After his father had invaded Babylonia in 1158 BC, King Kutir-Nahhunte of the ancient kingdom of Elam (in what is now Iran) dealt a crushing blow to the Babylonians. The king plundered the ancient Mesopotamian city and took a statue of the god Marduk from its temple with him to Elam. To the Babylonians, this was not just the theft of a prestigious cultural object, but rather it was the literal abduction of their patron god.

In ancient Mesopotamia, the statues of gods were not representations of deities; they were the deities. The temples into which the Mesopotamians placed the statues of their gods were literally considered to be the god’s house on earth. While in their homes on the physical realm, the statues imbued with the spirits of gods had to be clothed in jewels and fine cloth, sacrificed to, worshipped, entertained with dance and music and even fed rich foods and delicacies. Therefore, when Kutir-Nahhunte abducted Marduk, he was making a powerful statement to the Babylonians that their god had deserted them, and thus they deserved any negative consequences that occurred afterwards, such as natural disasters, famine and plagues.

Kutir-Nahhunte was not the first king of the ancient Near East to abduct the god of a conquered foe, nor would he be the last. Centuries before the reign of Kutir-Nahhunte, at the end of the Third Dynasty of Ur, the Gutians stole the statue of Nanna, the patron deity of the city. When Dadusha, the ruler of the ancient Mesopotamian city of Eshnunna, fought a war against his rival, Bunu-Ishtar, he conquered the cities of Tutarra, Halkum, Hurara and Kirhum. As he plundered each city, Dadusha made sure to take all of the statues of their gods back with him to Eshnunna. The Assyrian king Tukulti-Ninurta I had even taken the statue of Marduk in 1225 BC, only to have it returned to Babylon years later by one of his successors.

The abduction of a god was the most devastating insult a king could inflict upon an enemy, while if a king could reclaim his stolen deity, his prestige would increase considerably. When the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar I invaded Elam to reclaim the statue of Marduk nearly 35 years after it was taken by Kutir-Nahhunte, he became a legend and one of the most important Babylonian rulers ever to reign. Due to the belief an abducted god meant his desertion from his homeland, a defeated king could also diminish some of his own humiliation. Many ancient Mesopotamian rulers claimed the abducted god taken by their enemies was not worshipped properly or sufficiently enough by the populace, which led to the god abandoning the people. Therefore, if a king lost a battle, he could claim it was not because of his own incompetence but rather the failure of the people to please their god.

The belief in ancient Mesopotamia that the gods were the most important aspect of society certainly did not just relate to their role in warfare and had been established very early in the history of the region. According to the famous law code of the ancient Babylonian ruler Hammurabi (1792–1750 BC), if a crime directly, or even indirectly, related to a god or a temple, the punishment was incredibly more severe. For example, if any sort of possession were stolen, especially livestock, the thief would have to repay 10 times its original value to the owner. However, if that possession belonged to a god or a temple, the punishment was increased to 30 times its value. The theft of property belonging to a god or temple would result in the most severe punishment—the execution of the thief. This punishment even extended to those who later purchased stolen property from a god or temple, resulting in the death of the customer even if he did not know he had purchased something stolen.

