If true leaders are those who can solve multiple problems at a stroke, then Vespasian must rank among the best of them. Although born into a family of modest means on the November 17, AD 9, in the small Italian town of Falacrina, Vespasian was destined for greatness. After becoming a soldier, he served in Thrace, Crete, Cyrene, Germany, Britain and Africa, rising through the ranks. Such was his no-mess reputation among Roman armies, that when the Jews of Judea rebelled against Rome in AD 66, the emperor of the day, Nero, appointed Vespasian as commander of the legions of the East to deal with the war.

As commander in Judea, Vespasian’s soldiers captured the enemy general Flavius Josephus, who would come in very handy to Vespasian later. But then came Nero’s suicide and the proclamation of a new emperor, Galba. Like Vespasian, Galba was military, in charge of Rome’s army in Spain. But unlike Vespasian, he came from a very wealthy family. According to Galba’s biographer Plutarch, Galba despised Nero’s proneness to luxury and debauchery and in late AD 68 he marched on Rome with a view to restoring Rome’s traditionally more sober and humble way of life (Plutarch, Galba, 16). When he arrived in Rome, Galba was welcomed with much fanfare, and when the Roman Senate declared Galba emperor, it appeared that Rome had finally found itself a ruler whose experience with the armies in the provinces had provided him with wisdom.

Unfortunately, that was the beginning of Rome’s troubles. When he became emperor, Galba was already in his seventies. So, on account of his age, Galba was forced to name an heir. But when he overlooked his general and close adviser, Otho, for another person, Piso, Otho, who fancied himself as another Nero, was enraged. According to Roman historian Tacitus, Galba chose Piso over Otho because Piso was more of a traditionalist, whereas Galba felt it futile to seize power from Nero in order to pass it on to another one like him (Tacitus, Histories, 1. 13). But Otho soon secured the support of Nero’s bodyguard, the Praetorian Guard, who wanted to see a return to the good times and lavishness of a Nero-like Otho. With their help, Otho had Galba assassinated and he took over the imperial throne for himself.

While these events were unfolding, to the north the clouds of war were approaching. In the Rhineland, the Roman governor, Vitellius, had been proclaimed emperor by his loyal legion. Suetonius, the biographer of Vitellius, describes him as a cruel individual prone to vice such that he became a willing servant to Tiberius, while he indulged himself in his later years on the island of Capri and a friend to Caligula while he spent time on that island (Suetonius, Vitellius, 4). Vitellius sent his armies to fight Otho, but Otho, like Nero his idol, chose suicide. Vitellius was now emperor.

All the while, Vespasian had been leading Rome’s legions in a war against the Jews of Judea. Later, Flavius Josephus would write that when it became known there that Vitellius had become emperor, Vespasian’s own soldiers began to compare Vitellius, who styled himself as yet another ruthless and self-indulgent despot, with their own leader Vespasian, who had a practical wisdom about him. He also had two loyal sons, Titus and Domitian, who could smoothly transition as imperial successors, and without struggle when Vespasian eventually died. On July 1,AD 69, aged 59, Vespasian was proclaimed emperor by his officers and troops who then begged him to lead them on to Rome (Josephus, The Jewish War, 4. 577–603).

Vespasian soon found that other parts of the empire were rallying to his cause, and he ordered the armies of the Danube frontier to march on Rome with a view of ousting Vitellius and establishing himself as emperor.

Meanwhile, Vespasian took control of Egypt, which supplied much of the grain for Rome, leaving the reduction of Judea to his son Titus, which he completed within a year. Thus, with one broad stroke, Vespasian had cut off the food supply to Vitellius’ army, put an end to the Jewish War and rallied far-flung troops for a march on Rome. The writing, for Vitellius, was on the wall: he was up against a consummate strategist and tactician. Fight as they might, Vitellius’ armies were quickly defeated, with Vitellius killed by a Roman mob in the heart of the city. Vespasian’s position as emperor of the Roman Empire was now secure.

But after a year of civil unrest and civil war, the empire Vespasian now ruled was weakened and tottering. Italy was stripped of its produce, Rome’s armies were depleted and Judea was in ruins. Almost 100,000 Jews had been sold into slavery; so many that prices plummeted. Most of the Jewish slaves were sent to mines of Egypt, with many of the rest distributed to the amphitheatres of Italy, to die as entertainment for the masses (Josephus, The Jewish War, 6. 382–385, 418–423), including that of Pompeii, a popular tourist attraction today.

Vespasian took it upon himself to rebuild this fraying empire. Although he had gained much loot from his victory in Judea, the imperial purse was empty. According to Suetonius, Rome’s treasury was some 40 billion sesterces in debt (Suetonius, Vespasian, 16), although many modern historians revise this to just 4 billion sesterces. To give this some context, Rome’s annual intake from taxes was 800 million sesterces. Vespasian was necessarily frugal, spending only on sustainable projects. He invested in education and the arts, and began building Rome’s most iconic empirical structure, the Colosseum. He also invested in peace. A Temple of Peace was rapidly constructed near the Roman Forum, such that it could be said that its builder genuinely believed in the necessity for peace and, conveniently now that he was in power, an end to civil war.

