Solomon said in Ecclesiastes 7:18: "Whoever fears God will avoid all extremes."2 Every denomination has extremists and Seventh-day Adventist Church pioneer Ellen White continually warned against fanaticism.3 However, can Adventists learn from an extreme form of Christianity—monasticism—with its mandatory poverty, chastity, fasting, silence, hairshirts, reed beds, midnight vigils and self-flagellations?

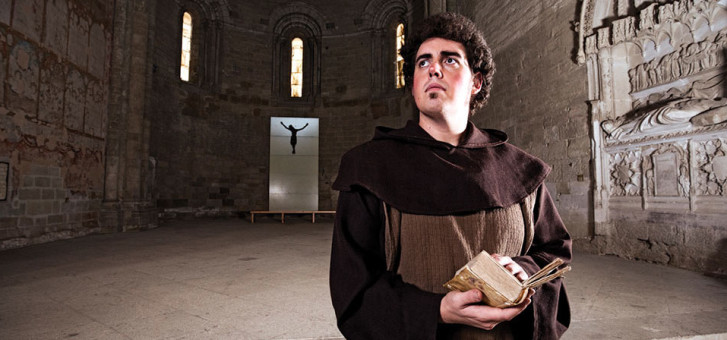

Monk up a pole: the origins of monasticism

Monasticism, as we know it, arose in fourth-century Egypt with Anthony the Great and Pachomius.4 Treating the human body as intrinsically evil, these men strove to live isolated lives with little food, sleep, companionship or recreation.5

Famous Dark Ages monastics included: Isidora, who pretended to be mad, wore an old dishrag and ate nothing but crumbs;6 Catherine of Siena, whose diet consisted of communion wafers and pus from the sores of the sick;7 and Simeon Stylites, who lived for 37 years atop an 84-foot pole!8

Nazirite oath: the biblical model of seclusion

There are, of course, biblical examples of people living apart from others for a time. Numbers 6:1-21 prescribes the oath of the Nazirite, whereby a person vows to abstain from grape products, cutting their hair or touching a corpse. Famous Nazirites included Samson, Moses, Elijah, John the Baptist,9 Paul10 and probably even Jesus.11

These biblical Nazirites did withdraw for a time for prayer, fasting, silence and contemplation. However, they always returned to serve their communities. What was radically new about fourth-century monasticism was the idea of permanent isolation and total aversion to the material world—especially the human body.

Gnosticism: monasticism’s dark origins

Monasticism is actually rooted in the first major Christian heresy: Gnosticism. Gnosticism was an umbrella term for certain Eastern pagan beliefs mixed with Greek philosophy, especially Platonism with its emphasis on the immortal soul.12 When Emperor Constantine converted to Christianity in 312 AD, Christianity began a process of accommodation with the pagan majority. This involved adopting some elements of Gnosticism.

Gnosticism, however, turns the Bible on its head. It views the Hebrew Creator of Genesis as an evil or lesser god (called the Demiurge), with creation a flawed mistake.13 The serpent is not evil but good, come to liberate Adam and Eve from their golden-caged prison in Eden.14

During the New Testament period, this heresy led to viewing the human body as either inherently sinful or as an irrelevant shell for an immortal soul, and subsequently to the extremes15 of liberal Libertinism (such as Christians visiting prostitutes)16 and conservative asceticism (such as mandatory celibacy and fasting).17 Paul had to battle both of these ideas.

Similarly, because of this negative view of the human body, Gnostic-Christians taught that Jesus had only come in spirit form (known as docetism).18 This prompted the apostle John to describe anyone who denied Jesus had come in the flesh as an anti-Christ.19

The early church ultimately suppressed Gnosticism. However, according to today’s Gnostics:

"Orthodox Christianity clashed with Gnosticism and the church fathers read Gnostic texts in order to refute them. This led indirectly to Christianity absorbing a certain amount of influence from Gnosticism."20

Enter the matrix: Gnosticism’s impact

The impact of Gnosticism on Christianity cannot be understated, given the New Testament canon was largely selected in reaction to it.21 As acknowledged by famous German theologian Jürgen Moltmann:

"In the degree to which Christianity cut itself off from its Hebrew roots and acquired Hellenistic and Roman form, it lost its eschatological hope and surrendered its apocalyptic alternative to 'this world' of violence and death. It merged into late antiquity’s Gnostic religion of redemption. From Justin onwards, most Fathers revered Plato as a 'Christian before Christ' and extolled his feeling for the divine transcendence and for the values of the spiritual world. God’s eternity now took the place of God’s future, heaven replaced the coming kingdom, the spirit that redeems the soul from the body supplanted the Spirit as 'the well of life', the immortality of the soul displaced the resurrection of the body, and the yearning for another world became a substitute for changing this one."22

In other words, Gnosticism corrupted Christianity’s original Jewish message about redemption of this world through a Saviour, into a Greek message about escape for our supposed immortal souls from this world. In doing so, it turned creation itself into sin, contrary to Paul’s teaching that creation groans to be freed from sin.23

These concepts spread into monasticism and from there into many "mainstream" Christian denominations. We even see Gnosticism’s legacy in popular culture, such as the movies Tron: Legacy and The Matrix, which are essentially Gnostic parables.24

Wholism: the balanced Adventist approach

The Adventist Church is arguably the most anti-Gnostic of today’s Christian religions. In direct opposition to Gnosticism’s bleak view, we affirm the Genesis account of a good God making a very good creation.25 We acknowledge this weekly in the Sabbath.26

