Along with awakening interest in their own, nationhood, many erst- while colonies are now demanding the return of their native art and archaeological treasures that are presently displayed in museums and galleries around the world. The long-standing battle for the Elgin Marbles is an example of this.

For many years treasure belonged to the person who found it. In most such cases such treasure was something either not recognised or else neglected by the people to whom it belonged; but valued, restored and cared for by the finder. All that has changed. Practically every country in the world now has stringent laws that prohibit treasure- seekers or even bona fide scholars from removing any artefact from its coutry of origin. Heavy fines or long terms of imprisonment are melted out to offenders.

There is much to be said for and against this new development. However, for anyone who has visited the Cairo Museum and in the gloom strained to read the tatty, yellowed with age and mostly hand- written captions which describe priceless treasures stored in smudged and rickety glass cases: and then seen some of those same treasures during their Australian tour, magnificently displayed in crystal-clear, splendidly illuminated glass showcases with laser printed caption - the contrast is obvious

On the other hand it is only natural that all countries should evince interest in their national "roots" and want to have them at home. Aboriginal skulls have recently returned to Australia after spending decades abroad. Iraq has received back no less than 584 cuneiform tablets which were in American institutes and museumsA 5th century AD mosaic has gone back to Syria, France has returned artifacts to Laos and Iceland has obtained from Denmark two valuable historical documents.

The list could go on, but the latest case under consideration is the famous Siloam inscription which was vandalised and stolen from Hezekiah's tunnel in Jerusalem.

The story behind this inscription is told in the Old Testament (2 Chronicles 32) and backed up by Assyrian secular history. In the 8th century BC King Sennacherib of Assyria ruled the greater portion of the earth. He had already destroyed the ten northern tribes of Israel and now he was bent on conquering the remaining tribes of Judah and Benjamin.

Sennacherib's Siege of Jerusalem

Hezekiah, king of Jerusalem, realised that an attack was inevitable. Sennacherib had already taken 46 cities of Judah and was ready to advance on the capital.

However, Jerusalem was a well- fortified city. Its inhabitants were fanatical nationionalists who were ready to fight to the death for their city and their God. Sennacherib was well aware of this and rather than risk losing many of his men in bloody battles, he decided to use an old and often successful method of subjugation - he would lay siege to the city and starve it into submission.

Accordingly Sennacherib sent messengers ahead in an effort to intimidate the people of Jerusalem. "Doth not Hezekiah persuade you to give over yourselves to die by famine and by thirst, saying, The Lord our God shall deliver us out of the hand of the King of Assyria? Know ye not what I and my fathers have done unto all the people of other lands? were the gods of the nations of those lands anyway able to deliver their lands out of mine hand?" (2 Chronicles 32: 1 1,13)

We have no way of knowing how far ahead this warning was given, but submission by siege was not an unknown tactic and in all probability Hezekiah had already laid in vast stores of food, but storing water was a different matter.

Jerusalem, like nearly all ancient cities, was built upon a mount. Near the base of the mount a never-failing spring supplied the city's water. This spring, Gihon by name, was outside the city walls and close to the floor of the Kidron Valley. A pile of rocks could easily conceal the spring from enemy eyes but that would not allow the inhabitants of Jerusalem to obtain water.

Therefore Hezekiah hit upon the idea of hewing a tunnel through the base of the rocky mount and diverting the spring waters to a pool on the other side of the mountain.

In these days of modern surveying and earthmoving equipment such a project would be quite an undertaking, and for those days it is something in the nature of miraculous. Even now, experts can't work out how Hezekiah's men, beginning at either end and chipping steadily away at the solid rock, managed to come within a few inches of meeting exactly in the middle.

Hezekiah's tunnel measures 1750 feet, almost one third of a mile through solid rock. It is roughly 2ft wide and in places 5ft high and, because of the nature of the rock, does not run in a straight line.

