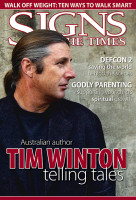

With seven novels, two non-fiction books, three books of short stories and seven children's books, Tim Winton is well established as one of Australia's foremost living writers. But Winton has made his name not just as a writer who is Australian but as a genuinely Australian writer. Most of his stories and characters are drawn from the ordinary experiences—and often the darker and more poignant aspects of these experiences—set in the unique places of Australia.

Growing up in suburban Perth and coastal Albany, Western Australia, Winton now lives much of the year in Fremantle.

He is married with three children and, a continent away from the publishing and arts communities of Sydney and Melbourne, maintains an unassuming life by the standards of his internationally acclaimed literary career.

“When you come from where I do, you know when you get published you're good,” he reflects. “You're from the wrong hemisphere, wrong country, wrong part of the wrong country.” Rather than a string of literary friendships, most of Winton's closest friends live and work in the suburbs in which he lives and works. “I want to meet other people. When writers get together they just sit around and moan about their publishers and moan about reviews. Life is just too short for that,” he comments.

“Life's more important than art. You need art to be a part of life but it isn't life. If you live a life where you mistake one for another then you're in strife.

Do you want to go to your deathbed wishing you'd got a better review in the New Yorker or do you want to be thinking about what sort of parent you've been to your kids?” According to Winton, who turns 47 this year, he always wanted to be a writer. “Now I'm puzzled as to how I knew,” he reflects. “I was certain then and I've understood it my whole life, but the older I get, the scarier I find that certainty that I had. I mean, what did I know at 10? “I'd never met a writer until I was in university. I just had this strange sense that I wanted to do this very particular thing and I spent the rest of my life narrowing down my options so that I couldn't do anything else.” At 19, while a student at Curtin University, Winton won the Vogel Award for an unpublished author with An Open Swimmer and still wider recognition just three years later with his second novel, Shallows , winning the Miles Franklin Award in 1984. He has repeated his win in Australia's most prestigious prize for literature with Cloudstreet in 1991 and Dirt Music in 2002.

He has also received a string of awards and shortlistings around Australia and internationally.

“You get a little bit of affirmation [from literary awards], which is nice,” he says. “But you can't take it too seriously because if you win it doesn't mean necessarily that yours is the best book. If you lose it doesn't mean yours isn't the best book.” Winton has a similarly pragmatic approach to how he goes about his writing. He keeps what he has described as “union hours” at his desk.

“I just rock up to the desk in the morning and hope something shows up,” he says. “I figure if I don't show up then nothing else could show up, or it could show up and I'm not there, in which case there's a day gone.

“There are some days when you just can't believe your luck and other days where you know it's just not going to rain for five years. It's a strange way to live a life where you have to live by your wits “There's a kind of discipline in going to the empty desk, the empty page— and waiting. Once I achieve a certain kind of momentum, then I'm OK. But it's sort of getting up to warp speed that takes me a lot of energy.

“I just write by hand. I don't know how to describe it, really. The process is not very intellectual. It's not very rational. I don't plan things. I'm just trying not to be bored.”

Writing in and about such distinctly Australian settings, Winton admits he is somewhat surprised—and pleased— at the appeal of his books around the world. “They respond to it emotionally and they respond to it in terms of what they call the music of the prose,” he explains. “If I get a letter from Poland or Finland, Norway or Italy, it's always wonderful. Every reader is a miracle.

And welcome.” According to Winton, his first appreciation of storytelling was in the context of family gatherings. “I would hear the voices, you know, the way that people were talking,” he says. “And that for me was kind of musical. I liked the way that people would tell the stories, but the way that they told it was great, the musicality of it and the kind of old language that they were using. That was nice.” He also recalls overhearing his parents' late-night conversations when his policeman father would tell the stories of his working day. “I ended up finding out a lot more about my mates' parents than I ever expected to know,” he says.

“Because I was from a really sort of sheltered, loving, warm environment, I was sort of protected from a lot of stuff.

This other stuff came to me through the asbestos wall and introduced me to other peoples' lives. I didn't realise how other people lived, you know, that their dads bashed them or that their mothers were frightened or that their brothers were junkies.

“When Dad thought we were safely asleep, I'd be listening through the wall and hearing Dad off-load this kind of stuff. I guess it had a real effect on me.

I mean it was good for stories if you turn out to be a novelist, but somehow you have to absorb that stuff.

And I realised there was so much damage out there and people were living other kinds of lives. I guess it fuelled my imagination and I think it gave me more sympathy for other people.” These stories, this sense of humanity and Winton's experiences growing up on the rugged West Australian coast have provided much of the raw material for his novels. But another influence is his faith that finds expression in the moments of redemption and hope portrayed in the stories and in characters who try to live their lives with a higher perspective—“kind of finding our way,” as one of the characters in The Turning puts it.

Winton told the story of the experience that sparked his faith to Andrew Denton in an interview on ABC TV's Enough Rope in 2004: “My dad was a motorcycle cop—a traffic cop—and he was knocked off his motorbike by a drunk driver, and he went through the wall of a factory,” Winton narrated.

“He was in a coma for weeks and weeks. I remember the day that they brought him home and he was sort of like an earlier version of my father, a sort of augmented version of my father.

He was sort of recognisable but not really my dad. Everything was busted up and they put him in the chair, and, you know, ‘Here's your dad.' And I was sort of horrified.

“And Mum had real difficulty, because he was a big bloke. And even though he was a little withered by the time in hospital, it was really difficult for her to bathe him.

“And I remember one day this bloke showed up at the front door. He just banged on the door and said, ‘Oh, G'day. My name's Len. I heard your hubby's a bit crook. Anything I can do?' “He just showed up, and he used to carry my dad from bed and put him in the bath and he used to bathe him, which in the '60s in Perth in the suburbs was not the sort of thing you saw every day.

“It turned out that this bloke, Len Thomas, was from a local church and he'd heard that the old man was sick, and he thought he'd come and help out. This was a weird, kind of strangely sacrificial act, where he'd come and wash another grown man and carry him to bed and look after him in a way that Mum just physically couldn't. It really touched me, regardless of theology or anything else, watching a grown man bother, for nothing, to show up and wash a sick man.

“It really affected me—and gave me some stories.”

Sources: Enough Rope , ABC TV; Paul Daley, “Tim Winton's big issues,” Sydney Morning Herald .