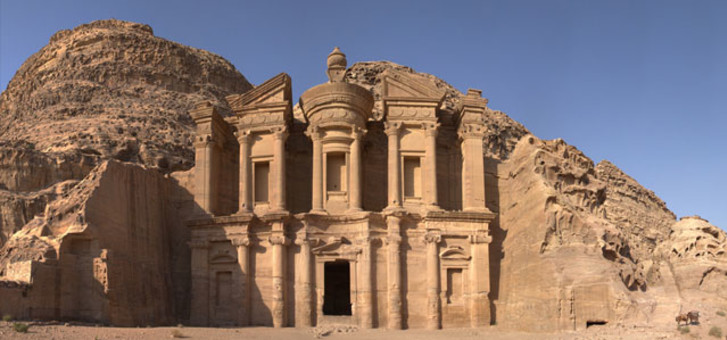

A few of its silent tombs were occupied by roving Bedouin, but otherwise it was uninhabited. Even when the Jordanian government opened its gates to tourism Petra still seemed hot and dreary. There were tombs and temples aplenty but there seemed to be no sign of life.

It was not only the casual tourists who got that impression. Some scholars even suggested that it had not been a residential city. There were few signs of houses and occupation, so perhaps it had just been a pilgrim city where Nabataeans came to worship or be buried.

Now all that has changed. Over the last ten years there has been intensive archaeological work done and we can now say that Petra was once a thriving city with a large population.

One discovery that blew the nopopulation theory was a magnificent mansion unearthed on the hill beside the Roman road. Richly furnished and 1,100 square metres in area, it was built in the first century AD. The walls were colourfully decorated, and there undoubtedly would have been many more such mansions in Petra.

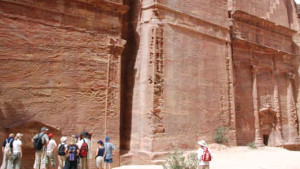

The first sight that greeted visitors was the siq, a 1.5 km ravine providing access to the rose-red city. Ever since Burckhardt found it the siq floor has been composed of dust and stones, but a Swiss team undertook the major task of clearing all the rubble down to the original paving stones, in some places more than 2m deep. They even exposed a relief of a camel and its driver carved into the wall of the siq.

The depth of the excavations can be readily seen by a sharp line between the fresh lighter colour of the siq wall that has been exposed and the darker colour of the rock above that has been exposed to the elements for centuries.

On the south side of the Roman road rose a free-standing temple known as “Qasr al-Bint,” dedicated to the Nabataean god Dushara. Then archaeologists discovered a temple to his consort, the goddess Atargatis, on the other side of the Roman road. Her temple is now known as the “Temple of the Winged Lions” because of the lions carved into the stone.

More recently a large temple was discovered to the east of Qasr al-Bint. Even more surprising was the ornamental pool and garden terrace adjacent to this temple. In the centre of the pool was a pavilion, lavishly ornamented with floral sculptures painted red, blue and white. Petra was a real garden city. This of course required much water, a commodity scarcely available in Petra itself, but the Nabataeans carved a channel on each side of the siq to bring water from the spring at Wadi Musa outside the city. There were also two other springs from which they could channel water

Besides the channels, rock cisterns collected water in the rainy seasons. One huge cistern capable of storing 327 cubic metres of water was unearthed beneath the Great Temple. This could have supplied much of the water for the pool complex. Beside the garden and pool there were other sacred pools, fountains bubbling with running water, artificial waterfalls and baths.

icial waterfalls and baths. In the face of a cliff below the “High Place,” water was channelled down from the summit. The water poured out of the mouth of a lion carved into the rock and into a basin below. Lower down the valley is the so-called “garden tomb,” now recognized as a villa instead of a tomb. Just above this house was a holding tank from which water cascaded down in a waterfall to a pool outside the residence. Another waterfall gushed down from the rock beside the “Palace Tomb.”

There was also a swimming pool for residents to frolic in. It now seems that the aqueducts bringing water into Petra were not primarily to provide drinking water for the inhabitants but to supply water to the public baths and fountains, gardens, flour mills and public toilets. It is more likely that their drinking water came from the cisterns dug into the rock.

A recent edition of Near Eastern Archaeology (NEA) is almost entirely devoted to the latest archaeological developments in Petra and details the discovery of the “Great Temple.” Since 1993 archaeologists from Brown University, USA, and from the Jordanian Department of Antiquities have been working there to excavate and partially reconstruct the temple.

Some fallen stone drums that once formed columns had toppled but were visible on the surface before excavations began, betraying the presence of a building. But the archaeologists were not prepared for the magnitude and complexity of this temple, probably built in the first century AD by Aretas IV, the king who tried to apprehend St Paul in Damascus (1 Corinthians 11:32).

Apparently associated with the temple was a small theatre seating about 640 spectators. Whether this was for religious meetings, theatrical performances or music, can only be guessed at. The larger theatre carved into the hillside further up the valley must have held about 4,000 people. An unusual feature of the temple was the carved elephant heads that adorned the tops of the columns supporting the temple roof. The elephant heads are exquisitely sculpted, even giving the appearance of personality for each head. There were once a staggering 156 capitals with Indian elephant heads. Five complete heads and 429 fragments from other heads were found.

