(Please note, what follows contains some confronting ancient texts and inscriptions from the world of the ancient Assyrians.)

The ancient Assyrian homeland in Mesopotamia extended northwest from the mouth of the Little Zab river, a tributary of the Tigris, for only about 130 kilometres (80 miles) along the Tigris itself. The country was not large, hemmed in between the desert beyond the river to the west and mountains on its east, rising just beyond a narrow strip of arable land between them and the river that was much less fertile than in southern Mesopotamia. Naturally, then, Assyria’s most notable cities— Asshur; Kar-Tukulti- Ninurta; Calah; Nineveh and Dur-Sharrukin—were all located along the Tigris.

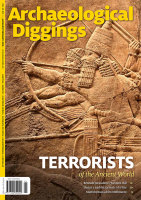

The scarcity of farming land possibly helped give rise to the national character of the Assyrians, who were daring adventurers, brave warriors, talented organizers and an enterprising commercial people. While not a scientific or literary people when compared to their southern Babylonian kinsmen, they were artistically talented, as revealed by their masterly sculptures in stone.

Like the Babylonians and Aramaeans, the Assyrians were a Semitic people, speaking a language closely related to that of the Babylonians. They used a modified Babylonian cuneiform script.

Being Semites, the Assyrian religion had many gods in common with other Semitic nations, especially the Babylonians. They too worshiped the great Babylonian deities such as Shamash, the sun god; Sin, the moon god; Ea, the god of waters; and Ishtar, goddess of fertility. However, their principal god was Ashur, who was not part of the Babylonian pantheon. He was depicted as a winged sun that protected and guided the king, who was his principal servant. Ashur was also symbolized by a tree that represented fertility. But above all, Ashur was a god of war, and as such, war therefore intrinsic to the Assyrian national religion. Every Assyrian military campaign was thought to be undertaken in response to the direct orders of Ashur. Thus participation in warfare was considered an act of worship of a kind. Such facts help us understand why the Assyrians were a formidable fighting machine and why the cult of Ashur vanished when the Assyrian Empire was destroyed.

Assyrian Cruelty and Ruthlessness

The Assyrian Empire was the greatest of the Mesopotamian empires. The king, who represented the state, was naturally the pinnacle of the hierarchy, with all public acts recorded as his achievements. His two primary tasks as an Assyrian king were to wage war and erect public buildings. Both were seen as religious duties to the Assyrian gods.

Historians have divided the Assyrian Empire into three periods: the Old Kingdom, the Middle Empire, and the Neo-Assyrian Empire. Most of what follows will concern itself with the greatest period of the Assyrian Empire— that of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (933–612 BC)—the era that primarily gave the Assyrian Empire its reputation for extreme ruthlessness and cruelty. Assyrian history continues past that point, and there are still Assyrians in Iran, Iraq and other countries today. Paradoxically, they are among the most friendly and hospitable people one can meet.

Assyrian national history, as preserved for us in its cuneiform inscriptions and images on walls and floors of palaces and temples, and on clay and alabaster tablets, prisms and cylinders consists mainly of military campaigns and battles. It is perhaps the most gory and bloodthirsty of history known. And from its beginning, Assyria was a strong military power bent on conquest. Any country or people group that opposed their rule was punished with the destruction of their cities and the devastation of their fields and orchards. They were to be feared, with good cause. Adad Nirari I (1307–1275 BC), during the period of the Middle Empire, commenced what would become standard Assyrian policy for the rest of its history: the deportation of large portions of the population of conquered nations and their replacement with Assyrians.

