Law and order have long underpinned the creation and maintenance of harmonious society. The ancient Egyptians venerated Ma'at the goddess of truth and justice and believed she was the one who, at the moment of her creation, brought order to a chaotic universe. In ancient Greece, Solon of Athens became one of the world’s famous lawgivers; his constitution brought new life to Athenian political and economic law.

The Roman civilisation was also famed for its use of the legal system. From the “Law of the Twelve Tables” to Corpus Juris Civilis, Rome’s influence on western legal thought cannot be overstated.1 So one naturally ponders the question: How far back does this fixation of justice and law go? Was there ever a time in human history where some form of law was not a cornerstone of society? Or, is an intrinsic desire for justice one of the foundational aspects that make us human?

The Law code of Hammurabi is often referred to as the first code of law, dating to around 1934 B.C., but as we shall see, on a much greater scale, it is itself evidence of the existence of laws that extend even further back into antiquity.

King Hummurabi of Babylon

King Hammurabi was part of a dynasty of kings who ruled over Babylon from approximately 1900 B.C. until 1600 B.C.2 Hammurabi’s ancestry was Amorite; his name means “great family,”3 and he often referred to himself as “King of the Amorite land.”4 His father, Sin-muballit, ruled over Babylon for 20 years, after which Hammurabi rose to the throne in 1792 B.C.5 and remained there for 55 years.6 At the time of his ascension, Babylon was neither the grandest nor the most important kingdom in the Middle East, as it would later become. The Babylonian kingdom was some 60 km by 160 km in size and one of many kingdoms of the area.7 Prior to Hammurabi’s reign, debt was a major problem in Babylonian society and relieving the general population of this burden was one of the first things Hammurabi did.8 This is the first indication of the king Hammurabi envisioned himself to be; the good shepherd. By his 33rd year, Hammurabi had become the protector over a very large territory. He had extended his kingdom to cover an area extending from the Persian Gulf coast, to 200 km north along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers—Mesopotamia.9

King Hammurabi promoted his “protector” self-image through a written introduction on his stele. He mentions numerous cities now under his dominion and how he promoted local cults. He states, “I am the shepherd, selected by Enlil.”10 He also addresses the 25 cities under his rule independently, not referring to them as a collective country but respecting each as an entity, each with their own patron deity. He then states that because of his ruling, the occupants of each city have flourished and their gods pleased.11

Hammurabi also made himself very accessible to his general public, which wasn’t at all usual for Mesopotamian kings. Numerous letters indicate that anyone could approach the king when faced with a problem. He would attend the matter personally or direct one of his officials to investigate. This is a reflection of the type of king Hammurabi was; not a king of empty words but a ruler who was passionate about fulfilling his function of king and shepherd over Babylon. Within the context of the character of Hammurabi, we can more readily put his law code into perspective, more accurately understanding the role and purpose of his law-code stele.

The Stele and its purpose

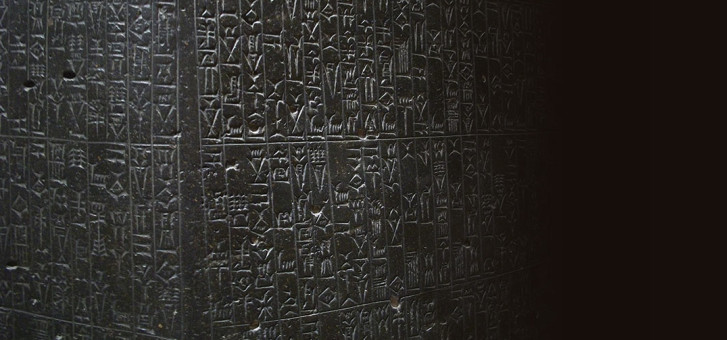

The Law Code of Hammurabi is inscribed on a large black diorite stone. The stone, which is today housed in the Louvre Museum, Paris, stands an impressive 2.25 m high. At the top, it depicts Hammurabi standing facing the Mesopotamian sun god Shamash, who is seated facing left.12 It is inscribed on both sides in the Babylonian language, which is a series of wedges, written left to right, called cuneiform. Egyptologist Gustave Jequier discovered the stone in 1901, during an expedition headed by Jacques de Morgan. The expedition was in the area of ancient Susa, Elam (modern Iran) and it is believed it was removed to there as plunder by the Elamite king Shutruk-Nahhunte in the 12th century B.C.13 It stands today as the longest inscription of all early Mesopotamian history, containing 51 columns. The date given for its composition is sometime after Hammurabi’s 38th year of rule. This we know because many of the cities mentioned as under his rule were not conquered until after this time.14

The inscription of the Law of Hammurabi is made up of three sections: the prologue, a high poetic register of five columns that solidify his connection to the Babylonian gods, legitimating his rule; the core, which contains the list of laws written in prose; and a poetic epilogue praising King Hammurabi in first person.15 And as with many artefacts from the ancient world, we are left to contemplate their purpose.