Through our views about the nature of man and state of the dead, we affirm the human body was made in the very image of God, unified in one indivisible entity.27 In our health message, we affirm eating, drinking, rest and sex as being part of God’s original plan for humankind.28 While the Fall corrupted those functions, our bodies are not intrinsically evil, but rather, the temples of the Holy Spirit.29

In our end-time beliefs, we don’t seek a ghost-like escape from this world.30 Instead, we believe in a physical resurrection,31 a physical second coming,32 a final destruction of the wicked33 and a physical recreated New Earth.34

These Adventist "distinctives" are often described together using the term "wholism". Wholism is considered by some to be Adventism’s most important contribution to Christianity.35

Wholism is a very positive way to describe our remnant message,36 separating as it does original Christianity from the pagan philosophies of "Babylon". Adventists should make terrible monks because we reject their theology, rooted in Gnosticism’s fear of the created world and hang-ups about the human body. Instead, we embrace a wholistic faith that acknowledges both creation and Creator as originally good. Thus, far from being fanatics, Adventists are (or should be) the most balanced Christians in the world!

- This article largely credits Jack W. Provonsha’s excellent piece about wholism and the origins of monasticism in “And God Saw it was Good”, from God is with Us (Hagerstown MD: Review & Herald Pub., 1968).

- All texts are from the New International Version.

- Ellen G. White, “Fanaticism and Extremism”, Evangelism (Hagerstown MD: Review and Herald Pub., 1964), 610-613.

- E. A. Livingstone, Oxford Concise Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford: Oxford Uni. Press., 2006), 392.

- Ibid.

- “Saint Isidora, the Fool for Christ”, The Nuns’ Garden: The website of the Sister of Saint Syncletike, http://thenunsgarden.org/, retrieved Mar 31, 2014.

- E. Gardner, “St. Catherine of Siena”, The Catholic Encyclopedia (New York: Robert Appleton Company), Retrieved March 31, 2014.

- H. Thurston, “St. Simeon Stylites the Elder”, The Catholic Encyclopedia (New York: Robert Appleton Company), Retrieved March 31, 2014.

- The clearest NT example of the Nazirite oath, where the angel states John will drink neither wine nor strong drink (Luke 1:13-15), and where baptism itself is inherent in the Nazirite vow.

- Paul is especially interesting, with a veiled reference to cutting his hair for an oath (Acts 18:18).

- Especially during the last part of His ministry, as He prepared for death. The parallel between the oath of the Nazirite and Jesus’ hometown of Nazareth hasn’t been lost on scholars. Nor has the fact Jesus personally refused to drink wine at the Last Supper (Mark 14:22-25).

- F. Cross, “Platonism”, The Oxford dictionary of the Christian Church (New York: Oxford Uni. Press., 2005).

- John Arendzen, "Gnosticism" The Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol. 6 (New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1909), retrieved 31 July 2013 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/06592a.htm>.

- Andrew Smith, The Gnostics (London: Watkins Pub., 2008), 188.

- D. Dunn, The New Testament: History, Literature and Social Context, 4th Ed. (Belmont CA: Wadsworth, 2003), 27,32-33.

- 1 Cor. 6:12-20.

- 1 Tim. 4:1-3; Col. 2:16-20; Rom. 14:1-3.

- E. A. Livingstone, n4, 176, 244.

- 1 John 4:1-3; 2 John 1:7.

- Andrew Smith, Gnostic Writings on the Soul (Woodstock VT: Sky Light Pub., 2007), xvii.

- The NT canon was formed in opposition to Gnostic-Christian Marcion of Sinope who, viewing the Hebrew Creator as evil, produced his own version of the Bible without an OT and only a heavily edited version of Luke: Dunn, n16, 57, 557.

- J. Moltmann, The Spirit of Life: A Universal Affirmation (London: SCM Press, 1992), 89.

- Rom. 8:18-22.

- Grant Morrison, Supergods: Our World in the Age of the Superhero (London: Roman House, 2011), 315.

- See especially SDA Fundamental Belief #6 “Creation”; Gen. 1:31 and Gen. 2:2.

- See especially SDA Fundamental Belief #20 “The Sabbath”; Ex. 20:8-11.

- See especially SDA Fundamental Belief #7 “Nature of Man”; Gen. 1:26,27; Ex. 33:20, 1 Tim. 6:16; Eccl. 9:5,6 and Ps. 146:3,4.

- See especially SDA Fundamental Belief #23 “Marriage and Family”; Gen. 2:18-25.

- See especially SDA Fundamental Belief #22 “Christian Behaviour”; 1 Cor. 6:12-20; 1 Cor. 10:31 and 1 Tim. 4:1-5.

- Which it could be said is exactly what modern evangelical teachings about the Rapture do. Thus, the Rapture to some extent is arguably an extension of teachings about the immortal soul.

- See especially SDA Fundamental Belief #26 “Death and Resurrection”; John 11:11-14.

- See especially SDA Fundamental Belief #25 “Second Coming of Christ”; 1 Thes. 4:13-18.

- See especially SDA Fundamental Belief #27 “The Millennium and End of Sin”; Rev. 21:1-15.

- See especially SDA Fundamental Belief #28 “The New Earth”; Rev. 22:1-5.

- According to a 1987 survey, 36 per cent of professional Adventist theologians surveyed viewed wholism as more important than eschatology, the Sabbath, the great controversy theme or the sanctuary message: Malcolm Bull and Keith Lockhart, The Intellectual World of Adventist Theologians (October 1987), republished in Spectrum Magazine, retrieved <http://spectrummagazine.org/files/archive/archive16-20/18-1bull.pdf>

- Rev. 14:6-12.

Stephen Ferguson is a lawyer from Perth, Western Australia, and member of Livingston Adventist church.