This policy killed the nationalistic spirit and sentiments and destroyed old loyalties of any people groups so treated. It helped prevent further uprisings. While it uprooted people from their own homes and land, they, as labour and persons with knowledge and ability, were extremely valuable to the Assyrians and, it seems, deportees were treated well enough enroute, as attested in a letter from an Assyrian official to his king Tiglath-pileser III (744–727 BC), which reads:

As for the Aramaeans about whom the king my lord has written to me: “Prepare them for their journey!” I shall give them their food supplies, clothes, a waterskin, a pair of shoes and oil. I do not have my donkeys yet, but once they are available, I will dispatch my convoy. (“Mass deportation: the Assyrian resettlement policy,” by Karen Radner)

And upon their arrival, it seems the Assyrians continued to support them, as seen in another letter by the same author:

As for the Aramaeans about whom the king my lord has said: “They are to have wives!” We found numerous suitable women but their fathers refuse to give them in marriage, claiming: “We will not consent unless they can pay the bride price.” Let them be paid so that the Aramaeans can get married. (ibid)

While deportees were carefully selected for their abilities and sent to areas where their talents could be best used, it seems that families were not separated. Rather they were absorbed into the growing empire and accepted as Assyrians.

Under Ashur-Dan (933–910 BC), Assyria conquered northern Mesopotamia. From then on, its armies marched almost every year, ever expanding the Assyrian empire, the booty of their conquests financing their ever-greater exploits and dominion. It was from this time on that the Assyrians began to practice ever increasing cruelty and ruthlessness toward resisting foes.

Assyrian inscriptions and pictorial reliefs testify to the Assyrian treatment of those they conquered, their armies and rulers. For example, Ashurnasirpal II (883–859 BC) calls himself “the trampler of all enemies . . . . who defeated all his enemies [and] hung the corpses of his enemies on posts” (Albert Kirk Grayson, “Assyrian Royal Inscriptions, Part 2,” from Tiglath-pileser I to Ashurnasir-apli II, p. 165).

Accounts like this not only described what actually happened but were no doubt also designed to threaten others who might think of resisting. The following description of another conquest reveals why they could well be called the terrorists of the ancient world:

“In strife and conflict I besieged [and] conquered the city. I felled 3000 of their fighting men with the sword . . . . I captured many troops alive: I cut off some of their arms [and] hands; I cut off others their noses, ears [and] extremities. I gouged out the eyes of many troops. I made one pile of the living [and] one of heads. I hung their heads on trees around the city.” (Grayson, p. 126)

Such Assyrian records, which were only discovered in the past 150 years, also testify to the historical accuracy of ancient Jewish biblical records, as in the writings of the prophet Nahum, who, writing about the inhabitants of Nineveh, the capital of the Assyrian Empire, in 640 BC, records, “Woe to the city of blood, full of lies, full of plunder, never without victims! . . . who has not felt your endless cruelty?” (Nahum 3:1, 19).

The Assyrians and Ancient Israel

It was in this time of barbaric cruelty that the Assyrians first went into battle against Israel. In light of the historicity of such cruelty, one begins to understand the actions taken by some of Israel’s kings and prophets. The first of the Assyrian kings to come in contact with the Israelites was Shalmaneser III (859–824 BC). During his reign, Shalmaneser campaigned in practically every country surrounding his homeland. He records that he fought an alliance of Syrian kings in 853 BC at the battle of Qarqar, in which King Ahab of Israel committed a force of 2000 chariots and 10,000 foot soldiers to the Syrian coalition.

Twelve years later, on the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III, he recorded that King Jehu of Israel gave him tribute. In one of the panels of the Obelisk, Jehu is seen kneeling before Shalmaneser III.

For the next 80 years, several weak rulers led Assyria and the empire lost much of its hold on subjugated nations. However, during this time Adadnirari III (810–782 BC) conquered Damascus from the Syrian king, Hazael, who is mentioned numerous times in biblical records (see 1 Kings 19:15; 2 Kings 10:32). At the same time Adadnirari III conquered Damascus, he mentions on the Tel El Rimah Stele that he received tribute from King Joash of Israel, whose capital was at Samaria. The inscription reads:

Adad-nirari . . . king of Assyria . . . . I gathered my chariots and army and gave them orders to march to the land of Hatti. In just one year, I subdued the entire county of the Amurru as well as Hatti. I imposed upon them tax and tribute forever. I received the tribute of 2000 talents of silver, 1000 talents of copper, 2000 talents of iron and 3000 garments with multi-coloured trim from Mari of the land of Damascus. I also received the tribute of Joash, the Samarian, as well as the rulers of Tyre and of Sidon. (Tell el Rimah stele)

Biblical chronology places the story of Jonah the prophet between (793–753 BC). Given the accounts by the Assyrians of their ruthless cruelty, one can understand Jonah’s reluctance and refusal to go there (see Jonah 1–4). It was an exceedingly dangerous assignment. But he eventually went, proclaiming to them a warning of coming destruction on account of their evil ways. But as the story goes, led by its king, the entire city repented, and so was spared. It is possible that this story occurred during the reign of Adadnirari III, for there is evidence of a monotheistic revolution in which the god Nabu appears to have been proclaimed the sole, or at least the principal, god, occurring in Assyria during his reign.