Understanding the purpose of the Law of Hammurabi is a difficult task because there are no records stating the role of the Law of Hammarabi in everyday Babylonian life. Kathryn Slanski proposes that the text and its image were deliberately designed to incorporate elements of performativity and memorialisation.16 She believes the stele publicised the standards of justice to its audience and at the same time stood as an enduring record of Hummurabi’s role as king.17 Due to the lack of literacy during the time of Hammurabi, it seems doubtful that the purpose of the Law Code of Hammurabi text was to be read by the general civilian. Rather, if the stele were to be presented in a vivid and memorable inauguration ceremony before the citizens of Babylon, its presence alone would stand as an eternal reminder of justice, law and order. Slanski goes one step further and proposes that each time an image is viewed before a Mesopotamian audience, it is as if the scene depicted is being performed,18 an insightful view of the depiction of Hammurabi on the stone itself, adding to its meaning.

As evidence for the performativity of the Law of Ham- marabi she cites the law’s instructions to:

Let any man who has a lawsuit come before my image, the just king, and have my words read out loud: let him hear my precious words, let my monument reveal to him the case. Let him see his judgement, let his heart become soothed.19

The idea that the role of the Law Code of Hammurabi was for the edification and uplifting of the spirits of the community fits with what we know of the character of Hammurabi. A king who showed such concern for the wellbeing of his subjects he would have wanted a public reminder of his just and true character, and placing the Law Code of Hammurabi in a public space would have done precisely that.

The laws of Hummurabi

Hammurabi’s character may be that of the good shepherd of his people, but a closer look at the laws themselves reveal that some of the devil is in the detail. The code is made up of between 275 and 300 laws, the exact number unknown because perhaps as many as another 35 laws were erased and cannot be interpreted.20

All the laws conform to a pattern: the law begins with a conditional, “If . . .” This is followed by a potential action, which is usually a transgression of some sort. Then the consequence of doing the act are outlined, always phrased as commands. For example, the opening law reads:

If a man make a false accusation against a man, putting a ban upon him, and cannot prove it, then the accuser shall be put to death.21

The Law Code of Hammurabi has exceedingly harsh penalties for false accusations and also some rather strange ways of determining one’s innocence, as for the following, second, law:

If a man charge a man of being a sorcerer, and is un- able to sustain such a charge, the one who is accused shall go to the river, he shall plunge himself into the river, and if he sink into the river, his accuser shall take his house. If, however, the river show forth the innocence of this man, and he escape unhurt, then he who accused him of sorcery, shall be put to death, while he who plunged into the river shall appropriate the house of his accuser.22

Such a test of innocence is called the “river ordeal” and was believed by the Babylonians to be divinely accurate.

The death penalty was also enforced for stealing the property of the temple or palace, or if you were the recipient of stolen temple or palace items. Fraud, concealing some- one else’s slave or soldiers who send a substitute to fight for them, all received the death penalty. The underlying philosophy of the Law Code of Hammurabi was “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth.” This is reflected in the law . . .

If a member of the elite blinds the eye of another member of the elite, they shall blind his eye.23

This principle seems a little barbaric when contrasted with western law, perhaps as expressed in the sentiments of US President Abraham Lincoln, who said: “I have always found that mercy bears richer fruits than strict justice.” Hammurabi’s shepherd-like persona would be well and truly diminished knowing that an “eye for an eye” only applies to people of the same social class. For example, Thus, the eye-for-eye principle was not absolute, and punishment was only equal when the parties involved were of equal status.

Amongst all the barbaric ideologies there are some glimpses of rationality. For instance, one such law states:

If a bull, when passing through the street, gore a man and bring about his death, this case has no penalty. If a man’s bull have been wont to gore and they have made known to him his habit of goring, and he have not protected his horns or have not tied him up, and that bull gore the son of a man and bring about his death, he shall pay one-half mana of silver.24

There is a similar law in the United States under the precept that “Every dog is entitled to the first bite free.” This means that the owner is not liable until, as the result of at least one incident, he should know that his dog has a propensity for violence.25 This was not the only law that had similar sentiments to those from later civilisations. The laws governing the protection of property had some similarities to law codes from a much later period. The law of Hammurabi held the local governor and city responsible for losses through highway robbery and this was also the practice in the English Hundred in the time of Edward I.26

Evidence of earlier laws

Is Hammurabi Law, then, the first such code of laws of human history? Vincent’s view27 is that rather than creating new legislation, Law of Hammurabi is a combination of customs and decisions of previous judges into a single body of law. If this is true, then the Law Code of Hammurabi is evidence of legal practices and precepts that extend even further back into antiquity. There is evidence for this, with references to earlier codes appearing in lists produced by the king of Eshnunna in the nineteenth century B.C., 300 years before the time of Hammurabi. For example, part of one such reads:

If an ox is a gorer and the authorities have made this known to its owner, but he does not restrain his ox and it gores someone and thus causes his death, the owner of the ox will pay two-thirds pound of silver.28

So it would appear that King Hammurabi took this pre-existing law and replicated it as follows,

If a man’s ox is a gorer, and the authorities have made known that it is a gorer, but he (the owner) does not cut off its horns or subdue his ox, and that ox gores and kills a free man, he [the owner] will give half a pound of silver.29

Even a superficial comparison reveals the obvious. It looks as though Hammurabi used the simple technique of parallelism to replicate and adapt the already recognised laws into his own style for his kingdom. So if the practice of copying and adapting laws took place in Mesopotamia, then it likely happened elsewhere.

