King Hezekiah ruled over Judea in Jerusalem 729-686 BC, including a co-regency of 14 years with his father Ahaz. During his reign the Assyrians under Sennacherib invaded Judah and besieged Jerusalem.

This is referred to in 2 Chronicles 32:30: “Hezekiah also stopped the water outlet of Upper Gihon, and brought the water by a tunnel to the west side of the city of David.” An article by T C Mitchell in the 2005 edition of Buried History draws attention to some recent information about this tunnel.

The tunnel is more than 500 metres long and the workmen started at both ends. They did not dig in a straight line to each other but seemed to meander in various directions before meeting in the middle. There has been much speculation as to why they pursued such a circuitous route. There seems to be no logical explanation, but obviously they must have had a good reason because this would have added many metres to the length of the tunnel, and made it more difficult to meet in the middle.

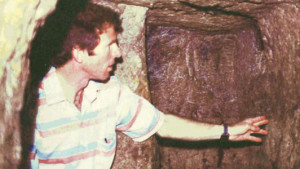

Mitchell notes that “the workmen who excavated the tunnel probably used picks, or axe-like implements, rather than chisels” (Buried History, page 43). That is hardly in doubt as the curved pick marks can be clearly seen on the sides of the tunnel. In fact it can be concluded from the pick marks alone where the workmen met. The pick marks curve away from the direction in which they were digging.

The tunnel is only wide enough for one person and as the stone chips were dislodged they must have been passed back in baskets by a chain gang to the outside. The deeper they got into the tunnel, the more men would have been involved in the chain gang.

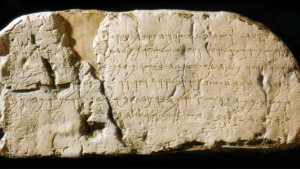

An inscription telling how the men worked, and how they met in the middle, was chiselled into the wall of the tunnel near its outlet at the Pool of Siloam. In part it says, “This is the story of the boring through. While [the tunnellers lifted] the pick-axe each toward his fellow and while 3 cubits [remained yet] to be bored [through, there was heard] the voice of a man calling to his fellow—for there was a split (or overlap) in the rock on the right hand and on [the left hand]. When the tunnel was driven through, the tunnellers hewed the rock, each man toward his fellow, pick-axe against pick-axe. And the water flowed from the spring toward the reservoir for 1200 cubits.”

Mitchell states that the inscription was first noticed in 1880 AD when one of Conrad Schick’s students fell into the water near the tunnel exit. At that time the lower portion of the inscription was below water level and the tunnel had to be deepened to lower the level of the water.

The following year, paper squeezes and a gypsum cast were made of the writing and Archibald Sayce translated it. In 1890 the inscription was chiselled out of the rock wall and as Palestine was then under Ottoman rule, the inscription was sent to Constantinople. It is now in the Istanbul Museum.

As it is seen now, it is cracked and some pieces are missing. It has been assumed that the person who chiselled it out of its place was not very proficient and was responsible for its faulty condition, but Mitchell claims that a tracing made of the inscription in 1881 indicates that “it was already in this damaged condition before it was removed” (page 45).

Based on the style of the writing this inscription has been dated to about 700 BC, which would be the time of Hezekiah, but some critics have rejected this date for the inscription and the digging of the tunnel itself. Some have dated it to 300 BC, and some even to the Roman period. A recent analysis has at least confirmed the date for the digging of the tunnel.

When the tunnel was hacked out, it was sealed with a layer of lime plaster to prevent water being absorbed by the rock walls and floor. Recently a boring was made into some area of this plaster and beneath it was found a small piece of wood and a portion of a plant. These were sent to a laboratory for carbon dating. The wood yielded a date of 2620 years of age, and the plant 2505 years at time of testing. Radio carbon dating cannot be regarded as precise but this test puts the tunnel in the vicinity of the time of Hezekiah.

Another dating method, probably less reliable, was used to date rock. It is called “radioactive thorium and uranium dating of calcite speleothems formed by water seeping through the rock” (page 45). These gave dates of about 300 BC.

In the absence of firm evidence to the contrary there is no good reason to dispute the biblical date of about 700 BC for the digging of the tunnel and the inscription left by the contemporary scribes.