Under Tiglath-pileser III (745–727 BC), or Pul as he was also known, the Assyrians made an impressive comeback, re-establishing their power over neighbouring nations. He became one of the greatest monarchs and empire builders of Assyria. The Bible records that King Menahem of Israel (of the 10 northern tribes of the Israelites, with its capital at Samaria) paid him tribute:

“And Pul the king of Assyria came against the land: and Menahem gave Pul a thousand talents of silver, that his hand might be with him to confirm the kingdom in his hand.” (see 2 Kings 15:19)

Menahem’s tribute is also mentioned by the Assyrians on the Iran Stele found in Tiglath-pileser’s palace at Calah, which reads:

“I received tribute from . . . Rezon of Damascus, Menahem of Samaria, Hiram of Tyre, . . . gold, silver, . . .” (Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, 283, Ed. James B. Pritchard)

During the reign of King Pekah of Israel, Tiglath-pileser received a request from King Ahaz of Judah (the two southern tribes of the Israelites, with its capital in Jerusalem) to aid him against an alliance between Pekah of Israel and Rezin of Damascus. With the request came a large tribute:

So Ahaz sent messengers to Tiglathpileser king of Assyria, saying, I am thy servant and thy son: come up, and save me out of the hand of the king of Syria, and out of the hand of the king of Israel, which rise up against me. And Ahaz took the silver and gold that was found in the house of the Lord, and in the treasures of the king’s house, and sent it for a present to the king of Assyria. (see 2 Kings 16:7, 8)

And a clay building inscription of Tiglath-Pileser III records the actual payment of this tribute by Ahaz, as follows:

From these I received tribute . . . Ahaz, the king of Judah . . . including gold, silver, iron, fine cloth and many garments made from wool that was dyed in purple . . . as well as all kinds of lavish gifts from many nations and from the kings that rule over them.

Tiglath-pileser also took the practice of deportation to a whole new level of wholesale transplantations of subjugated nations to other countries. On reception of the tribute from Judah, Tiglath-pileser captured and destroyed Damascus, killed Rezin its king, invaded Israel, and deported many of the Israelite captives. This deportation is mentioned in the Bible:

In the days of Pekah king of Israel, Tiglath-Pileser king of Assyria came and took Ijon, Abel Beth Maachah, Janoah, Kedesh, Hazor, Gilead, and Galilee, all the land of Naphtali; and he carried them captive to Assyria. (2 Kings 15:29)

And the following record left by Tiglath-pileser is a direct confirmation of the above account of this deportation:

The land Bit-Humri [House of Omri, which is Israel], all of whose cities I had utterly devastated in my former campaigns, whose [people] and livestock I had carried off and whose [capital] city Samaria alone had been spared: [now] they overthrew Peqah, their king. (Tiglath-pileser III, pp 44, 17, 18)

The land Bit-Humri [Israel]: I brought to Assyria . . ., its auxiliary army, . . . and an assembly of its people. [They (or: I) killed] their king Peqah and I placed Hoshea [as king] over them. (ibid, pp 42, 15b–17a)

Tiglath-pileser allowed a small group to remain as a small vassal state with Samaria as capital. Ahaz king of Judah voluntarily submitted to the Assyrians and Judah became an Assyrian vassal state.

Tiglath-pileser’s successor, Shalmaneser V (727–722 BC) ruled only briefly. During his reign, he fought a coalition of western kings, including Israel, who had ceased to pay tribute. He besieged the Israelite city of Samaria for three years and captured it, probably before his death, leaving the task of deporting the Israelites and resettling their territory with other people groups to his successor, Sargon II, who himself claimed to have conquered Samaria.