Wright and others claim that the Covenant Code laws of the Old Testament Bible do the same to Hammurabi’s laws as did he to other older Mesopotamian edicts. Which for those who believe in the Bible, begs the question of was the Mosaic Law (the Law of Moses) so influenced by Hammurabi?

It is noted by Wells that the Covenant Code has fewer correspondences with Hammurabi Law than Wright claims. But Wright’s response to Wells is that difference is not necessarily a sign of distance, but rather can be seen as “the result of intentional transformation of the source text.”30 This means that although there are superficial differences between the two laws, Wright believes that those differences are the evidence of the Covenant Code adapting the Hammurabi Law to fit its own culture.

Instead of the Covenant Code adapting the Law Code of Hammurabi, Davies has proposed that many of the laws in both codes are the product of basic Middle Eastern cultural ideologies.31 This means that because the two different kingdoms have the same basic human needs and a similar cultural philosophy, they would naturally create similar laws without any influence one to another. Davies goes on to state that it is entirely probable there is an ancient advanced law that has influenced both codes. The idea is that this code originated in the ages before the Semitic tribes separated, and some tribes after separation carried on many of the fundamental principles of the original law. This view is quite sustainable considering that the Law Code of Hammurabi is itself evidence of much older legal edicts.

A final look at the question of the relationship between the Covenant Code and the Law Code of Hammurabi, Sam Jackson, in a paper presented at the Society of Biblical Literature Conference in 2008,32 argues that the biblical text uses historical events to motivate obedience to God’s laws. He states that of all the ancient near-eastern legal collections, only the Edict of Telipinu, a Hittite code dated to around 1500 B.C., uses this method. This is used to support Weeks’ theory that rather than borrowing a treaty form from other nations, the Covenant Code conforms to a standard Israelite historiography form of writing.33

Conclusion

The Law Code of Hammurabi is one of the oldest pieces of Mesopotamian literature and it has given scholars insight into the nature and psychology of law in ancient Babylonia. The law code itself has enabled historians to extend further back into history the role of law in a society, through comparisons with other similar ancient codes and Mesopotamian kings. It is clear that although the Law Code of Hammurabi is not the first legal precept to be adopted by a community, it is certainly the oldest compilation of a collection of laws. Its barbaric philosophy of eye-for-eye may seem harsh to western thinkers, but it does contain glimpses of what many would consider common-sense law.

Although the influence of the Law Code of Hammurabi on the Hebrew Bible is debated, there is no denying its impact on advancing our knowledge of the ancient world in which it operate.

Endnotes

- Wieacker 1981: 281.

- Mieroop, M. V. (2005). King Hammurabi of Babylon. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing: 1.

- Ibid. p 3.

- Ibid. p 81.

- Ibid. p 1.

- Vincent, G. E. (1904). “The Laws of Hammurabi.” The American Journal of Sociology vol IX: 738.

- Mieroop: 3.

- Ibid. p 12.

- Ibid. p 79.

- Ibid. p 82.

- Ibid. p 80.

- Slanski, K. E. (2012). “The Law of Hammurabi and Its Audience.” Yale Journal of Law & the Humanities vol 24:97: 105, 6.

- Ibid. p. 103.

- 14. Mieroop: 100.

- 15. Ibid. p 101.

- 16. Slanski 2012: 97.

- 17. Ibid. p 97.

- 18. Ibid. p 107.

- 19. Slanski 2012: 108.

- Davies, W. W. (1905). The Codes of Hammurabi and Moses. Cincinnati: Jennings and Graham: 13.

- Ibid. p 23.

- 22. Ibid. p 23, 24.

- Slanski 2012: 105.

- Ibid. p 105.

- McNeil, D. G. (1967). “The Code of Hammurabi.” American Bar Association Journal, vol 53, No.5: 445.

- Vincent 1904: 748.

- Ibid. p 739.

- Mieroop 2005: 109.

- Ibid. p 109.

- Wright, D. P. (2006). “The Laws of Hammurabi and the Covenant Code: A Response to Bruce Wells.” Journal for the Study of the Northwestern Semitic Languages and Literatures: 212.

- Davies 1905: 9.

- Jackson 2008: 2.

- Ibid. p 2, 3.