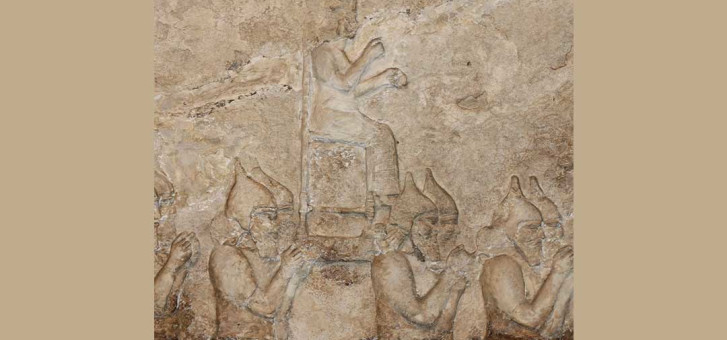

For much of the history of the ancient Near East, the heart of the Mesopotamian world was in the south, centred on the city-state of Babylon. Much of the culture of the region developed there first and then quickly spread throughout the rest of the area, including architecture and the cuneiform writing system. Because of this, it was vital for the surrounding kingdoms like Elam and Assyria to assert their dominance over Babylon and the various other city-states in Mesopotamia in order to legitimise their ascendency in the region. The Assyrians were arguably the most successful at this due to the military achievements of their rulers, especially during the Neo-Assyrian era. Centuries after Tukulti-Ninurta I had abducted the statue of Marduk, a relief was created in the eighth century BC showing the Neo-Assyrian soldiers of Tiglath-pileser III (744–727 BC) taking statues of the gods from Nimrud. When conflict erupted between Assyria and Babylon in the seventh century BC, the religious centre of Sippar, located on the border between the two states, was caught in the middle. As a result, the Neo-Assyrian ruler Sennacherib (704–681 BC) sacked the city, destroyed the temple of Annunita and abducted the statue of Shamash. However, one of the most devastating attacks of Sennacherib’s reign was against Babylon in 689 BC Not only did he order his soldiers to take or destroy all of the city’s statues of their gods, he also diverted the flow of the Euphrates River in order to completely destroy the city.

The Dragon Marduk. Many Babylonian deities have animal representations with Marduk often depicted as the “snake-dragon,” as seen in this glazed brick relief from King Nebuchadnezzar’s Ishtar Gate constructed in 575 BC Marduk was the patron god of the city of Babylon, where his ziggurat tower, Etemenanki, was built. This tower is often associated with the biblical “tower of Babel” and is mentioned in the Annals of the Assyrian king Sennacherib, who claims he destroyed the temple tower of his Babylonian enemies in 689 BC

The Dragon Marduk. Many Babylonian deities have animal representations with Marduk often depicted as the “snake-dragon,” as seen in this glazed brick relief from King Nebuchadnezzar’s Ishtar Gate constructed in 575 BC Marduk was the patron god of the city of Babylon, where his ziggurat tower, Etemenanki, was built. This tower is often associated with the biblical “tower of Babel” and is mentioned in the Annals of the Assyrian king Sennacherib, who claims he destroyed the temple tower of his Babylonian enemies in 689 BC

As an example of the reverence some rulers held for the city of Babylon, the Neo-Assyrian ruler Esarhaddon (r. 680–689 BC) bragged about returning the statue and treasures of Marduk to his temple in Babylon from Elam after conquering and plundering the ancient Iranian kingdom. His son, Ashurbanipal (668–627 BC), would later follow in his father’s footsteps, returning the statues of exiled gods to several Mesopotamian cities. Ashurbanipal had the same mind-set as his father in that both of them believed the military campaigns of their predecessor Sennacherib were too severe. In order to please the gods and earn their forgiveness, he returned abducted statues to Sippar and the statue of the goddess Nanna to Uruk. The Neo-Assyrian monarch had even claimed the goddess had spoken to him and said, “Ashurbanipal shall bring me out of wicked Elam.”

It was not long after the fall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire that the culture of Mesopotamia changed and the abduction of the gods of rivals ceased in the region. To avenge the atrocities committed by Sennacherib on Elam, the successors of the ancient Iranian kingdom known as the Medes allied with the Babylonians to invade Assyria.

In 612 BC, the Medes and Babylonians besieged the Assryian capital, Nineveh, for three months until the city fell. The combined forces successfully conquered the empire, but their ascendency in the region was short-lived as well. To the south of the Medes, the Persian king Cyrus II led numerous highly successful military campaigns and greatly expanded his territory. In 539 BC, he invaded Babylonia and the city lost its independence. The Persians would come to rule Mesopotamia for the next 200 years and thus the era of competing independent kingdoms, city-states and empires came to an end in the region.

The centuries that followed certainly were not entirely peaceful, but even as the Macedonians, Parthians, Sassanid Persians and various other people gained control of the region, Mesopotamia became nearly consistently under the rule of one monarch. With the new conquerors came their religions, including the beliefs of the Greco-Romans, Zoroastrianism and eventually Islam. The practice of abducting gods ended, just as the religion of ancient Mesopotamia faded away.