Sargon II (722–705 BC) was a strong king who spent much of his reign on military campaigns. He built a new capital at Dur-Sharrukin, today known as Khorsabad, a few kilometres north of Nineveh.

Sargon II’s successor, his son Sennacherib (705–681 BC, made technical improvements to his war machine and rebuilt Nineveh, making it the most glorious city of its time. During his reign, he campaigned in Palestine to put down a rebellion by Hezekiah, King of Judah. This campaign is described in great detail in the Bible, which specifically mentions his capture of the fortified cities of Judah, including his attack of Lachish; the payment of tribute by Hezekiah to Sennacherib; the construction of a water tunnel by Hezekiah; his inability to take the city of Jerusalem; his assassination by two of his sons upon his return to Nineveh; and his replacement by Esarhaddon on the Assyrian throne (2 Kings 18:13, 14, 17; 19:32, 35–37; 20:20).

The biblical account has now been confirmed by archaeology in every detail: the Lachish wall reliefs from Sennacherib’s palace in Nineveh portray the battle of Lachish, as do the excavations of the city of Lachish; Hezekiah’s water tunnel in Jerusalem, which begins at the Gihon Spring and ends at the Pool of Siloam, has been discovered; an inscription on the flank of an Assyrian human-headed winged bull informs us that Hezekiah paid taxes to Sennacherib; the Taylor Prism of Sennacherib informs us of the 46 cities of Judah that he captured—but interestingly when it comes to the city of Jerusalem, Hezekiah simply says that he “shut up Hezekiah like a bird in a cage.” We also know that on his return to Nineveh, Sennacherib was assassinated and that Esarhaddon did take his place on the throne. Such discoveries confirm the Bible a legitimate and accurate historical source and one not be dismissed.

According to Austen Henry Layard, the excavator of Nineveh, the wall reliefs in Sennacherib’s palace would stretch more than three kilometres (2 miles) if lined in a row. Included among these reliefs are those depicting the barbaric flaying (skinning alive) and impaling of Israelite captives of Lachish.

But Sennacherib’s wall reliefs and inscriptions also demonstrate that he surpassed his predecessors in the grisly detail of his descriptions, an indication no doubt that he literally took Assyrian ruthless cruelty to a new level, if that were possible:

I cut their throats like lambs. I cut off their precious lives [as one cuts] a string. Like the many waters of a storm, I made [the contents of] their gullets and entrails run down upon the wide earth. My prancing steeds harnessed for my riding, plunged into the streams of their blood as [into] a river. The wheels of my war chariot, which brings low the wicked and the evil, were bespattered with blood and filth. With the bodies of their warriors I filled the plain, like grass. [Their] testicles I cut off, and tore out their privates like the seeds of cucumbers.” (Daniel David Luckenbill, Ancient Assyrian Records of Assyria and Babylonia, Vol. 1, sections 584, 585)

With the discovery of such gruesome details, one can clearly understand why Hezekiah, on receiving a letter from Sennacherib at Lachish, as the story is told, took it into the temple, lay it out before God and prayed for help (2 Kings 19:14–19).

While Esarhaddon (681–669 BC), his son and successor, conducted a successful military campaign against Egypt, which thus pushed the boundaries of the Assyrian Empire to its furthest extent, nothing changed with respect to Assyrian ruthlessness. In fact, he seems to have been even more macabre in his treatment of his enemies than his father and grandfather:

“Like a fish I caught him up out of the sea and cut off his head,” he said of the king of Sidon; “I hung the heads of Sandurri [king of the cities of Kundi and Sizu] and Abdi-milkutti [king of Sidon] on the shoulders of their nobles and with singing and music; I paraded through the public square of Nineveh.” (Lukenbill, Vol. 2, sections 511, 528)

The biblical prophet Nahum, writing around 640 BC, could not have been more accurate in calling Nineveh “the city of blood” (Nahum 3:1).

