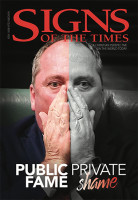

In our theatres, on our TV sets and throughout the political arena, a battle rages between the “public” and the “private”. How accountable are those who tread the world’s stage to those who enjoy their performances? Don’t even our most public figures have the right to some private space? A reasonable question … unless the divide between the public and the private happens to be a convenient fiction.

Hollywood is no stranger to the public-private debate. We recently saw the release of The Wife, a provocative film starring Glenn Close as Joan Castleman, the dependable wife of a celebrated American novelist. Based on the best-selling book by Meg Wolitzer, it tells the story of a couple whose public and private lives are worlds apart. The story opens aboard a jet winging its way towards Helsinki, where Joan’s husband will receive a Nobel Prize for Literature. However, she is reflecting on the rotten core of an outwardly perfect marriage: “The moment I decided to leave him, the moment I thought, enough, we were 35,000 feet above the ocean, hurtling forward but giving the illusion of stillness and tranquility. Just like our marriage.”1

A couple of months prior, the cinemas were playing host to another production about just this sort of illusion. Chappaquiddick chronicled the closer-to-real-life tale of Senator Ted Kennedy’s traumas in 1969. The youngest brother of the by-then deceased JFK drove his car off a one-lane bridge and into a tidal channel. The married senator was able to swim free, but not his 28-year-old passenger, Mary Jo Kopechne, who was trapped. Instead of reporting the accident, Kennedy returned to his hotel, traumatised and overwhelmed with worry about the impact of the crash on his potential presidential campaign. While he called friends and family for advice on how to preserve his public image, Kopechne suffocated in the vehicle.

In real life

Of course, The Wife and Chappaquiddick are largely fictional works, but Hollywood has had to deal with many factual public–private divides over the past 12 months. At the beginning of 2017 uber-producer Harvey Weinstein occupied an exalted position in American entertainment. Publicly, he was the executive producer on a wide range of cinematic blockbusters, from Gangs of New York and The King’s Speech, to Paddington and Pulp Fiction. His success earned him a slew of awards, as well as a reputation for a “Midas touch”. Actors’ careers would soar or fall, according to his interest. Yet alongside his success story was a growing reputation for temper tantrums and vindictiveness. “I’m a benevolent dictator,” Weinstein is reputed to have said. When it became clear that in private, his dictatorship involved threatening actresses with doom if they didn’t supply sexual favours, the gilded gleam definitely came off.

The private revelations that followed precipitated Weinstein’s public fall from grace, and many more luminaries soon traced his downward trajectory. Actor Kevin Spacey, comedian Louis CK and director Brett Ratner all suffered serious career setbacks. The mountain of allegations that overwhelmed them suggested there was no place in the public eye for those who could not behave themselves in private. Yet it seems that in both America and in Australia, we hold other public figures to a different standard.

Politicians on both sides of the Pacific have held for the longest time that they have the right to separate their public and private lives. Netflix’s political commentary show, The Circus, touched on this while reporting on the Trump/Clinton presidential race. In October 2016, multiple women came forward with allegations of sexual misconduct against Donald Trump. However, American voters were divided over the reporting of his behaviour. One woman defiantly told The Circus, “I’m not electing the Pope!” and maintained that what Trump did in private was his affair and his alone.

Australia has had to cope with sensitive revelations of its own recently when news broke regarding the Deputy Prime Minister and National Party leader Barnaby Joyce. Though married, he had conceived a child with a staff member. Joyce was forced to resign his positions in disgrace, but the weeks that led up to that decision were filled with social commentators wringing their hands over what parts of the scandal were public and which should remain private. Not surprisingly, the majority of our elected representatives were very careful about which stones they threw. I’m sure there are more than a few glass houses in Australia’s capital.

It’s not hard to appreciate how politicians can object to the glare of the media spotlight on their private lives, especially when it concerns family members who have not deliberately placed themselves in the public sphere.

