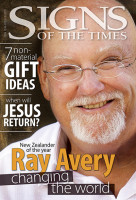

He’s a scientist, an inventor, a husband, a father, a public speaker and he’s New Zealander of the Year 2010. But, more than anything, Ray Avery is a man who loves people.

Avery’s life didn’t get off to a rosy start. He was raised in a series of orphanages in London and by 14 years of age, was living on London’s streets, scavenging for food and spending long hours in the city’s library, where he could at least be warm and dry.

It was from this inauspicious start that Avery discovered an interest in how things work. “I remember, when I was seven, looking at the standard lamp between two of the orphanage beds and wondering where the light in a bulb came from,” he says. “I unscrewed the bulb and the light disappeared. I shook the bulb a bit—obviously the light wasn’t in the bulb. So I put my finger in the socket. There was a huge flash of light, and I discovered electricity!”

Today, he is the CEO and founder of Medicine Mondiale, an organisation that strives to help the poor globally to build a more equitable world.

inventions

Avery has had resounding success with several inventions over recent years. He came to the attention of opthalmologist Fred Hollows, who championed high quality and affordable eye care and good health, at a time when Hollows was looking for someone to set up plants to make intraocular lenses in developing countries.

Within two months of the introduction, Avery was at work in Eritrea in East Africa, designing and commissioning two state-of-the-art Intraocular Lens (IOL) Laboratories, one in Eritrea and one in Nepal.

Long after Hollows’ death, Avery kept working on and refining the product. Today, cataract surgery is not only for the wealthy, but also for the poor, even in undeveloped countries.

Once that job was complete, Avery turned his mind to the next project. He had seen the devastating effects of inaccurate medicine dosage, especially when administered by an intravenous line with nothing more than a roller mechanism to control the flow rate. Not only were fluids administered this way, so were antibiotics, painkillers and anaesthesia. As he pondered a solution to this problem, his mind skipped back to the irrigation system at the orphanage.

To Avery, the irrigation system was more than turning on a tap and letting water flow. It was a series of hoses, which became more and more narrow until the end result was a mere drip every few minutes. Years later, he would apply those same principles in creating the Acuset IV Flow Controller that would control the rate of intravenous fluid dripping into a sick person’s veins.

“In the developing world, in many crisis situations, patients are left to treat themselves, often with fatal results. Now, with the Acuset, medicines and fluids can be safely administered, and it only costs $5 and is totaly reusable,” Avery says.

The intrepid inventor was not going to rest after developing solutions to two significant problems. Avery’s next goal was to develop an affordable treatment for children with diarrhoea.

“Acute diarrhoea is the major cause of death of infants under two years of age, while protein energy malnutrition accounts for over half of all child deaths in developing countries,” Avery says.

“The recognised treatment for life-threatening diarrhoea and protein energy malnutrition is to administer a cocktail of essential amino acids either into the child’s vein or through a tube directly into the stomach. For developing countries, [that sort of ] treatment is too expensive.”

Proteinforte, an instant dried soup containing all the essential amino acids required for health and nutrition, is the result of his labour. As with his other products, Proteinforte is First World technology designed to solve a Third World problem.

latest invention

There’s another project being developed in Avery’s garage. It’s an incubator, specifically designed to be used in unsterile, torrid environments.

“A shockingly high number of babies placed in incubators [in developing countries] continue to die. I asked myself ‘Why?’ Of significance was that 90 per cent of the deaths were associated with upper respiratory infections.”

On closer examination, Avery discovered the problem: sick babies were being placed in an incubator in a non-airconditioned, non-sterile environment—the incubator was never designed to cope with those conditions—and within a short time the bacterial levels were half a million times higher than you’d expect in an incubator in New Zealand.

“Incubators designed for use in sterile environments don’t do anything for sick or premature babies in non-sterile environments, especially when combined with washing the baby in dirty water and dressing them in contaminated clothing,” Avery explains.

For three years, Avery has done the research to provide an incubator that will work in challenging conditions. Using technology based on NASA’s long-haul space flights, a patentable infant incubator has been developed that will be commercially produced next year. What’s more, the shell of the incubator costs a mere $27 to manufacture. Not only will it be manufactured in accordance with recognised international standards, it will be functional and affordable.

Avery’s incubator, the Medicine Mondiale Liferaft Incubator, is not a big square box. It is shaped like a rounded bassinet with a curved lid. It looks like a Moses basket, as though you could pick up the baby in its incubator and cradle it in your arms. Although it is expected to do a life-saving job, the incubator looks compassionate.

limits by knowledge

It is commonly said that a person is only limited by their imagination, but Avery takes this adage a step further, adding, “The only thing that limits your imagination is your knowledge. When I left the orphanage, I had two goals. The first was to have my own light switch; the second was to have my own cycle shop. That was the limit of my imagination.

“Now,” he says, “I have the notion that I can change the world. I know I can change the lives for the better of millions on the planet. The only thing that makes that difference is knowledge. If you have knowledge, that gives you the power to dream much larger than you can if you don’t have that knowledge.”

He adds, “The more knowledge you have, the less failures you have.”

While Avery endorses knowledge, it is glaringly obvious that his special brand of knowledge is heavily underscored by compassion. He doesn’t deny it; but compassion for others is something that perhaps Avery expects ought to be present without having to ask for it out loud. Or perhaps he knows that compassion arises from the heart, that he can educate people but he can’t make people more compassionate.

Where does the money come from to develop these projects? This is where Avery’s incredible talent shines through. He does a lot of the research work himself but volunteers all over the world provide the multiple strands of expertise. Experts in a whole range of disciplines donate their time and energy to make this huge wheel of humanitarianism turn.

Fundraising is a mere 0.1 per cent of Medicine Mondiale’s commitment. There are no people knocking on doors, no overheads for fundraising staff. One hundred per cent of donations is used in the development of the products, but Avery’s emphasis is to encourage people to provide physical, practical help.

“Money is not as valuable as time given,” Avery says. “The benefit of sharing skills and working together counts far more. We make the world more egalitarian by using a percentage of our time to make it a better place.”

point of grace

There’s a story Avery likes to tell about a woman who visits her priest.

“I’d like to make a wish,” she says.

“I will grant you one wish only,” the priest replies. The woman looks at him and thinks for a while. Long moments pass and finally she nods.

“Only one wish,” repeats the priest. “Once you’ve made it, you can’t change your mind.”

“I wish,” says the woman, “that every body would love my son.”

So the wish was granted and the world paid homage to her son. Everywhere he went, crowds followed. Gifts were given endlessly. He was invited everywhere, praise rained down on him. Everybody loved her son, and it was awful.

In desperation, the mother returned to the priest. “I have made a terrible mistake.”

“You have used your wish,” the priest said. “I can do nothing for you.”

The woman begged until the priest relented. “One last wish,” he said. “Then no more.”

The woman thought for a while. “I wish,” she said, “that my son would love everybody.”

And so it was. No longer was the son loved by all. But it didn’t matter. Whatever people said or did made no difference to him. He loved everybody, no matter what.

“I like to think that is me,” Avery says. “I have come to a point of grace in myself and I found that by helping people.”