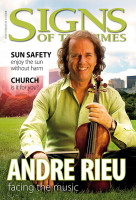

Jokes and laughter. Bright, coloured costumes. Clapping and whistling to the music. Balloons falling from the stadium roof onto the audience. This is far from what you would expect at a classical concert of waltzes and arias but it's exactly what you get with Andre Rieu. You can see the absolute delight on people's faces when he performs.

It is a completely absorbing experience that has captivated millions of people around the world. Such a reaction to his music has surpassed all of Rieu's expectations but has fulfilled the dreams that have been with him for as long as he can remember.

When your father is the conductor of a large orchestra, music is guaranteed to play a major role in your life. From the age of five, a very little Rieu took his very big violin to lessons twice a week and practised for an hour each day.

There were many times when he would stare out the window, half-heartedly repeating scale after scale while neighbourhood children were playing outside but even at such a young age, he was in awe of the beautiful sounds this instrument could produce and had a strong desire to master it.

As Rieu grew older, his parents introduced piano and recorder lessons and, at one stage, he studied the oboe. He and his younger brother, Robert, also sang in the church choir. The two children never wanted to go and would constantly make up excuses to get out of choir practice and, sometimes, when they were out of excuses, they'd simply run away and hide. Strangely, once they were immersed in rehearsal they quite enjoyed it and relished the weekly performances at church.

Looking back on his high school years, two things stand out for Rieu: “Study and practice, practice and study.

I can hardly remember doing anything else. School, violin ... violin, school ... it was all just a treadmill that never stopped.”

Things didn't get much easier when school was over. At the age of 24, Rieu left his home in Maastricht and moved into a small, dilapidated apartment in Brussels to study violin at the Brussels Conservatory of Music. His teacher, Andre Gertler, was famous not only for his outstanding teaching abilities but also for violent mood swings and intolerance for the slightest musical flaw. Because he was so demanding, Rieu and his classmates did little else than practice, which left no time for making friends. While Rieu admits he learned a lot from Gertler, he says, “All in all, my life in that big city where I hardly knew a soul was, to tell the truth, a big disappointment... . For the first time in my life, I was lonely and extremely unhappy.”

Fortunately, things turned around for Rieu when he was reunited with a girl from his childhood and fell in love.

Marjorie had been in Rieu's sister's class in high school and they had met at a party held at the Rieu house when Rieu was 13. Over the years, their paths would cross occasionally but with both so busy with their studies, they didn't pay much attention to each other. It wasn't until they met again 12 years later at a concert by Rieu's sister that “the little pilot light still burning in both of us flared up into a great big flame, never to be extinguished.”

Rieu believes his relationship with Marjorie is the foundation for his success.

He says, “Our love has been a source of inspiration for both of us— then, as well as now. Without our love, which has enabled us to collaborate companionably with not trace of competition, I would never have made it to the top... . All the success I now enjoy I owe to our having fought for it together.”

But it wasn't musical success they first sought. After 26 years of nothing but violin, Rieu put the instrument in its case, locked it, pushed it into the back of a closet and threw the key into the Maas river. He left the Brussles Conservatory without notification and attempted to catch up on all the things he'd missed as an adolescent. Namely, “hanging around doing nothing, and discussing profound matters like God and the universe.”

After realising his new choice of lifestyle was not going to pay the bills and not wanting to leave all the breadwinning to Marjorie, the couple decided to go into the pizza business. Without any capital, their idea was to start with a small market stall and gradually work their way up. “Marjorie, with her college degree, would be the waitress, ... and I—after practising the violin for more than 20 years—would be the cook.” As their speciality, they would serve “Pizza Paganini”—a dish that came with a personal performance of a Paganini piece by the chef. Feeling that he might be a little rusty on the violin, Rieu took it out of the cupboard and rushed back to the Conservatory to brush up on his Paganini. When Gertler heard him play, he was astonished.

He said, “Fantastic! Unbelievable! Andre, it's a miracle! Who's been giving you lessons all this time? You've made such incredible progress!”

Needless to say, the pizza business idea was immediately dropped.