Joyce’s own plea for privacy was constantly tied to the effect it would have on his wife and four daughters: “It’s a private matter, and I don’t think it helps me, I don’t think it helps my family, I don’t think it helps anybody in the future for us to start making this part of a public discussion.”2

It was a line repeated across the media, by Joyce’s defenders and detractors. Yet this refusal to connect the public with the private began to sound all too convenient when questions surfaced concerning the length of the affair between Joyce and his lover, and whether or not it had affected his judgement as a minister, particularly her appointment to high-paying parliamentary staff positions. Yes, it was reasonable for Joyce to ask for privacy for the sake of his family, whose suffering was being brought about through no fault of their own. But it is another thing entirely to suggest that there is no link between his public and private lives.

Then Joyce really shot himself in the foot when he and his new partner agreed to a handsomely paid “tell-all” Channel 7 interview. Suddenly all his previous protestations sounded hollow and his judgement was once more under question.

Connecting the dots

What if our public actions are actually spurred on by our private thoughts? Wouldn’t it then be more just to judge them together? Eighteenth century French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau suggested morality was a burden imposed by the state, and that caring what others think is one of the fundamental evils of modern society. It’s a sentiment that’s echoed in the West today.

But does knowing anything about Rousseau’s private life affect the validity of his views? He said a person should refuse to acknowledge any judgement of their actions except “. . . that we ourselves pass on them.”3 But this is a very convenient position for a man who sent every one of his five children to the Paris Foundling Hospital immediately after their births. Is there really no connection here between his public opinions and private actions?

Rousseau is just one of a number of celebrated thinkers whose teachings on topics like sexuality, education and marriage might bear reconsidering when their private lives are taken into account. But should this really be a surprise? Seventeen hundred years before Rousseau, Jesus was teaching His followers there was an inescapable link between the public and the private.

The morality debates of first-century Palestine were not that different to those playing out in the media today. The Pharisees, a conservative religious and political force, were very much about keeping the public and private divided. They dressed, prayed and behaved in a way that courted the best possible public opinion. But their private practices regularly drew Jesus’ condemnation. He called them “whitewashed” for their loophole-focused financial dealings, and “hypocrites” for the way they neglected their parents. Jesus felt comfortable in doing so because He saw no divide between the public and the private. He told the crowds that all actions, in all spheres of life, proceed from the one source: “The things that come out of a person’s mouth come from the heart, and these defile them. For out of the heart come evil thoughts—murder, adultery, sexual immorality, theft, false testimony, slander. These are what defile a person . . . ” (Matthew 15:18, 19).

According to Jesus, it makes perfect sense to be wary of trusting a politician to keep their public promises, if they cannot keep those they have made in their private life, because all of their decisions come from the same heart. If a person is selfish in private life, why wouldn’t the same heart lead them to make self-serving decisions in public life?

The public-private divide is a fiction that we maintain because we want to downplay the seriousness of the moral challenge we face. We tell ourselves we can turn “good” and “bad” on and off in our lives like hot and cold taps. But Jesus’ response is the devastatingly accurate analogy, “Do people pick grapes from thorn bushes, or figs from thistles? Likewise, every good tree bears good fruit, but a bad tree bears bad fruit” (Matthew 7:16, 17).

So what is the answer—only elect politicians who have never done anything wrong? That would certainly lead to a very quiet parliament! No, the Bible’s clear that every person has a fundamental and heart-deep brokenness. Pretending that the problem is neatly contained in just one part of our life is ludicrous. Trying to change your heart from the inside out, without help, while pretending there is nothing wrong, is just as silly. Yet Jesus said that there’s a solution that fits the politician as well as the voter: “With man this is impossible, but with God all things are possible” (Matthew 19:26).

1. M. Wolitzer, The Wife, Scribner, 2004.

2. The 7:30 Report, February 7, 2018, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-02-07/barnaby-joyce-speaks-about-new-relationship/9406352

3. D. Potts, “Were Rousseau’s children victims of his moral theory?”, Policy of Truth, https://irfankhawajaphilosopher.com/2015/06/28/were-rousseaus-children-victims-of-his-moral-theory/