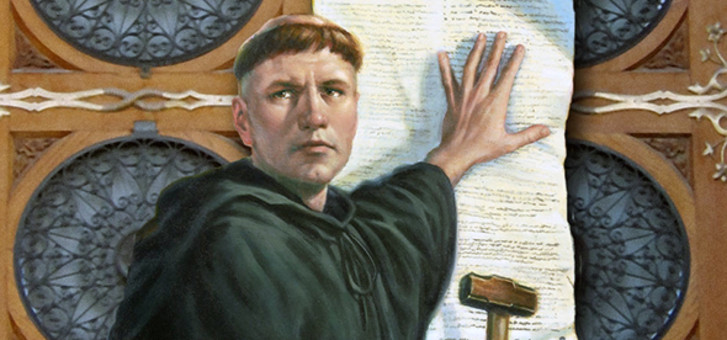

You are reading this on our anniversary. No, not our anniversary in the sense of you and me. Though I’m flattered you’d consider the idea. But on the anniversary of the way we think, the way we pray, the way we understand what Christ has done for us. Today, October 31st, is the anniversary of when Martin Luther nailed his 95 theses to the Schlosskirche in Wittenberg, Germany.

Or did he? Some historians now believe he did nothing of the sort. But the weight of opinion falls in favour of the nailing and Ellen White backs it up in Great Controversy. Either way, as the 95 theses were written in Latin, only the scholarly class could read them initially. It was a year later, when they were translated, printed and distributed all over Europe, that they became the earthshaking phenomenon we know today.

The theses are not, as I imagined, a set of carefully crafted propositions leading to an irresistible conclusion. Rather, they are a set of densely phrased propositions framed in rhetorical questions that become increasingly sharp as they progress. The theses are designed to begin a conversation, not end one.

They succeeded most spectacularly in their goal. Indeed, they started a conversation that eventually split the church and triggered a religious and intellectual revolution, from which the echoes can still be heard today. So what are these 95 revolutionary thoughts?

The theses focus on the six Ps: the pope, purgatory, pardons, the poor and personal piety.

Luther takes repeated stabs at defining the appropriate limits of the pope’s authority. For example, in thesis 6, he explains the pope can’t “remit any guilt, except by declaring that it has been remitted by God and by assenting to God’s remission . . .” See the balance there? He doesn’t dismiss the pope’s authority, he just clarifies the limits to it. Similarly in 26, he clarifies the pope can only assist souls in purgatory through intercession to God, not by freeing them through his own power.

Luther makes his loyalty to the Catholic Church clear in 7, where he states that God only remits the sins of those who He also brings “into subjection to His vicar, the priest”. Similarly, he excuses Catholic leadership, noting that the corrupt priests’ tares were sown “while the bishops slept”. The theses are not an attack on the Catholic Church, per se, its core doctrines or its authority. Luther merely addresses particular abuses that he repeatedly credits to low-level actors. Though, near the end, he does directly question the pope’s decision to use revenue from indulgences to build St Peter’s Basilica. Maybe his diplomatic patience waned as his writing progressed?

He focuses much attention on purgatory—the place where Catholics believe people who die in Christ’s grace, but who are not fully sanctified, can suffer a little and thereby be made holy enough to enter heaven. Luther doesn’t quibble with this doctrine, only that anyone’s suffering can be alleviated by the purchase of indulgences.

We think of Luther as being all about grace but his concern in part was that the sale of indulgences and pardons was letting people off far too lightly. In thesis 40, he notes “True contrition seeks and loves penalties . . .” and, in 42, he warns that pardons are dangerous as they might be preferred to performing other, more difficult, good works.

My favourite thesis is 45: “Christians are to be taught that he who sees a man in need and passes him by, and gives [his money] for pardons, purchases not the indulgences of the pope but the indignation of God.” In this, Luther is correct. But maybe not for the reason he believed.

Although Luther’s 95 theses are far from what we understand as Protestantism today, they contain the principles that would subsequently flower: the pope is only right when he acts in accordance with God’s will; the centre of the church is God’s grace and the cross of Christ (eg. theses 62 and 93); and true religion involves helping the least fortunate, not building elaborate edifices (45 and 82).

After reading Luther’s theses, I ask myself what errors of understanding or practice mar our Christian walk today? If someone were to tape a list of our faults on the front door of our church or, even worse, on our own front door, how many would there be? Please let it be less than 95! We know how the pope responded to Luther’s theses. I wonder how we would respond to a list of our faults.