Rieu and Marjorie moved back to Maastricht in 1978, where he met up with a former classmate who was in the process of putting together a six-piece salon orchestra. The music they played was much lighter than the intense classical pieces Rieu was used to and he took to it immediately. He says, “A whole new world opened up for me. I was seized by the beat that was later to become virtually the rhythm of my life: the beat of three-four time, the waltz.”

During this same year, Rieu's first son, Marc, was born. Rieu had a job playing with the Limburg Symphony Orchestra and felt, with fatherhood around the corner, he couldn't afford to waste time on unprofitable hobbies.

So he took over the informal six-piece and set out to turn it into a professional ensemble with regular engagements.

One of the problems he faced was the salon orchestra's very limited repertoire.

Because of his strictly classical upbringing, Rieu didn't know where to begin looking for the kind of lighter pieces to suit the orchestra's style. Marjorie's father had been a music lover and collected more than 500 records during his lifetime. Marjorie brought the collection down from the attic and together, they sorted through them and came up with the perfect repertoire.

More problems arose when a thorough search through numerous music stores and bookshops failed to produce any sheet music for the pieces they had selected.

Determined to find what they were looking for, Rieu and Marjorie approached the local newspaper.

They advertised their ensemble as the Maastricht Symphony Orchestra and requested that people send in any old sheet music they might have lying around. The response was overwhelming.

Boxes and boxes of music arrived and another sorting session began.

“Finally, of the countless boxes of music, one pile was left with about 100 pieces, which we arranged for our orchestra. And, as fate would have it, all of these first pieces of ours eventually became hits,” says Rieu.

Of course, having a repertoire means little if you don't have an audience.

Being that the Maastricht Symphony Orchestra specialised in music of “the good old days,” Rieu decided to try to book concerts at various nursing homes. This was met with much enthusiasm and, at every concert, they would receive an invitation to play another concert at another institution. “Soon nursing homes and rehabilitation centres had to make way for concert halls and theatres,” says Rieu. “But I'll never forget that it was there, in the presence of all those elderly people, that the career of the Maastricht Salon Orchestra was born.”

Watching the reaction of the nursing home residents revealed the power of music to Rieu. “You can make people really happy with music, driving away their sorrow, pain and loneliness for a while and giving them the illusion, at least for a couple of hours, of a better life.”

Rieu also noticed the audience seemed to want more than just music and felt he should try to interact with them. “In the beginning though, I was so shy I could hardly get a word out,”

he says. But the audience loved it and, as more concerts were booked, his confidence grew. with Nick Mattiske These days, Rieu is famous for his on-stage charisma and “talky” style of performance. He believes a sense of humour can engage an audience in a very special way. And sometimes, this can happen in very unexpected ways.

At one concert, Rieu was inviting the audience to whistle when a particular part of a waltz was played. To explain it, he said, “Just watch Frans, then you'll know exactly what to do.” At that very moment, Frans, the second violinist, crashed through a loose plank in the stage floor. Fortunately, no-one was hurt but everyone laughed until there were tears in their eyes.

With the success of the Maastricht Salon Orchestra, and the knowledge he gained from promoting his music and organising concerts, Rieu decided to branch out. In 1987, he founded the Johann Strauss Orchestra and his own company, Rieu Rieu productions.

Marjorie had a natural instinct for business. When she was eight, she catalogued her extensive collection of books and loaned them out to the neighbourhood children for two cents each. At age 10, she gave ballet lessons to her friends in her bedroom for 10 cents an hour. So while Rieu was looking for a manager for his company, Marjorie offered to step in until he found one. Twenty years later, she is still the manager, and loving it.

The forming of the Johann Strauss Orchestra was not without its problems. “There were many times when I was so discouraged I wanted to give up,” says Rieu. “Deep down inside, I was convinced that all this drudgery would eventually lead to something good.” Rieu's hard work, passion for music and desire to bring joy to audiences around the world motivated him through those hard times, and led him to the success he is experiencing today. His gold records, DVDs, TV appearances, top 10 hits and sold-out shows are testimony of what a little boy with a big dream and a violin can achieve.

Having flowers and chocolates named after you is quite an honour but the biggest honour for Rieu is seeing how his music moves people. His greatest wish is to “go on making people happy with music for many years to come!”