Two months of surveying and excavating in a large, open area along ' the south side of Petra's main colonnaded street (the so-called "Lower Market") have generated exciting new information about this area, and its relationship to the adjoining Great Temple and other monuments in the city's civic centre.

The work has been directed by Leigh-Ann Bedal of the University of Pennsylvania, in collaboration with the Brown University excavations of the Great Temple, directed by Martha Sharp Joukowsky. In 1998 they identified a series of associated structures and facilities that include an ornamental pool with island pavilion and an elaborate system of water conduits converging onto an adjacent terrace.

Ms. Bedal now believes that rather than a marketplace, the Lower Market area "was apparently a place of refuge an ornamental garden within the city's civic centre, knownas a paradeisos in Greco-Roman times." She explains that "this unique discovery is the only example of a formal garden known from Nabataean contects, and the only archaelogically known exmple of a public garden in the region."

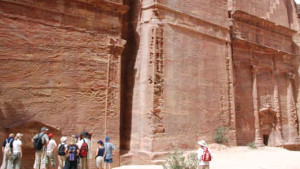

The large open area in question is locared in the centre of the ancient city, overlooking the colonmade shop-lined street from the south, and surrounded by temples and other public structures that defined the city-centre. The area,created by cutting deep into the side of a rocky slope,is perched on a large earthen platform. Its monumental scale and stragtegic location in the city-cenre prompted scholars earlier this century to assume that it must have plaued an important role in the organization and life of Petrea, Ms Bedal said.

The Lower Market on Two Terraces

The Lower Market area measures 75 X 82 metres, covering a total of 6,150 square metres. It is made up of two terraces. The northern (lower) terrace rises more than six metres above the Colonnaded Street. The excavations concentrated on the south half of the Lower Market where the ground surface showed numerous architectural features on the southern terrace, an artificial platform that was partially created by quarrying into the rocky slope to the south and east, leaving a 16-metre-high vertical rock escarpment. The prominent east-west wall that bisects the site was found to comprise three walls of different construction and from different time periods: Nabataean-Roman, Byzantine, and post-Classical (Medieval). The post-Classical wall was of poor quality construction that served to direct the water down to an agricultural field on the northern terrace. A cooking pot found in the wall "indicates that the Lower Marketss may have been cultivated by the Crusader andfor Bedouin inhabitants of the 12th century, an activity which persisted into the modem era with the continued use of the wall and field terrace by the Bdoul Bedouins who have lived in Petra for several centuries," Ms. Bedal said.

Pool with an Island

The earlier monumental east-west wall, 2.5 metres high and 3.5 metres wide, was traced up to 50 metres across the width of the Lower Market. It was well built, in a typical Nabataean style of alternating rows of sandstone blocks and rubble bonded with an impervious white mortar.

The excavation showed that this wall acted as a retaining wall for a monumental pool, measuring 46 X 23 metres and 2.5 metres deep. The pool walls and floor were lined with a thick layer of gravel-tempered hydraulic cement. A stone staircase built into the northeast corner provided access to the water. Four rectangular paving stones on the edge of the pool were identified as the remnants of a promenade that once encircled the pool's perimetre, Ms. Bedal said.

At the centre of the pool is an island-pavilion measuring 11.5 X 14 metres with a bridge that provided access to the island from the promenade. The pavilion was open on at least three sides, with a wide front entrance measuring 4.5 metres across. The interior walls were plastered and decorated. The excavation revealed fragments of moulded and painted stucco (pompeiian red, orange, and bright blue colours), marble volutes, a five-petalled flower, and numerous fragments of worked marble and other imported coloured stone.

The island pavilion in the centre of the pool, the decorative elements, and other factors indicate to Ms. Bedal that "the pool had a recreational function as opposed to the purely practical function of a reservoir." The pool's retaining wall also served as an aqueduct that carried water from cisterns on the southern slopes overlooking the site. Water was directed to the centre point of the wall and into a castellum divisorium. This was a central holding tank with a capacity of nine cubic metres that collected water and then redistributed it in various directions, through conduits, stone channels, and ceramic pipes that were used for irrigating the garden on the northern terrace.

The Garden was a Paradise

Ms. Bedal explains that ornamental gardens, orparadeisoi, were introduced to the Mediterranean world following the eastern campaigns of Alexander the Great in the 4th century BC.

"The paradeisos was an important element in Hellenistic palace complexes, part of the recreational facilities which included pavilions, pools, fountains, promenades, aviaries, zoos, and theatres. In the Roman world, the Hellenistic tradition was further developed with gardens becoming an important element in both the private and public spheres," she said.

Paradeisoi from the Hellenistic and Roman periods have been identified in Palestine and Jordan. One example is Hyrcanus the Tobiad's palace at 'Qrus modem Iraq al-Amir, west of Amman, built in the 2nd century BC. The Hasmonean dynasty of Judea in that same period built a winter palace at Jericho, set in a large paradeisos intermingled with pavillions, banquet alls, enclosed garden and swimming-pools. Herod the Great in Judea (34-7 BC) also had several private palaces at Jerusalem, Caesarea, Masada, Jericho, and Herodium with ornamental gardens and parks as well as monumental swimming pools.

Ms. Bedal believes the pool- pavilion at Petra was first built in the early 1st century AD, adjoining the great temple as part of a large palace complex for the Nabataean King Aretas IV ( 9 BC-40 AD). Excavations in the great temple show that this structure was converted into a public assembly hall by the early 2nd century AD, at which time the garden became a public space. The pool continued in use into the 4th century. The pavilion walls collapsed and filled the pool with debris, probably during the great earthquake of 363 AD.

Was the Temple really a Palace?

Some scholars working at Petra have suggested that the great temple was not a temple, but rather formed part of a palace complex. This scenario is partly bolstered by the discovery of the garden, pool, and pavilion. The excavations at the adjacent great temple have not yet provided proof of the date and use of the original structure, so it could turn out to be a temple after all.

The urban setting of Petra's paradeisos, Ms. Bedal says, corresponds to the Roman concept of public gardens. "A garden would have offered a refreshing retreat from the inevitable hustle and bustle of the city's Visitors could lounge by the visitors to the city after a long journey pool or escape the burning heat of the desert sun by relaxing in the pavilion surrounded by cool water, or stroll through the garden under the shade trees that, presumably, would have been present" she explains.

Petra's garden notes may have served as an oasis that greeted visitors to the city after a long jouney through the harsh desert environment.

The ancient Greek geographer, Stabo, described Petra as "having springs in abundance both for domestic purposes and for watering gardens." Ms Bedal notes