Of all Jewish archaeologists, Nelson Glueck is rightly ranked among the best. Throughout a career that spanned some four decades, Glueck made many important archaeological discoveries in and around Israel. These discoveries were especially important to Bible believers because of the support they give to the biblical record, so often called into question. As a consequence, many archaeologists were prompted to take the Bible narrative and history as a source of factual information.

Nelson Glueck was born on June 4, 1900, in Cincinnati, Ohio, to merchant parents Morris Glueck and Anna Rubin, both German Jews. From very early in life, Nelson was attracted to his parents’ Jewish faith; he loved to read the accounts of his ancestors contained in the Jewish Scriptures—the Old Testament of the Christian Bible—an attraction that turned into passion, which turned into a career. But first he was ordained a Jewish rabbi at the relatively young age of 22.

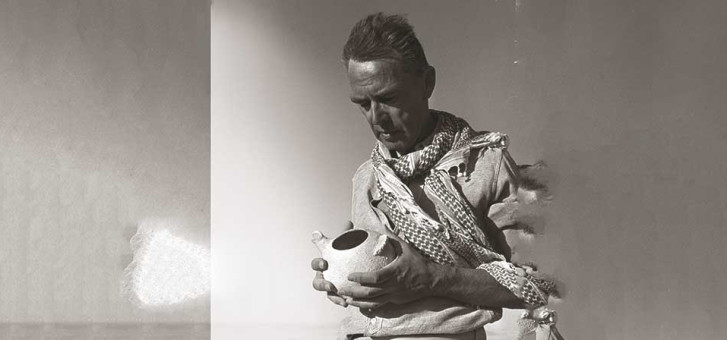

Excavating in Jordan. In 1937, Glueck discovered this sculpted stone panel of a vegetation goddess at Khirbet et-Tannur, 70 km (43 miles) north of Petra. It originally decorated the entrance to a Nabataean open-air sanctuary. Posing behind the sculpture, from left, are fellow archaeologists Clarence Fisher, Carl Pape, Glueck’s wife Helen, Nelson Glueck and S J Schweig.

Excavating in Jordan. In 1937, Glueck discovered this sculpted stone panel of a vegetation goddess at Khirbet et-Tannur, 70 km (43 miles) north of Petra. It originally decorated the entrance to a Nabataean open-air sanctuary. Posing behind the sculpture, from left, are fellow archaeologists Clarence Fisher, Carl Pape, Glueck’s wife Helen, Nelson Glueck and S J Schweig.

Not one to rest on his laurels, he studied relentlessly and in 1926 received a PhD from the University of Jena in Germany.

But it was when Nelson visited the “Holy Land” soon after receiving his PhD that his career as an expert on the Bible took off. He became intimately connected and familiar with the Holy Land and the artefacts of the various civilisations that had once thrived in the Ancient Near East millennia before. Interestingly, his knowledge of the region was so extensive that during World War II he was employed by the US Office of Strategic Services to devise a plan of retreat for Allied forces before the advance of German Field Marshal Rommel and his army.

After the war, Glueck returned to his two main loves: the study of the Bible and of the Holy Land. Throughout the 1950s, Glueck carried out a number of important excavations and field studies. In the process he became the first archaeologist to identify Edomite, Midianite and Negevite pottery, and also rediscovered the Nabataean civilisation of Jordan.

Although themselves quite incredible finds, what made them invaluable was that the peoples are mentioned in the Bible. This moved Glueck profoundly, and so much so that he said, “It may be stated categorically that no archaeological discovery has ever controverted a Biblical reference. Scores of archaeological findings have been made which confirm in clear outline or exact detail historical statements in the Bible. And, by the same token, proper evaluation of Biblical descriptions has often led to amazing discoveries.”

There is no doubt that Glueck’s discoveries encouraged and built his faith, enhancing his trust in the Bible. But he was always careful to never replace the Bible’s spiritual meaning with mere historical analysis. In his words, he tried never to “confuse fact with faith, history with holiness, science with religion.”

Glueck on Time. The December 13, 1963 Time magazine featured Nelson Glueck on the cover and provided a fascinating review of many of Glueck’s archaeological finds and research projects in the Holy Land.

Glueck on Time. The December 13, 1963 Time magazine featured Nelson Glueck on the cover and provided a fascinating review of many of Glueck’s archaeological finds and research projects in the Holy Land.

Such was his reputation that he was invited to deliver the Benediction at US President John F. Kennedy’s inauguration in 1961, an invitation he gladly accepted. Two years later, his image graced the December 13, 1963 cover of Time magazine along with the captions, "Archaeologist Nelson Glueck" and, "The Search for Man’s Past."

Over the post war years, Glueck would go on to become friend and adviser to the early leaders of the young state of Israel, including David Ben-Gurion, Abba Edan, Golda Meir, Henrietta Szold and Judah Magnes. But for all of Glueck’s political commitments, he never stopped researching and writing on biblical archaeology, publishing such titles as Exploration in Eastern Palestine (in 4 Volumes, 1934-51), The Other Side of the Jordan (1940), The River Jordan (1946), Rivers in the Desert: A History of the Negev (1959), Deities and Dolphins (1965), and Hesed in the Bible (1968).

Solomon’s Pillars. Glueck investigated the copper mines of Timna, Israel, in the 1930s, believing he’d found “King Solomon’s mines.” He gave these 50-metre- (165 ft) high sandstone walls carved by erosion the name “Solomon’s Pillars,” helping to promote the now national park.

Solomon’s Pillars. Glueck investigated the copper mines of Timna, Israel, in the 1930s, believing he’d found “King Solomon’s mines.” He gave these 50-metre- (165 ft) high sandstone walls carved by erosion the name “Solomon’s Pillars,” helping to promote the now national park.

It is fair to say that Glueck’s enthusiasm for archaeology stemmed from his love for the Bible, which began as a child. But it is also true that Glueck’s love for the Bible was, in turn, encouraged and strengthened by his archaeological discoveries in and around Israel. As he himself wrote: “Above all, read the Bible, morning, noon and night, with a positive attitude, reading to accept its historical references . . . . And then go forth into the wilderness of the Negev and discover, trite as it may sound, that everything you touch turns into the gold of history.”

What interested Glueck in that “gold of history” were the stories that artefacts can tell us about real people who lived thousands of years ago, and their traditions which are still kept alive among many cultures today. Through understanding and immersing himself in such ancient cultures and customs of the Middle East, and through learning their histories and their place in the Bible, Glueck believed that this made for better archaeological practice in the region. As he put it, “Acquaint yourself with the needs and fears, the moods and manners, of the broken array of peoples and civilizations that appeared at intervals along the horizon of time and, in a general way, you will know in advance where to look for the clues they left behind in the course of their passage.” And thus, in a roundabout way, many of us would understand that through reading the Bible hungrily, Glueck was better able to understand all of humanity and his own place within it, something many archaeologists still seek.

Nelson Glueck died in Cincinnati on February 12, 1971, aged just 70 years, survived by his wife, Helen Iglauer, and their son, Charles Jonathan. The Nelson Glueck School of Biblical Archaeology at the Hebrew Union College in Jerusalem, which Glueck founded in 1963, continues his legacy, conducting research programs throughout Israel to this day.