Hadrian set about restoring civil and political order. First, he evacuated Rome’s army from beyond the Euphrates, redeploying it to those provinces in rebellion, where in quick time revolt was quelled.

Next, he set about stimulating the economy, beginning with the paying off of public and private debt. And not just in Rome. Throughout Italy and the provinces, he literally burned forms of indebtedness, a symbolism not lost on the people, aimed at restoring confidence. Next, he replenished the Senate Treasury, then granted funding to some of its bankrupt senators and lastly, increasing the pay of public servants. This immediately helped the state to more efficiently manage and support itself.

However, true power within the empire resided with Rome’s armies. One needed its support to rule. So, Hadrian then set about reforming the army, increasing its prestige, in doing so ensuring the military lent him its allegiance and remained loyal. He also improved its battle-readiness and training, while better arming and supplying it, with, for the first time, the Roman state funding it; he demonstrated his own generalship, even to marching on foot at the head of his legions as a legionnaire, enduring the same privations as his men; and he took the time to visit sick and injured soldiers in their quarters. Such measures greatly improved discipline and morale among soldiers and officers, but above all, he never went to war unless it was necessary. There would be no ruinous adventures like those of Trajan under Hadrian.

His policy of not embarking on wars of conquest had a far-reaching legacy. For example, it left us the famous landmark in northern Britain, Hadrian’s Wall. A wall of stone and forts runs some 140 km (80 miles) across Britain, which Hadrian built during his visit to the island in ad 122.

But this wall was not only built to defend the Roman Empire from the Picts and other tribes to the north in what is now Scotland. The wall was a symbol of the end of further conquest. Just as Alexander the Great marked the end of his conquests on the Hydaspes River in India by sacrificing to the Greek gods Neptune and Oceanus, now Hadrian himself, almost 450 years later, also sacrificed to these same deities in person, on the British frontier by the Tyne River, and immediately ordered his famous wall to be built from that spot. Building the wall was a huge undertaking: built from Maryport on the west coast all the way to Wallsend on the east coast, it was some 3 metres (10 feet) broad and 4.2 metres (14 feet) high, with a clay and rubble core and encased with cut stone, and defensive battlements erected and ditches dug along its length. This was a monument to Hadrian’s break with Rome’s monumental conquering past.

But this policy had another, more valuable result: it made the empire wealthier. With the empire now consolidated and peace assured, business flourished. It became the greatest manufacturing and trading giant the world had seen.

Hadrian was keen to maintain that image of greatness, as well as to advertise it. In order to unite the empire under his rule and promote trade, he spent a lot of time touring all quarters of the empire. He travelled to Germany, Britain, Gaul, Greece, Asia, Syria, Sicily, and Egypt and North Africa—more than any other emperor had. As a result, morale was lifted throughout the entire Roman Empire and economic prosperity soared.

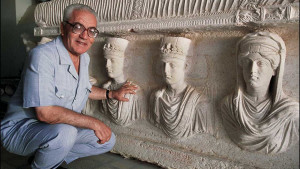

Of great significance was his visit to Palmyra in Syria, the great trading centre at the western terminus of the Silk Road and client-state of Rome. At its zenith Palmyra had a population of some 200,000. Located between the Roman and Parthian Empires, Palmyrenes enjoyed the lucrative status as trade middlemen between the two greatest realms in the world at that time. Hadrian’s visit might have been to promote Rome’s economic interests there, but the overall feeling in the city was celebration of Hadrian himself. This is attested to in an inscription from Palmyra that commemorates the visit, describing him as “the God Hadrian” (IGR III 1054). Coin-like tokens found by archaeologists in Palmyra depicting Hadrian’s wife Sabina indicate that she accompanied her husband and received similar adulation. Today, Palmyra is in ruins, but the size and splendour of those ruins reflect its once proud history.

Hadrian was keen to inform rulers of cities, kingdoms and empires beyond the Empire of Rome’s economic credentials too. Once, when the king of Parthia sent Hadrian a gift of gold-embroidered cloaks, Hadrian made light of this by sending 300 criminals into the arena to fight to the death wearing similar gold-embroidered cloaks. Not surprisingly, the rulers of the kingdoms outside the Roman Empire rushed to Hadrian’s court in order to become friends and to sample Rome’s wealth for themselves, including those as far away as the Caspian Sea, and Bactria in present-day Pakistan.

Hadrian’s wall. Stretching for 120 kilometres from the Solway Firth on the west coast of Britain to the River Tyne on the east coast, Hadrian’s Wall was a line of fortifications across northern England making it the largest structure ever made by the Romans. This wall not only defended the Roman Empire from aggressive tribes of Scotland, it was symbolic of the end of further Roman conquest.

Hadrian’s wall. Stretching for 120 kilometres from the Solway Firth on the west coast of Britain to the River Tyne on the east coast, Hadrian’s Wall was a line of fortifications across northern England making it the largest structure ever made by the Romans. This wall not only defended the Roman Empire from aggressive tribes of Scotland, it was symbolic of the end of further Roman conquest.

But Hadrian was no pushover. Once, a man with grey-hair came to Hadrian with a request for money, and when that same man returned the following day with dyed hair to disguise himself asking the same request, Hadrian simply, but emphatically, replied, “I have already refused this to your father!”