But just as things began to improve, events in the east threatened this peace. Caesennius Paetus, the Roman governor of Syria, received news that Antiochus, king of the Roman client state of Commagene in present-day eastern Turkey, intended to defect to the Roman nemesis, the Parthians. Immediately and recklessly Paetus invaded Commagene, at the head of his Sixth Legion. Antiochus fled with his wife and daughters for Cilicia. But his sons Epiphanes and Callinicus remained behind and joined battle with Paetus.

A podium dedicated to Emperor Vespasian in the city of Side, Turkey. After losing function as a podium, it was moved and converted to a fountain.

A podium dedicated to Emperor Vespasian in the city of Side, Turkey. After losing function as a podium, it was moved and converted to a fountain.

The battle lasted a whole day, but eventually the Sixth Legion proved itself victor. Epiphanes and Callinicus fled to the Parthian king’s court, where King Vologases welcomed them. The world teetered on the brink of another all-out conflict between rival superpowers, the Roman and Parthian empires. But then Vespasian intervened, sending an offer of safe conduct for Antiochus and his two sons to Sparta in Greece. To the defeated, the offer was too good to refuse, and the two returned to their family and lived at peace in Sparta according to the promise made by Vespasian.

Three 14.2-metre- (46.5 feet) high Corinthian columns are all that remain of the temple Domitian dedicated to his father, the deified emperor Vespasian, and his brother Titus, at the west end of the Roman Forum, in AD 87.

Three 14.2-metre- (46.5 feet) high Corinthian columns are all that remain of the temple Domitian dedicated to his father, the deified emperor Vespasian, and his brother Titus, at the west end of the Roman Forum, in AD 87.

Such goes the story, all recorded in ancient sources: two Latin inscriptions from Baalbek in Syria prove the story true. The first mentions, among other things, the “[bello] Co[m]magenico,” or “Commagene War” that Paetus led (ILS 9198), while the second commemorates the soldier who carried Vespasian’s message to Epiphanes and Callinicus when exiled in the Parthian court and who then escorted them through to Roman territory to Greece. Translated, it reads:

“To Gaius Velius Rufus son of Salvius . . . . He was sent into Parthia and brought back to Vespasian Epiphanes and Callinicus, the sons of king Antiochus [of Commagene], together with a large number of tribute-paying persons.” (ILS 9200)

As for Paetus, Vespasian couldn’t afford to leave him in charge of his army in the east. After all, Vespasian had seized the empire from just such a position and further, it was Paetus who, by his reckless invasion of Commagene, had almost started a war with Parthia. So, he was removed by Vespasian and replaced with Traianus, the father of Trajan who would one day ascend to emperor of Rome

Traianus was a trusted deputy of Vespasian, and he had taken a leading role in the Jewish War under both Vespasian and then his son Titus. In fact, he had often led the vanguard in attack. We also know that he was a staunch supporter of Vespasian’s cause throughout the civil wars ofAD 69. In March 1973, a Roman milestone was discovered near Afula in Judea, inscribed with a message by Traianus.

In essence, the inscription says that Traianus, as legate of the Tenth Legion supported Vespasian as Augustus, or emperor. Given that the inscription lacks official titles as bestowed upon Vespasian as emperor, then Traianus must have made the inscription before Vespasian’s final victory while the Jewish War and the civil war ofAD 69 still raged. It is illustrative of Traianus’ total allegiance to Vespasian. It is little surprise then that Vespasian placed his trust in Traianus to take Paetus’ place as governor of Syria and commander of most of Rome’s armies in the east. By simply removing Paetus and appointing Traianus, Vespasian had once again, characteristically, solved the east’s problems with little effort.

But these were still only temporary solutions. Soon a new crisis emerged in the east that required Vespasian’s full attention. InAD 75, the Alani, a nomadic Scythian horde from central Asia, burst into the Parthian Empire from the east of the Caspian Sea, devastating Parthian lands as they progressed along the southern Caspian and into present day Armenia, plundering as they went. Devoid of ideas and the means of halting their progress, Parthian King Vologases sent an urgent request to Vespasian for help. According to Suetonius, Domitian begged his father to allow him to take charge in the war against the Alani but Vespasian flatly refused (Suetonius, Domitian, 2). It wasn’t the Alani that Vespasian wanted to conquer but Rome’s traditional rivals, the Parthians. As a result, Vespasian courteously replied to Vologases—according to Cassius Dio—that “it was not proper for him to interfere in other’s affairs” (Cassius Dio, 65. 15. 3). This was counter-intuitive: Vespasian had interfered in the state affairs of others his entire life. As a soldier in Rome’s armies, he was not averse to it in the slightest.