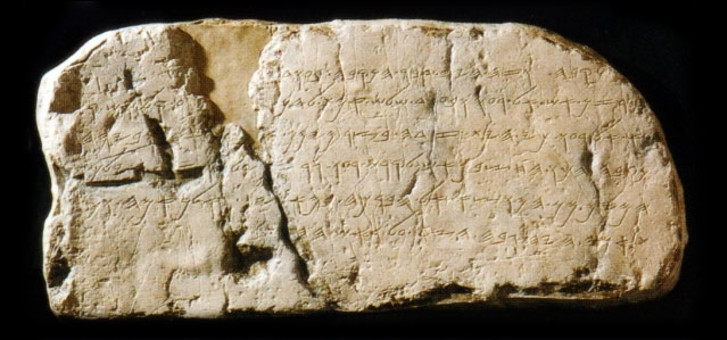

Little wonder that when Gihon's water triumphantly flowed through to Siloam's pool, King Hezekiah immortalized the event with a lengthy inscription. Above water level on the wall close to the Siloam end of the tunnel, Hebrew characters chiselled into the rock read thus: "This is the story of the boring through. While (the tunnelers lifted) the pick-axe each toward his fellow and while 3 cubits (remained yet) to be bored (through, there was heard) the voice of a man calling to his fellow - for there was a split (or overlap) in the rock on the right hand and on (the left hand). When the tunnel was driven through, the tunnelers hewed the rock, each man toward his fellow, pick- axe against pick-axe. And the water flowed from the spring toward the reservoir for 1200 cubits. The height of the rock above the head of the tunnelers was a hundred cubits."

During the thousands of years since 701 BC the tunnel largely fell into disuse and the inscription was forgotten. In 1838 an American explorer, following the directions given in the Bible, rediscovered the silted up tunnel. Forty years passed before some daring small boys swimming in the Siloam pool ventured partway into the dark tunnel and saw the inscription.

News of the discovery spread quickly and before authorities took any action vandals chiselled the piece of rock out of the wall. In their haste, probably spurred on by the hope of instant riches, they broke the inscription into three pieces. Later on these pieces were sold to an antiquities dealer.

At this time Palestine was part of the Ottoman empire and the Turkish authorities confiscated the pieces and sent them off to Istanbul where they eventually found rest in a museum.

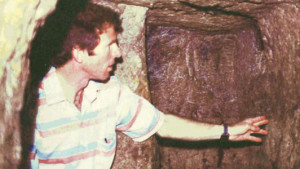

More than thirty years ago Diggings editor visited Turkey for the express purpose of viewing the Siloam inscription. It took a great deal of detective work to trace the whereabouts of the precious stone pieces and when finally located they reposed in a shabby display case in a part of the museum which is seldom visited by the public.

This fact alone is positive proof that the Siloam inscription is of no historical or national significance to the Turkish people. It certainly has no artistic'or aesthetic value either.

Israel is the nation to which this inscription rightly belongs. It is a part of Jewish history and heritage. The elegant paleo-Hebrew letters used in the inscription can be accurately dated to 701 BC which is before the Babylonian exile.

In 1983 the United Nations General Assembly passed a resolution calling for "increased efforts to achieve the return of cultural property to the country of origin. One hundred and twenty three countries, among them Turkey, voted in favour of the resolution. At this present time Turkey is agitating for the return of some of its treasures which are in foreign possession."

According to recent legal text:

- Historic records of a nation; and

- Objects torn from immovable property, no matter where they might presently be, still remain the property of their country of origin.

Without doubt the Siloam insciprtion fits under both of these texts. Besides which, the Siloam inscription is of no significance whatever to the Turks. They do not value it enough to even have it on display in their museum. The inscription is not an artifact to be prized by any nation except the Jews, and even to them the badly broken slab is only of value for what it says - and what it says is mainly of interest to Jewish historians. The Siloam inscription bears not even the slightest relationship to Palestine during the Ottoman occupation.

However, despite the law being on their side, the Israeli authorities have no wish to try to force Turkey to give up the Siloam inscription. Rather they are fervently hoping that Turkey itself will make the move as a gesture of goodwill.