Finally under his son, Ashurbanipal (669–627 BC, Assyria reached the zenith of its glory and extent but at the same time the greatest depths of its depraved cruelty. Boasted Ashurbanipal:

“Their dismembered bodies I fed to the dogs, swine, wolves and eagles, to the birds of heaven and the fish in the deep . . . . What was left of the feast of the dogs and swine, of their members which blocked the streets and filled the squares, I ordered them to remove from Babylon, Kutha and Sippar, and to cast upon heaps.” (Lukenbill, Vol. 2, section 800)

But no civilization given to such brutality can expect not to disintegrate. The noted English historian, Sir Arnold J Toynbee, analysed the histories of 21 civilizations, including ancient Rome, Babylon, the Greeks and the Aztecs. In his epic A Study of History he describes six characteristics of civilizations on the brink of collapse—the first of which he terms a “schism of the soul,” in which a society commits a type of cultural suicide, where something down deep inside of the corporate psyche of society snaps, and by which a civilization thereby self-destructs by destroying its own soul. An example of this is what took place in the amphitheatres of ancient Rome, where for entertainment citizens spent their leisure hours watching humans slaughtered, slashed, gutted and gored. The lust for violence and blood of the Assyrian terrorists of the ancient world is perhaps an even greater example.

Accordingly, the ancient biblical prophets made pointed predictions against Assyria, especially concerning Nineveh, its capital. While it was still at its peak, they predicted with astounding accuracy that drunkenness, flood and fire would be part of its destruction, that it would be laid waste and become a desolation (see Nahum 1:8, 10; 3:7, 13, 15; Zephaniah 2:13).

According to the ancient historian, Diodorus, during the siege of Nineveh, the nearby river flooded and destroyed a section of the wall, through which the Babylonians and Medes gained access to the city. Temples were sacked and the palace was burned. Evidence of such a burning can still be seen on the blackened wall reliefs in the British Museum that were taken from the palace of Nineveh.

Little wonder, then, that at the destruction of Assyria and its mighty capital Nineveh, the nations rejoiced, as expressed by Nahum: “Everyone who hears the news about you claps his hands at your fall” (Nahum 3:19).

Warnings from Terrorists of the Ancient World

There are ominous warnings for today to be found in the ancient Assyrian empire’s barbarism. First, Assyria’s ruthless cruelty was primarily a result of its religious belief that war was an act of worship. It would not be an overstatement to characterise Assyria’s relentless cruelty as religious terrorism akin to that being played out in Syria, Iraq and other countries by ISIS today. It should warn us of the danger of religious movements who seek to unite the state with religion. Such a combination, throughout history, inevitably led to intolerance and eventual persecution.

As serious and as real as this threat is, there is an even more prescient warning against a contemporary and more sinister threat to be had—our contemporary global lust for the violence and mayhem on the Hollywood silver screen, where we see humans butchered, blown up and variously killed. We might well learn from the history of ancient Assyria and its modern counterparts in light of Toynbee’s first characteristic of a civilization in disintegration—cultural suicide through a “schism of the soul.”

Sources

-

Albert Kirk Grayson, “Assyrian Royal Inscriptions,” Part 2, in Tiglath- pileser I to Ashurnasir-apli II.

-

Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament 283. Ed. James B Pritchard

-

Diodorus ii. 26,27

-

Dwight Nelson, “Why Civilizations Fall,” Program 3, Net 98, 1998

-

Erika Belibtreu, “Grisly Assyrian Record of Torture and Death,” in Biblical Archaeology Review, 17:01 (Jan/Feb 1991)

-

Joshua J. Mark, “Assyria,” in Ancient History Encyclopaedia, June 12, 2014, http://www.ancient.eu/assyria

-

Karen Radner, “Mass Deportation: the Assyrian Resettlement Policy” (http://www.ucl.ac.uk/sargon/essentials/governors/ massdeportation/)

-

Karen Radner, “Israel, the ‘House of Omri,” Assyrian Empire Builders, University College London, 2012 (http://www.ucl.ac.uk/sargon/ essentials/countries/israel/)

-

Daniel David Luckenbill, Ancient Assyrian Records of Assyria and Babylonia, Vol 1 & 2

-

Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary Vol. 2, p. 60.

-

Seventh-day Adventist Bible Dictionary Vol. 8, pp. 91–94; p. 464