I have an almost pathological envy of people who can speak a second language. As a journalist, I have heard and recorded a wide range of migrant stories, but a strange part of me still resents that my perfectly happy parents didn’t uproot our family and move us to a country where I would have learnt a second language with childlike ease.

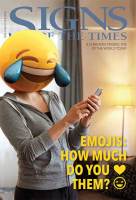

But after three decades of concentrating on the written word, I find myself learning a new multilingual way of communicating that has risen out of Generation Y’s connected-from-birth computer literacy. And though the debates rage red-hot in academic circles as to its benefits (or lack thereof), I find myself thinking that this almost comic way of connecting actually provides us some real spiritual gain.

If you and I were communicating via text on a mobile phone, chances are you wouldn’t have any problems understanding me if I signed off, “lol.” In fact, if I wrote “LOL” you’d know I really meant it. That’s because this abbreviation for “laugh out loud” has become synonymous with a new style of conversation dominating digital realms. Technically speaking, it’s called an initialism.

Lol has become one of the three most recognised examples of internet slang since this way of speaking first emerged on Usenet, the worldwide ancestor of computer forums that was launched in 1980. The other two are BFN (Bye For Now) and IMHO (In My Humble Opinion). Many more initialisms aim at conveying physical responses that are a step away from just plain words, take ROFL (Roll On the Floor Laughing) for example. Now, there’s nothing terribly new about acronyms in written communication. But if you’re struggling to understand them, then rest easy—they’re almost obsolete.

The quest to increase the humanity of computer communication soon resulted in the rise of the emoticon. And so twentieth century users of Japan’s ASCII NET collected together punctuation marks to create symbols that served the same purpose as body language. Behold! Professional communicators the world over shuddered as the wink, ;o), arrived online. These pictorial representations of facial expressions aimed to add mood to the speaker’s words.

University lecturers were the first to make dire predictions. Writing in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution back in 2003, Silvio Laccetti and Scott Molski from the Stevens Institute of Technology, made the statement, “Unfortunately for students, their bosses will not be ‘lol’ when they read a report that lacks proper punctuation and grammar, has numerous misspellings, various made-up words and silly acronyms.”

Strangely though, the sky did not fall and, for all of the criticisms, the trend didn’t die out but gained an imprimatur even more sacred than that of ivy-draped institutions: commercial acceptance.

Emoji—miniature graphics that simultaneously embraced all of the initialism’s brevity and the emoticon’s expression—were the tipping point. Real smiley faces replaced colons and brackets and were quickly joined by a bewildering array of expressive pictures, practices and household items.

Their initial creator was a Japanese coder named Shigetaka Kurita, who in an interview with digital publication Ignition, says he was continuing a trend of connecting the head and the heart: “When you communicate on the internet, it is very convenient to have emoji, because it’s hard to express emotions only with text. If you look at history, after handwritten letters, there came the telephone. Then, electronic messaging emerged. There was always a demand for something that can express emotions.”

Smartphone users voted with their thumbs. In 2010, hundreds of emoji characters were incorporated into the Unicode Standard. In 2011, Apple released them as part of OS X Lion; in 2013, Google added native emoji support to Android. When the Oxford Dictionary announced that , technically a pictograph and not a word, would be its 2015 Word Of The Year, the war was over.

, technically a pictograph and not a word, would be its 2015 Word Of The Year, the war was over.

And I believe communication was the winner.

![]()

This development in computer-mediated communication isn’t just a collective effort to abbreviate messages. It heralds a desire to connect the head with the heart. Researchers have taken a second look and discovered that there are some surprising benefits to using emoji:

-

We react to them just like we would to a real human face.

A team of psychologists and sociologists in South Australia has proven that “when we look at a smiley face online, the same very specific parts of the brain are activated as when we look at a real human face.”

-

They soften the blow of a critique.

Studies on workplace communication show that when negative feedback comes with positive emoticons, the employees are more likely to feel good about the message and undertake the change requested.

-

They help people understand you.

The International Communication Association has discovered that people who use emoticons in their online communications are perceived as being not only friendlier but more competent, and their messages were much more likely to be understood.

-

They promote happier relationships.

The HR Florida Review published a study that demonstrated that “symbolic emotional cues help ‘clue in’ the recipient towards a particular emotion [and] thereby clarify the intentions of the sender,” resulting in a happier relationship between the two parties.

In short, those pesky emoji can add meaning, improve communication and deepen bonds.

Got room for one more phrase? Memorise the “thousand touch relationship.” This is a term used to describe the way in which the generation that grew up with the emotional shorthand tends to relate to each other. Through social media and short messaging services where these icons thrive, they reach out to each other with a thousand little “touches” a day, sharing experiences and affirming connections. This isn’t the sum total of their relationship; that would be truly hollow. However they incrementally build up their experience and understanding of each other. And Christians should take note: it isn’t just our words that create our witness, but also what we choose to surround them with.

Our race towards more rapid and prolific styles of communication, IMHO, was threatening something profoundly human. Email was all about business; SMS aimed at communicating in as few characters as possible. There was an inherent danger in stripped-back communication that we would actually edit out the care we should be expressing toward others. Our goal to truly connect with each other—a God-given human trait—was being subtly undermined.

The apostle Paul already knew about the mistake we were making in the first century AD. He warned the church at Corinth that the communication of facts—even that of the gospel—without a heart for those who hear amounted to empty words: “If I speak in the tongues of men or of angels, but do not have love, I am only a resounding gong or a clanging cymbal. If I have the gift of prophecy and can fathom all mysteries and all knowledge, and if I have a faith that can move mountains, but do not have love, I am nothing” (1 Corinthians 13:1, 2).

Paul says that when communicating, truth and love must go hand in hand—it’s when we combine our desire to share the message of the Bible with love for those who are listening that we are actually growing up in Christ and being effective.

Of course all this doesn’t amount to anything like the assertion, “If Jesus were alive today, He’d use emoji and publish on Facebook!” Emotion has never been lacking in the written word, especially God’s Word.

You don’t need an initialism to convey Jesus’ heart for the struggling in Matthew 11:28: “Come to me, all you who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest.”

IWGYR wouldn’t make it clearer and Jesus’ call can still be heard by the most technologically challenged. After all, initialisms, emoticons and emoji are tools, not the message. Yet many a person has received additional comfort from seeing verses like these sent and signed “YBIC” (Your Brother In Christ), with the symbol  at the end.

at the end.

Some of those “thousand touches” have reminded them that someone cares, that they’re not going through a valley of shadows alone. And of course that should make sense to us. The Bible and our emotional witness complement each other. Proclaiming the truth of God’s Word and the love of His children for each other should never be mutually exclusive things.