In respect to religion, Hadrian was a staunch observer of Rome’s pagan traditions. But this brought him into conflict with the Jews. Disdainful of the Jewish religion, in ad 132, Hadrian set about building a temple to Jupiter in Jerusalem where the Jewish Temple, destroyed by Titus, had once stood. The Jews rushed to arms under the leader Simon Bar Kokhba, a self-styled messiah who carried on a guerrilla war with Hadrian’s disciplined legions in the hope of toppling Rome and creating a temporal empire of his own. Some of Bar Kokhba’s letters to his Jewish lieutenants survive, being famously discovered by chance during excavation in a cave in the Judean wilderness by an archaeological team led by Jewish archaeologist Yigael Yadin in 1960. These letters show that Bar Kokhba employed a mixture of intense religious zealotry and harsh military despotism in his rule over other Jews and throughout his war with Rome. In one letter to Yehonathan and Masabala, two of his army officers, he writes:

“Let all men from Tekoa and other places who are with you, be sent to me without delay. And if you shall not send them, let it be known to you, that you will be punished.”

In another letter to his officer Yeshua ben Galgoula, he writes in menacing terms:

“I take heaven to witness against me that unless you mobilise the Galileans who are with you every man, I will put fetters on your feet as I did to ben Aphlul.”

Such violent religious fervour worked in Bar Kokhba’s interests for a time. But, progressing city by city, and fortress by fortress, Hadrian’s armies, using guerrilla tactics together with traditional Roman strategies and fighting techniques, mercilessly crushed this revolt within a few years.

Of course, Hadrian believed that the downfall of the Jews was the fate that the Roman gods had planned all along for them.

Temple of Hadrian in Ephesus, Turkey The remains of this temple were unearthed in 1956 and rebuilt with some supplementation using modern building material, so as to reproduce the building’s precise appearance more fully. An inscription tells us the temple was erected by Publius Quinctilius, who dedicated it to Emperor Hadrian on the occasion of his visit to the city in AD 128.

Temple of Hadrian in Ephesus, Turkey The remains of this temple were unearthed in 1956 and rebuilt with some supplementation using modern building material, so as to reproduce the building’s precise appearance more fully. An inscription tells us the temple was erected by Publius Quinctilius, who dedicated it to Emperor Hadrian on the occasion of his visit to the city in AD 128.

Bar Kokhba papyrus letter Letters such as this one, found in a Judean cave by Yigael Yadin, reveal rebel leader Simon Bar Kokhba’s harsh military despotism.

Bar Kokhba papyrus letter Letters such as this one, found in a Judean cave by Yigael Yadin, reveal rebel leader Simon Bar Kokhba’s harsh military despotism.

But many Jews no doubt saw Hadrian’s own downfall that followed a few years later, in much the same circumstances as Herod the Great’s, as their own God’s divine retribution for Hadrian’s destruction of the Promised Land. As Herod did before him, when Hadrian aged he became extremely paranoid about plots and schemes to kill and replace him. After becoming sick almost to the point of death, at the age of 60, there was naturally some talk among Rome’s senators and generals concerning his replacement, as one would expect. But Hadrian recovered, and he was irate at this.

Although Hadrian had survived this sickness, his health steadily deteriorated, and he saw the glaring need to appoint a successor after all. Accordingly, he chose Arrius Antoninus‚ better known as Antoninus Pius, to be his successor, and ordered Antoninus to also adopt Marcus Antoninus and his younger brother Annius Verus. These two brothers are better known to us as Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus.

The rest, as they say, is history. Antoninus Pius would prove to be a wise and peaceful ruler and under him the Empire flourished as it had under Hadrian, and as for his two adoptive successors, Marcus Aurelius would also prove to be one of Rome’s wisest emperors and Verus one of its most spirited. For all of Hadrian’s faults as a ruler, his choice in his successors proved again that his adoption by Trajan was not simply luck, but rather was due to his intelligence and an ability to rule.

Hadrian’s Library Hadrian was an ardent admirer of Greek culture and regularly visited Athens. Wanting to make Athens the cultural capital of the Roman Empire, Hadrian initiated several building projects in the city, including the construction of this large library.

Hadrian’s Library Hadrian was an ardent admirer of Greek culture and regularly visited Athens. Wanting to make Athens the cultural capital of the Roman Empire, Hadrian initiated several building projects in the city, including the construction of this large library.

Castel Sant’Angelo, The Mausoleum of Hadrian, was built in ad 123 by Emperor Hadrian as an enormous tomb for himself and his family. However, he died at the resort of Baiae before its completion, leaving Emperor Antoninus Pius to finish the task. Hadrian was buried twice in different places before finally his ashes was laid to rest in his mausoleum. Over the centuries the mausoleum has been modified many times.

Castel Sant’Angelo, The Mausoleum of Hadrian, was built in ad 123 by Emperor Hadrian as an enormous tomb for himself and his family. However, he died at the resort of Baiae before its completion, leaving Emperor Antoninus Pius to finish the task. Hadrian was buried twice in different places before finally his ashes was laid to rest in his mausoleum. Over the centuries the mausoleum has been modified many times.

As for Hadrian, he passed away on July 10, ad 138, at Baiae on the Bay of Naples, and was buried at Cicero’s villa in Puteoli. But that is not quite the end of Hadrian’s story, for after he died, Arrius Antoninus built a temple for Hadrian at Puteoli, declared him a god there, and established a priesthood and ceremonies there in his honour. These acts made many people regard Antoninus as especially pious—hence the epithet “Pius” was attached to his name. But it is telling that this temple was not built in Rome. For there, after Hadrian’s murderous acts performed as his health failed, the Senate wanted to render his actions invalid, and most senators there did not like the idea of deifying him even when Antoninus Pius asked them to. For all of Hadrian’s love for the Empire, and for all his genius and success in helping it thrive, his paranoid murders resulted in his memory becoming forever tarnished.