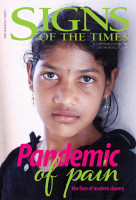

Papua New Guinea (PNG) is a beautiful country, often described as the “land of the unexpected”. Its coastal strolls, endless greenery and flashes of colour; its fascinating cultures leave visitors in awe.

And yet PNG is one of the most dangerous places on earth, especially for women, with more than two-thirds of women having experienced physical or sexual violence. Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) goes so far as to say that domestic and sexual violence is a medical humanitarian emergency in PNG, with levels of gender violence normally only experienced in war zones.1

This abysmal situation is aggravated further by a severe lack of emergency accommodation and counselling services. It’s a situation that eight students from the Avondale College of Higher Education (NSW) decided to do something about, partnering with ADRA Australia and other Seventh-day Adventist Church agencies [publishers of Signs of the Times] to provide real solutions. Linda Ciric and her Poverty Development studies classmates, all first year students, are partnering with key groups within the denomination to raise funds for and awareness about the issue of family violence in PNG.

“We wanted to get the message out that this is happening, and it isn’t right,” explains Ciric. “As Christians, we can help. Our project slogan is They are not alone and we want them to know that.”

Says classmate Jessica Krause, “We’ve reached out to ADRA Australia, women’s ministries groups within the Adventist Church, as well as individual congregations, to see how they can help with fundraising and awareness.”

The students are being guided by their lecturer, Dr Brad Watson, who recently spent time in PNG compiling a report on family violence for the Church’s South Pacific regional office. His revelations are confronting.

“What we’re seeing are some of the highest rates of gender violence in the world, but the Church [in PNG] generally doesn’t have any counselling skills,” Watson says. “There is also no formal refuge program for women; only a few of the mainland churches have their own women’s refuge.”

As a result, the students set themselves a fundraising target of $A100,000, hoping to support a refuge centre providing accommodation and counselling. And, with the support of ADRA Australia, they’re well on the way to reaching their goal.

“ADRA is committed to addressing gender-based violence in PNG, so we’re excited by the passion of Avondale students who are fundraising for this cause,” says ADRA Australia CEO Mark Webster. “We will extend our work in this area by establishing basic counselling facilities and safe houses in local mission headquarters to better support women and children, and hope to work with the [Adventist Church’s] Family and Women’s Ministries departments to empower and inspire churches across Australia to fundraise and advocate for women in PNG so they know they are not alone.”

Something that began life as merely a compulsory class assessment turned into a project of passion as the students began to truly comprehend the tragic realities.

“I’ve been to PNG a couple of times and I’ve fallen in love with the country and the people there,” says student Kim Parmenter. “Just knowing that these are the sorts of issues they face and knowing that we’re not really doing quite enough about it makes me want to do something more.”

Fellow student Yannick Coutet agrees, saying the turning point for him came from viewing Russian photojournalist Vlad Sokhin’s work Crying Meri.2

“Seeing pictures on Google—they used to be just pictures,” he explains. “But it wasn’t until I read about the issues and saw pictures of how some women were being treated that it touched me, motivating me to help. It’s really sad, but it’s really impacting—and that’s why we’re taking action.”

It’s scenarios like these that are all too familiar for ADRA Australia’s PNG project officer Ellen Hau Pati, who grew up in the Gulf Province and has lived in Port Moresby for the past 20 years.

“In the community, I would see almost every day a woman with a black eye or hear a woman screaming for help,” recalls Hau Pati. “It’s common. I’m one of the lucky ones—I personally haven’t experienced it. I came from a home where my parents never physically abused each other and I married a man who isn’t violent, but I’d say with certainty that mine is a rare case.”

Given the facts, statistics and personal narratives, the question is, how has gender-based violence in PNG reached this level? Hau Pati gives several reasons, including poverty and a weak justice system—there is no real law enforcement, especially in the more remote villages. But with more than 800 languages in PNG and just as many cultural groups, she says the biggest cause is the fragmentation of traditional cultures through modern urbanisation.

“In the past, we had a social network with rules and taboos that controlled us,” she says. “But now people have moved to the cities and married between different villages. When people intermarry, rules and sanctions from their original communities don’t apply anymore, and men feel as though they can get away with more.

“The family culture is still strong in PNG, but a lot of that has broken down because of the movement and mixes within communities. If you get married within your village there is a good chance your family can step in and help [if there’s violence]. But in the towns and cities, it’s really difficult; everyone is living away from their tribal network.” But, she says, “Slowly, people are starting to accept that it’s not just a domestic issue. I’m grateful to the Avondale students for addressing this issue. There’s a lot of opportunity for us to do more, and I believe this is our gospel calling.”

1. https://www.msf.org.au/papua-new-guinea

2. “Meri” is Tok Pisin (PNG pidgin English) for “woman.” To view Sokhin’s work, visit http://www.vladsokhin.com/work/crying-meri/