Details of exactly what happened next are lost, but from fragments of information, it is possible to reconstruct the general picture. We know from a commemorative inscription written in Greek, set up by king Mithridates of Armenia at precisely this time in Harmozica (Armenia) itself, that Vespasian had a hand in political affairs there, making the Armenian King Mithridates openly declare himself to be a philocaesar and philoromaion, or “friend of Caesar” and “friend of the Romans” (ILS 8795). But there’s more.

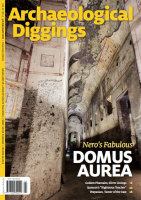

The Roman Colosseum, originally known as the Flavian Amphitheatre, was commisioned in AD 72 by Emperor Vespasian. It was completed by his son, Titus, in 80, with later improvements by Domitian. Vespasian ordered the Colosseum to be built on the site of Nero’s palace, the Domus Aurea, to dissociate himself from the hated tyrant.

The Roman Colosseum, originally known as the Flavian Amphitheatre, was commisioned in AD 72 by Emperor Vespasian. It was completed by his son, Titus, in 80, with later improvements by Domitian. Vespasian ordered the Colosseum to be built on the site of Nero’s palace, the Domus Aurea, to dissociate himself from the hated tyrant.

It appears that Vespasian had despatched troops to the southern Caspian region at this time as well. An inscription near Baku on the Apsheronsky Peninsula on the Caspian Sea dated to Domitian’s reign (AD 81–96), shows that Vespasian had had a hand in military affairs there too. The Latin inscription states that the XII Fulminata Detachment of the Seventh Legion had been stationed there for some time (McCrum and Woodhead (1966) Number 369). Furthermore, we learn from Pliny the Younger that at precisely this time, Traianus received honorary triumphal decorations from Vespasian for a military victory over the Parthians (Pliny the Younger, Panegyricus, 9, 14, 16). The picture becomes clear: behind the niceties of international diplomacy, subtle and complex moves were undertaken to undermine Parthia’s power in the Middle East. Out of sight, Vespasian had apparently instructed Traianus to deploy along the Alani line of march and support them in their war with Parthia, a war that proved extremely successful. It is testament to Traianus’ carrying out of these instructions that he was rewarded by Vespasian upon its completion. Thus, in one sweep of the hand, Vespasian had supplied Rome with a foreign victory, something always appreciated by the Roman populous, and idealised Traianus as the model Roman loyalist who was duly rewarded for his allegiance. The message was clear and promoted peace and loyalty throughout the empire, all with little cost to the imperial purse.

The works of Flavius Josephus, a 1785 translation of the first-century Romano-Jewish historian’s work. To avert war, Vespasian employed Josephus to write an account of the Jewish War to convince dissenters that Rome was not to be messed with.

The works of Flavius Josephus, a 1785 translation of the first-century Romano-Jewish historian’s work. To avert war, Vespasian employed Josephus to write an account of the Jewish War to convince dissenters that Rome was not to be messed with.

However, once the Alani had eventually withdrawn from Parthia’s lands, Vologases seethed with hate for Rome. Rome could still ill-afford a full-scale war with Parthia, so Vespasian employed Flavius Josephus, that Jewish general he’d captured years before, to write an account of the Jewish War, first in Aramaic, then in Greek, to be read throughout the Middle East to persuade readers not to fight against the might of Rome. Josephus the general then became Josephus the historian, producing The Jewish War, a work which in Josephus’ own words was written to inform the “Parthians, Babylonians, Southern Arabians, Mesopotamian Jews, and Adiabenes . . . of the causes of the war, the sufferings involved and its disastrous ending [for the Jews]” (Josephus, The Jewish War, 1. 1–7).

This work then launches into the glories of the Jewish nation, especially under Herod the Great, describing how Rome’s armies under Vespasian and Titus dismantled it through war as a result of its revolt. The propaganda worked, with Josephus’ writings becoming popular among the educated elites of the Middle East. As a consequence, war was averted, with Parthia accepting that Rome was not to be messed with.

Vespasian was a consummate strategist, of that there is little doubt. But to the very end of his life, he remained a soldier’s soldier, emperor of armies. In AD 79, dying, aged at 69, his soldier’s humour remained intact. Suetonius records that Vespasian joked about the Roman practice of deifying emperors once they died, saying on his death-bed, “Dear me! I must be turning into a god” (Suetonius, Vespasian, 23).

Vespasian had crushed rebellion, emerged victorious in civil war and strengthened Roman interests in the Middle East. In doing so he had shown that with determination, any Roman of humble origins could serve the interests of the empire well, whether as a soldier or a leader, so long as he had intelligence and ability. Vespasian’s reign is considered one of stability for the Roman Empire. Yes, there were periods when the peace was tested, yet through his taming of the east, Vespasian had shown he was up to the task of ruling, bringing about a return to its former glory—glory that would be the inheritance of his son and imperial successor, Titus.