My father was my hero. I suppose it’s that way for many boys. But in my case, I thought I had a little more reason for his exalted status in my mind.

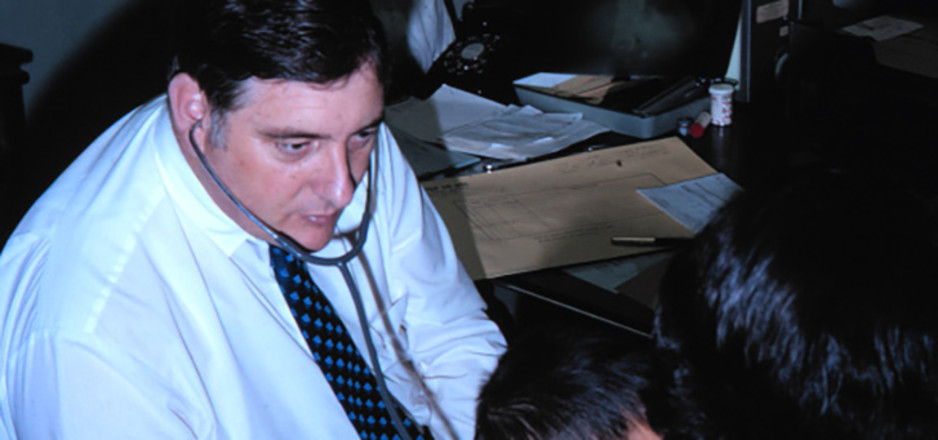

He was smart. Really smart. The smartest person I’ve ever met. And I’ve met plenty of smart people. From humble roots, he made it to the pinnacle of his medical profession. And so much more.

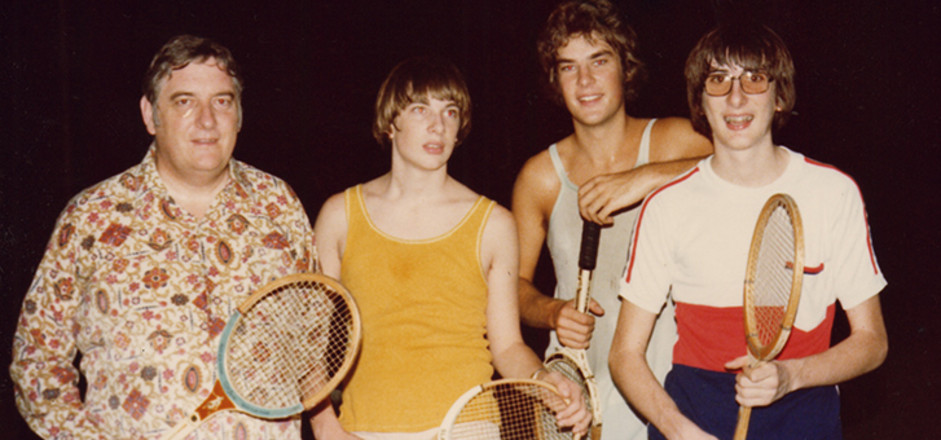

He was interesting. The most interesting person I've ever met, and I’ve met lots of interesting people. His passions ranged from medicine and theology, from the theory of numbers to geography. He was obsessed with the Olympics, cricket and tennis, and could recite with encyclopedic accuracy who won what, where and when. As long as the winner was Australian.

He had the most life in him of anyone I’ve ever met. And you know what’s coming—I’ve met plenty of lively people.

But there was something more about him I admired.

When everyone else was fleeing Saigon in the midst of the Vietnam War, my father flew in. He worked tirelessly treating civilians wounded in the vicious conflict. When he arrived home in Malaysia he presented his boys with, among other things, a bullet. But it wasn’t like any bullet I’d seen before. It was a bullet head smashed into something unrecognisable. “I extracted this from a woman’s leg,” he said. “It shattered her bone but she’s going to be OK.”

Many years later I visited Vietnam as part of a US Government delegation. On Sabbath I attended Saigon Adventist Church. After the service a woman approached me quietly and simply said, “your father saved my life”. She’s hardly alone. He saved lives everywhere he went. He never cared about money, fame or honours. He cared about people.

In the early '70s my father took another trip, this time to war-torn Laos. From the capital, Vientiane, he decided to travel to another town in a mini-van with some American medical professionals. It was, I suppose, just another day in the life of a medical missionary in a conflict zone.

At the time Laos was a sparsely populated place so within a few minutes of leaving, they were driving through a rural landscape. “How safe is the road?” my father asked his American friends. “This is the main road, it’s secured. We never have problems here,” they replied.

Like any trip, the friends fell into conversation as the kilometres clicked by. All was well, until they drove around a corner. There, right across the main highway, was a barricade. And manning the barricade were Communist guerillas. The narrow road prevented them from turning around. Even if they could, all guns were trained on their mini-van—they would never escape with their lives.

The commander approached the driver’s window and, in rudimentary English, demanded “show me you passport!” The driver was dumbstruck by fear. “I said, show me your passport!” the commander screamed. The driver, in panic, mumbled an indecipherable response. The commander stuck his gun in the window and roughly queried, “don’t you speak English?” The American driver mustered his nerves enough to mumble, “I don’t have my passport . . . I can. I can go back, um, to Vientiane and, ah, get it . . .”

This did nothing to placate the commander, who put his finger on the trigger and the gun to the driver’s temple, and once again screamed, “show me your passport!”

