It was the 1960s. Australia was experiencing amazing postwar economic growth, fuelled by an increased labour workforce of new immigrants. By the middle of the decade, Australia boasted the secondhighest standard of living in the world.

In contrast, the poor state of its indigenous people had gained more attention both within Australia and internationally.

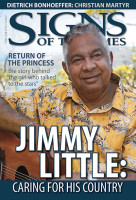

One of the few Aboriginal people to be successful in the wider Australian society at this time was a quietly spoken young man from the bush. His name: Jimmy Little. He was Australia’s first Indigenous pop star and in 1963, had a hit with the song “Royal Telephone,” which became his signature tune. He was a regular performer on “Bandstand” and “The Teen Scene,” and was voted Pop Star of the Year in 1964.

Although Jimmy enjoyed fame, his people were not allowed to vote in Australian federal elections, nor were they included in the national census. Over the course of several years, about one million signatures were collected in petitions, calling for legislative reform.

In 1967, a referendum was put to the Australian people, proposing that Aborigines be not only counted as Australian citizens but also included in federal legislation. An overwhelming majority of almost 91 per cent of voters supported the amendments. The 1967 referendum became a significant milestone in Aboriginal history—a symbol of Aboriginal political and moral rights.

Now 40 years later, “Uncle Jimmy”— today a 70-year-old elder—reflects on the changes he has seen.

“As a boy, I lived on the Aboriginal reserves of Cummeragunja and Wallaga Lake [both in New South Wales].

We lived in a tin shack, cooking was done over a fire, and we went hunting and fishing. We walked or rode horses; there were few bicycles. There was fruit picking, timber mills and a dairy where people could work. Everyone lived a simple life. The elders taught us kids the culture and traditional ways. At the same time, our parents prepared us for the modern world. We were encouraged to learn the new ways.

“I think I had a normal childhood— but looking back, I see that I was one of the few who found life’s opportunities. I still had to earn my way, though I had a lot of support from my family and extended family.” With this positive upbringing, Jimmy Little had confidence to follow in his parents’ footsteps, starting a career in entertainment. By the age of 19, he had performed all across New South Wales and on radio. He cut his first record in 1956 and toured in the United States.

His musical career skyrocketed and he was also cast in a Billy Graham film, “Shadow of the Boomerang.” He met and married Marjory in 1958, who became a strong support for him.

His calm persona won admirers everywhere he went. However, the political scene began to simmer and Aboriginal issues were brought to public awareness. In many parts of Australia, Indigenous people were dispossessed of their lands and their culture. In February 1972, Aboriginal activists Garey Foley and Chicka Dixon erected a “tent embassy” on the lawns of Parliament House in Canberra to protest against the then-government’s stance on Aboriginal land rights.

With his high profile, Jimmy Little was criticised for not being more outspoken on Aboriginal issues. “You can catch flies two ways—with vinegar or honey. I chose the honey,” he explains. “Everyone is gifted to do something in life. Some people are gifted to become politicians, sports people or medical doctors. I looked at myself and thought, What have I got to offer?

“My talent lay in music, so that’s the path I chose to follow. In contrast, my daughter, Francis, later became involved in protests and demonstrations. She wanted to see justice done for past wrong deeds in Aboriginal history— and I am very proud of her.”

Jimmy’s musical success continued steadily throughout the 1970s. In this decade, he also became chairman of the Foundation for Aboriginal Affairs. The 1980s brought new musical sounds that pushed Jimmy’s quiet country style of music out of the spotlight. He decided to refocus his energies, and so began teaching and mentoring Indigenous music students at the Eora Centre in the Sydney suburb of Redfern in 1985.

He spent time speaking at schools, workshops and courses across Australia.

“This country made me who I am; I wanted to give back something to show my appreciation,” he says.

He also went on a three-month tour of Aboriginal communities where he witnessed the terrible effects of Aboriginal dispossession. Poverty, depression and squalid living conditions left young people and the elderly dying from substance abuse and sickness.

“In the past, we had a self-sufficient lifestyle. We had everything we needed.

The land is everything to Aboriginal culture—it provided hunting, fishing, food, a living—it was the recreational centre, the educational institution and held the sacred religious stories.

“Now that society has encroached on the land, Aboriginal lives have changed. There’s no hunting—only shopping for processed food in the supermarket.

In the Northern Territory especially, mining has meant less land is available for the people to practice their culture. People don’t want to leave their home to get educated but without it, they cannot make it in the white man’s world.” Uncle Jimmy admits the problems in today’s Aboriginal society are complex and the solutions are not easy.

Indigenous Australians have a higher incidence of chronic health problems such as kidney disease, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, ear and eye problems, and asthma. Health and social problems result in an overall mortality rate five times greater than non-indigenous people in the 35 to 54 age bracket.

Some problems stem from internal conflicts. Uncle Jimmy—who is a nonsmoker and non-drinker—explains: “The television and media bring us so many immoral influences, and show us a life that is not right for us. We become discontent and feel imprisoned in our own lives. We live two lives—the dream life and reality. When our reality is no good, we escape to our dream life. This is why people abuse alcohol or drugs.” Although the statistics on alcohol consumption among Indigenous people are similar to the general Australian population, it has a greater impact on Indigenous society. Many Aboriginal communities have taken initiatives to declare their locality “alcohol-free” zones, or limit the amount or type of alcoholic drinks allowed into the area.

In a small victory, the rate of chronic disease in the Indigenous population is slowing—probably due to a greater number of community health services now available, since funding was first injected into Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander areas more than 30 years ago. These local clinics, often run by Indigenous people, are able to treat and help prevent health problems.

Uncle Jimmy has experienced firsthand the impact of chronic kidney disease, spending two years on daily dialysis. He visited renal clinics and community centres across Australia, performing for patients and staff. He demonstrated that a productive life is possible, even while on medical treatment and successfully underwent a kidney transplant in 2004.

In mid-2006, he formed the “Jimmy Little Foundation,” to assist Indigenous people in accessing vital health services, particularly those in remote areas.

“I want to be an example, to encourage others to live a healthy life, to pick themselves up and have hope.” Uncle Jimmy’s own faith and hope inspires him to share with others. May 2000 saw a massive demonstration of public support for black and white harmony.

Jimmy Little was one of a quarter of a million people who walked across the Sydney Harbour Bridge in a “Walk for Reconciliation”—he sang and played his guitar all the way. He says, “Reconciliation is a never-ending word.

We have to deal with it daily, person to person, all through our lives.” While there are many matters yet to be resolved in Aboriginal society, Jimmy Little sees hope for the future. He strongly believes in the power of individuals being involved in their neighbourhood. “If we all just kept to ourselves, our own happiness would be no more than the happiness of our household,” he says.

“Yet if we got involved with our neighbours and our community, our happiness would be multiplied through all the others in our circle.” While Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders are a minority in Australia, their issues, like the many various groups in our multicultural society, have relevance for us all. We have an obligation to connect with those around us. As Uncle Jimmy says, “Our extended family is the human race.” Jimmy Little’s quiet inspiration complements the achievements of other Indigenous Australians who have made an impact on their society.

For him, it’s reassuring to see more and more Indigenous people making a difference in their respective arenas. Uncle Jimmy affirms, “I care about life and I’m not the only one.”