Bob Dent was the first to die under physician-assisted euthanasia laws in Australia. This was back in September 1996, a couple of months after the Northern Territory had passed its Rights of the Terminally Ill Act.

He pled that this “most compassionate legislation in the world be respected” and was “immensely grateful” that he could end his life in a dignified and compassionate manner.

Bob Dent lived in Darwin and was 66 when he died. He had suffered from prostate cancer for five years. He’d had both testicles removed and described an incontinent, pain-wracked, totally dependent existence. He wore a catheter and a leg bag and required 24-hour care.

“I can’t even get a hug in case my ribs crack,” he said. And he worried about how much pressure and suffering his condition brought his wife.

He left a message aimed at Christians: “The Church and State must remain separate. What right has anyone because of their own religious faith (to which I don’t subscribe) to demand that I behave according to their rules until some omniscient doctor decides that I must have had enough and increases my morphine until I die?

“If you disagree with voluntary euthanasia, then don’t use it, but don’t deny me the right to use it when I want to.”1

Pressure for a gentle death

The word, euthanasia means “good death” or “gentle death”. And anyone who has watched a loved one in pain or struggling mentally and emotionally without relief during the last stages of life will have sympathy with the concept of a gentle death.

For the rest of us, we hear enough stories that make us pause and consider if there isn’t a better way. Then there’s the common analogy: We won’t let animals suffer in that way, why should humans have to suffer?

Lawmakers have been pressured by euthanasia supporters over the past few decades in Australia and New Zealand. Now the sustained campaigning is seeing success.

Euthanasia was first legalised in Australia in the Northern Territory in August 1995. It was in force until March 1997 when the Federal parliament removed the power of its territories to legalise euthanasia.

Unlike the territories, Australian states do have the power to act independently on euthanasia, but bills have failed in Tasmania (2013), South Australia (2016) and New South Wales (2017). In 2017, Victoria was the first state to legalise euthanasia.

The new law allows for voluntary euthanasia or doctor-assisted dying beginning in mid-2019. Under the law, to put it simply, terminally ill individuals over the age of 18 in severe pain and with only six months to live will be able to access lethal drugs.

Meanwhile, in New Zealand, there have been two unsuccessful attempts at introducing voluntary euthanasia. Both “Death with Dignity” bills were voted down in 1995 and again in 2003. A more recent bill passed its first reading in December 2017 (76 votes in favour, 44 opposed). That support indicates that it will likely become law after due process.

“Passive euthanasia” accepted

A century ago, common medical practice was to do everything possible to keep a person alive. That thinking was challenged in 1915 when Anna Bollinger gave birth to her fourth child, a boy, at Chicago’s German-American Hospital. The baby was born blue and badly deformed.

The hospital’s chief of staff, Harry J Haiselden, diagnosed that, without surgery, the child would die. However, “in a decision whose shockwaves would ripple from coast to coast, and mark a milestone in the history of euthanasia in America,” says Ian Dowbiggin in A Merciful End, “Haiselden advised against surgery.”

Instead, he announced that he would “stand by passively” and “let nature complete its bungled job”.

“The publicity surrounding his professional conduct, briefly eclipsing news from World War I, inspired other Americans to speak out in favour of letting deformed infants die for the good of society.”2

His action helped bring a change in attitude. Now, withdrawing of medication or life-saving procedures that would extend life is an acceptable and common practice under these kinds of circumstances. This process has been called passive euthanasia—passive because it allows the natural process of dying to take place without intervention.

What it has done is open up a new field—palliative care.

Palliative care

Palliative care for the dying occurs when healthcare professionals, with the family and patient (if possible), recognise that it makes no sense to continue with aggressive treatment to fight the disease or problem.

“Good palliative care fundamentally remembers that we care for the whole person,” says associate professor Natasha Michael, director of palliative medicine at Cabrini Health, a Catholic hospital in eastern Melbourne. “We don’t just look at the physical needs of the person, we look at the psychosocial, spiritual, emotional, existential needs.