My dad could see bad things were about to happen. And in the extremity of distress he blurted out, “I’ve got my passport.” Immediately he regretted it. The cold gun barrel left the driver’s temple and was jabbed into his face. He slowly reached into his pocket and presented the gunman with his passport. “What will happen to us if he steals it?” he thought. Then he realised, “What am I thinking? Losing my passport is the least of our problems. Lord, help me!”

The commander snatched the passport and stared at the cover. He’d expected to see a screaming eagle. Instead he was confronted with a happy kangaroo and his emu buddy. The commander looked up and in a confused tone said, “You’re Australian?.” He’d gone from shouting to a soft query. My dad saw the metamorphosis, perceived the unexpected difference, and happily responded, “Yes, Australian!” The commander stood back and waved them on with the final words, “You OK, sir, you go.”

They drove around the corner and stopped. The little group of medicos bowed their heads and prayed the most sincere prayer of thanks to our God imaginable. Providence had ensured the driver didn’t have his passport. If he had, they would have assumed they were all Americans and everyone would have been murdered.

How can I say for certain? Tragically, just a few weeks later, an Australian diplomat’s daughter was caught up in a similar ambush. She didn’t have her passport. She was slaughtered.

I grew up on this story. Always thinking just how fortunate I was that God had saved my dad so I didn’t have to grow up fatherless and hero-less.

Fast-forward 33 years and I was driving with my dad through the streets of Washington, DC. Thinking about life, he turned to me and said, “You know, James, people think you get old and you don’t want to live anymore. But I want to live more now than I ever have!” He said it with the kind of power that lodged his words in my mind.

Not long after, he travelled to the rural Victorian town of Mildura. He was met by a friend. After leaving the airport, they came to an intersection. They rolled out into the middle just as a station wagon came flying across in the other direction. If you tried to choreograph the collision you couldn’t. One car travelling, say at 60km/h, the other at 100km/h—four metres of car to hit—a little over two metres to collide with the passenger compartment. A tiny fraction of a second of time when both cars would be in precisely the same place.

Bam! And my father was dead.

God didn’t have to do a great miracle. All He had to do was make the plane a tiny fraction of a second later. He could have held up the bags for a moment. A problem getting on the seat belt would have delayed the trip enough to avoid catastrophe. Almost any infinitesimal divine intervention and my father would have gone on with the day happily.

God worked a spectacular intervention to save my father in a war zone. Why couldn’t He work a simple one to save him in peaceful rural Victoria?

When a family member was called with the awful news, he exclaimed, “Where were the angels?”

Good question! Where were they? Why didn’t they protect him? What about the promises? What about every children’s story ever told in every church on every Sabbath? Where was the miracle?

Even his enemies viewed my father as a sincere Christian. He’d given his life in service. He began every day with prayer and Bible studies. He kept the commandments and had the faith of Jesus. He’d kept up his side of the bargain. Where was God?

Sure, we’ll see each other again. But in heaven I won’t need the wisdom and compassion of an earthly father. I need him here, now. And what about my kids? The only memories of their grandfather will be the occasional anecdote I pass on when I talk about him. Which isn’t too often. Because it makes me sad.

How to reconcile it all? Amazing miracles. Mundane tragedy. Striking divine intervention. Stony heavenly silence. Angels here and now. Now where are the angels?

This is what I know. Yes, the Hebrew worthies were saved from the fiery furnace. But we believe Isaiah was sawn in half. Yes, David defeated Goliath. But he couldn’t save his own sons. Yes, Paul and Silas were miraculously freed from prison. But John the Baptist rotted in Herod’s prison with no miracle for him. Yes, Christ will come with power and glory. But Jesus was spat on and nailed to a cross where He cried out to a Father He believed had forsaken Him.

The story of the life of the godly in a sinful world is not one of temporal deliverance. Even Lazarus got old and died. Ultimately, in this world, there are no permanent miracles.

But our miracle stories are important, just not for the reasons we often emphasise. Because, ultimately, no miracle gives us eternal health in a world bathed in sin. And no matter how hard we pray, or how faithfully we believe, God gives us no guarantees. The race doesn’t always go to the swift. The battle to the strong. And miracles do not always come to the faithful.

So why do miracles at all? To achieve God’s will? Maybe. But it’s not God’s will that there’s sin. Death. Suffering. Or pain at all. So how does the occasional spectacular intervention come close to achieving God’s perfect purpose in a world awash with acts that violate it? Miracles don’t mean a sinful world operates according to God’s purpose. They do do something, however. They point to the only unequivocal promise we do have: salvation by faith. Not in this world but from this world.

As good as life can be, as happy and fulfilling, as grand and exciting, we are still trapped in a cycle of human tragedy, the sum total of which is so immense that no scale yet devised can measure its weight. The miracle stories we tell ourselves are footnotes to the overarching human narrative of utter, heartbreaking tragedy. The promise of salvation? That is indeed THE miracle story; the capstone of human history; the promise of all promises, paid for in our Lord’s blood, and sealed with His love.

So where were the angels? The same place they always were. And where are they now? Watching over my dad’s resting place for the day when God performs the miracle that will wash away all miracles. When God keeps the greatest of all promises. When finally the cycles of hopes, disappointments, victories and tragedies are replaced by a wholeness of pure love. Maybe that’s the children’s story we should tell more often. And leave the minor miracle stories where they belong—as little glimpses of the fulfilment of the ultimate promise.