Adding greatly to our knowledge of the history of Petra has been the discovery of no fewer than three churches. One is rather small with an apparently private entrance, possibly reserved for the bishop of Petra, but the others were for public worship and must have held hundreds of worshippers. Besides that, the “Urn Tomb” was converted into a church, while the “Cathedral Church” was carved out of the rock.

The earliest of these was the “Ridge Church” which did not seem to have a either a pulpit or benches along the side for believers in attendance. The “Petra Church” yielded the bestpreserved baptistry ever found in the Middle East and has some fine mosaics on the floor. The Ridge Church and the Petra Church even have wall mosaics. The “Blue Chapel” was so named because it had four bluish granite pillars brought from Egypt. These pillars have been restored to their standing position.

Unfortunately, after Petra passed into oblivion, roving Arabs dug up some of the mosaics hoping to find tombs that might contain valuable grave goods beneath the floor.

In the fourth century AD a major earthquake hit Petra and partially demolished these churches, toppled the columns of the Great Temple, the Qasr el Bint and the Temple of the Winged Lions. The Blue Chapel complex was abandoned, though it seems that the four blue columns did not come down until another earthquake hit in 748 AD.

The damage did not seem to have retarded growth of the Christian population in Petra. But the 7th century saw a drastic decline in the population. The cause of this is still debated. The NEA article suggests that the system of channels bringing water into Petra may have fallen into disuse and without motivation to repair it the population sought water sources elsewhere.

It is highly likely that the Islamic invasion of the 7th century had some influence on this drop in population, though there is no evidence of persecution driving the people out. Maybe it was more a matter of government neglect of the city. The welfare of a predominantly Christian population would hardly have excited the concern of the Islamic state.

Paradoxically, a disastrous fire in the Petra Church at the end of the 6th century turned out to be a bonus for archaeologists. A collection of papyrus documents was stored at the church. Without the fire these documents would undoubtedly have decomposed, but they were carbonised by the fire, thus ensuring they survived the centuries. It was not easy opening them because the scrolls were brittle and could not be unrolled. However they were cut into pieces and the writing was readable.

There were 140 papyrus rolls. One referred to the “Blessed and all-holy Lady, the most glorious mother of God and ever-virgin Mary.” Probably this church was dedicated to her. The other documents are mostly commercial in nature. Marjo Lehtinen called them, “One of the most important discoveries of ancient documentary texts outside Egypt” (page 277). The size of the rolls varies from small half-sheets up to scrolls 8.5 metres long. Written in Greek, the texts deal with property, taxes and dowries.

One of the texts consists of “an accusation of theft written by a priest whose spelling skills leave a lot to be desired. The priest, Epiphanios son of Damianos, apparently rented an apartment to a fellow cleric, Hierios, son of Patrophilos, who, when he moved out, failed to return certain items belonging to Epiphianos. Among these items were a large key, six birds and a table” (page 278).

Another papyrus tells of the longstanding argument between two deacons who had some contention over a shared courtyard, water from a downspout, and a vineyard. The issue was argued in front of two arbitrators. All parties involved swore on oath to live peaceably hereafter and duly signed the document. We hope they buried the proverbial hatchet.

Donations to the church and to the poor and needy were freely given by early professing Christians and two of the texts deal with such donations. One of them must have been of considerable size because a hospital was built with the proceeds.

The most visible evidence of Nabataean occupation of Petra is the 800 or more tombs carved out of the cliff faces all through the city. They are particularly attractive to tourists because the sandstone of Petra was laid down in sharply defined layers of different colours. Originally the ceiling of each tomb would have been of the one colour, but over the centuries portions of the ceilings have collapsed in irregular patterns exposing different coloured layers. The result is a brilliant display of variegated colours.

But recent discoveries have exposed a different type of grave— shaft tombs cut into the ground. Two such tombs have recently been excavated. The grave goods buried with them had not been looted and provided an insight into this type of burial. As was common practice in those days, the bodies had been allowed to decompose and the skeletons subsequently interred in the graves. One of the graves contained the skeletons of 36 individuals who lived during the second half of the first century AD.

Petra was once an illustrious city enjoying wealth and reputation, but it all came to a dramatic end. The prophet Jeremiah wrote, “O you who dwell in the clefts of the rock, who hold the height of the hill! Though you make your nest as high as the eagle, I will bring you down from there, says the Lord. Edom [the original inhabitants of Petra who were the descendants of Esau, also known as Edomites] also shall be an astonishment; everyone who goes by it will be astonished... No one shall abide there” (Jeremiah 49:16-18). The last sign of occupation in Petra was a Crusader castle built at the end of the valley, but when the Crusaders left, the valley lapsed into silence for 600 years until Burckhardt stumbled on it and returned to tell an astonished world of this “rose red city, half as old as time.”