“It’s about quality of life, not end of life,” she adds. A vocal opponent of euthanasia legislation, her call is for better palliative care.3

High profile neurosurgeon Brian Owler, who chairs Victoria’s advisory panel for the assisted dying legislation, recognises palliative care as the “main game” when treating patients at the end of their life and accepts that it will continue to be such.

A divisive topic?

In one sense, euthanasia is not a divisive issue. A May 2016 Vote Compass poll of more than 204,000 Australians had 75 per cent agree with the statement: “Terminally ill patients should be able to legally end their lives with medical assistance.”

However, Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull has warned that end-of-life issues were “fraught with practical difficulties and of course with very significant moral difficulties”.4 And there has been opposition.

While Dent, from his deathbed, identified churches as euthanasia opponents (not all are), religious groups are not the only detractors. The World Medical Association (WMA), for example, wrote to Victorian MPs last year urging them not to vote their bill through.

The WMA argued that it was unethical for a doctor to assist in the death of a patient, even if the patient requested it. “It will create a situation of direct conflict with physicians’ ethical obligations to patients and will harm the ethical tone of the profession.”

In response, the Victorian branch of the Australian Medical Association (AMA) reacted strongly, objecting to both the language of the letter and the claim that doctors would be acting unethically, particularly with the diverse views on euthanasia within the medical profession.5

It should be noted, however, that the AMA’s official stance is that “. . . doctors should not be involved in interventions that have as their primary intention the ending of a person’s life”.6

Theory and practice

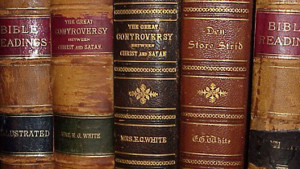

Human life is precious. That’s a given. And, for the Christian, it’s doubly precious because of the sacrifice God made through Jesus for every human—made in God’s image—on the planet (John 3:16).

That makes it easy to say that we should not do anything to hasten death. And many churches and denominations are opposed and have statements against active euthanasia under any circumstances, including my own.7

Fortunately for the vast majority of us, we will never have to face the issue personally. Even if we or a loved one faces a lingering death, the likelihood is that palliative care will keep us comfortable to allow for that sad necessity, a “good death”.

Christians opposed to euthanasia, though, must show grace and understanding when individuals decide to take this last-resort step of assisted suicide. And to have sympathy for those involved, which includes medical personnel.

Mark Carr, a former director of the Centre of Christian Bioethics at Loma Linda University, California, says, “[Christian] physicians want to model the compassion of Jesus Christ. They want to do the best they can to extend Christ’s healing ministry.” However, it can become difficult for them if a dying patient who is in constant pain requests legally available euthanasia, saying something like, “I’ve wrestled with my sense of God’s leading here and the family is agreed with me—they do feel as though God is open to it.”

Carr says it would be difficult for the physician to say, “You know what? I’ve worked with you for 25, 30 years. I just can’t go with you through these last steps. . . . That’s a struggle for the physician, and I hope you can sense that it’s going to continue to be a struggle.”8

Then there’s the person requesting euthanasia. Dent maintained that if he were an animal and in the kind of pain he was suffering, someone would be prosecuted for allowing it to continue. You can understand his thinking.

Now that legal euthanasia appears to be inevitable in parts of our region, Christians, regardless of their personal view, will need to demonstrate compassion for the individuals and to the families of those who make this choice.

There are times when it’s “Christian” to put aside any arguments we may have—for or against certain acts—and to simply be there for people. This is one of them.

2. Michael Manning, MD. Euthanasia and Physician-Assisted Suicide: Killing or Caring?, 1998. https://euthanasia.procon.org/view.timeline.php?timelineID=000022

4. http://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-05-25/vote-compass-euthanasia/7441176

6. AMA Position Statement: Euthanasia and Physician Assisted Suicide, 2016. https://ama.com.au/system/tdf/documents/AMA%20Position%20Statement%20on%20Euthanasia%20and%20Physician%20Assisted%20Suicide%202016.pdf?file=1&type=node&id=45402