The recent archaeological discoveries at a tomb found at Amphipolis in Greece have renewed widespread interest in a long debate as to where Alexander the Great was buried.

On November 12, 2014, BBC News reported that “the excavation [at Amphipolis] has fascinated Greeks ever since Prime Minister Antonis Samaras visited the site in August 2014 (News from the World of Archaeology, Vol. 21:5) and announced it amounted to “an exceptionally important discovery.” The latest revelations have only added to Greek excitement about the identity of the person entombed at Amphipolis. Excitement indeed: for if this tomb proved to have any direct association with Alexander the Great, it could have ramifications for the resurgent nationalism in contemporary Greece.

However, unlikely the proposition may seem, the potential for the discovery of Alexander’s remains on Greek soil is inestimable. Even as recently as the 1990s, there was a push to maintain that Alexander’s remains, along with those of his wife, Roxanne, had been transferred at some point in ancient times to the official burial site at Aegae, the capital of the Macedonian kingdom and the location of Alexander’s father’s tomb. At the time of writing, no claims have been made that Alexander and Roxanne lay in the tomb at Amphipolis—at least not from any official source—but speculation is rife, not only because the structure discovered there is the most impressive tomb ever to be unearthed in Greece, but because its date is contemporaneous with Alexander’s rule. And what makes the possibility of a link to Alexander more tenable is the fact all knowledge of Alexander’s grave has been lost in time.

Questions over entombment

The reason why the current location of Alexander’s corpse remains a plausible speculation is because for a dead man, he has proved to be remarkably peripatetic—the whereabouts of his final resting place a mystery for over 1600 years. The term “final resting place” is used advisedly, for such were the conditions surrounding his death, it is not certain his remains now reside in a tomb at all. The mystery that shrouds one of the most significant figures in human history remains to this day.

What is known of Alexander’s fate following his death in 323 b.c., is that his body lay in state in Babylon for two years while a hearse was built to carry him on his long journey home to Aegae. However, this planned return to his homeland wasn’t without controversy. While it conformed to the wishes of Perdiccas, Alexander’s most senior general, it effectively countermanded Alexander’s own dying wish to be buried at the Oasis of Siwa in Egypt. It also ran counter to the ambitions of another of Alexander’s generals, Ptolemy. Ptolemy had accompanied his leader to Siwa in 331 b.c. and wished to see Alexander buried, at the very least, somewhere in Egypt. Yet, even here, self-interest was at the forefront of both plans. Ptolemy saw, as had Perdiccas, the political advantage Alexander’s final resting place would have for the one who prevailed in the struggle over the fate of his corpse. Macedonian custom dictated any new king assert his right to the throne by burying his predecessor, and so control over the fate of Alexander’s remains was vital to each man’s political ambitions.

There is quite a bit known about the final days of Alex- ander. On his deathbed, the young monarch removed his ring from his finger and gave it to Perdiccas, effectively nointing him regent and protector of Alexander’s wife, Roxanne, and their son, Alexander IV. This act should have sealed Perdiccas’s position of supremacy, but the matter didn’t end there. Alexander’s senior generals vied to fill the power vacuum that his death had left. And so while Alexander’s body lay in state in Babylon, politick- ing ensued. “Alexander’s corpse was a key to the future of the Hellenistic world he had brought into being. His reputation as the greatest conqueror in history made his body a magnet for soldiers who would flock to the banner of his successor. Alexander’s tomb would become the centre of a religious cult. He was a god in Asia, even if only a peerless king in Macedonia and Greece” (Saunders, Alexander’s Tomb: The Two Thousand Year Obsession to find the Lost Conqueror, pp 34, 35).

Alexander was perceived to be as politically important in death as he had been in life. And, as it turned out, as important to Ptolemy’s political ambitions in Egypt as they were to Perdiccas’s elsewhere.

Hijacked Corpse

Not even a quarter of the way into its journey to Macedonia, before reaching Damascus, Ptolemy’s forces ambushed the funerary cortege and hijacked the hearse and diverted it to Memphis in Egypt in 321–320 b.c. There, for the first time, Alexander was laid to rest in a tomb. However, soon after., Perdiccas led an attack on Ptolemy into Egypt—a mission which failed and led to Perdiccas’s own assassination. A short 15 years later, Ptolemy assumed the title granted to Alexander in his own lifetime: king-pharaoh of Egypt. Some time before his own death in 283 b.c., he transferred Alexander’s body to Alexandria, the capital of Egypt (and named by Alexander in his own honour), to be interred in another tomb. In 215 b.c., Alexander was again relocated to a tomb inside the Soma Funerary Park built by Ptolemy IV Antipater: it was to become a place of veneration where Alexander could be worshipped as a god. It also became Alexander’s last confirmed resting place.

Lost Forever

There are two main reasons why Alexander’s whereabouts have been lost. The first involved the suppression of pagan beliefs throughout the Roman Empire, subsequent to Emperor Constantine’s conversion to Christianity in A.D. 323. This included a crackdown on the pagan practice of venerating the tombs of their heroes. In Alexander’s case, the city’s Christian hierarchy saw his tomb increasingly as a competitor to the veneration of the tomb of Christ in Jerusalem. Around A.D. 360, civil unrest and rioting - stemming from religious differences between Christians and pagans shook the city. Around this time, Georgias, the bishop of Alexandria, publicly declared he would destroy “the Temple to the Genius,” interpreted by some to be a reference to the tomb of Alexander. Pagan outrage over Georgias’s declaration, however, saw him murdered before he could make good on his threat. Yet, Alexander’s tomb could have been damaged during these years of unrest.

The second and more significant disaster, occurred on July 21, A.D. 365, when a tsunami struck Alexandria and wrought untold destruction. The event is still remembered annually, 1700 years later, as “a day of horror.” Five thousand lives were lost in the city and untold more in the rural surroundings. Fifty thousand of the city’s dwellings were destroyed and the royal precinct inundated. Alexander’s tomb was almost certainly impacted. If it survived at all, its condition would have been parlous. Thirty-five years after the tsunami, Alexander’s tomb was last referenced by John Chrysostom, the archbishop of Constantinople, when on a visit to Alexandria, he stated, “his [Alexander’s] tomb even his own people know not.” From that time on, the record of Alexander’s mortal remains disappears from history.

Do Alexander’s remains still moulder in Alexandria unseen, beneath the ruin the city was rebuilt upon, or were they dispersed by the wall of water that bore down on the populace? Is it possible that subsequent to the natural disaster, Alexander’s body was spirited away to safety by his devotees and preserved in some unknown place? Or could Alexander have met an even more ignominious fate: his corpse looted and broken up to form sacred relics, to which even the Christians of Alexandria were partial? The uncertainty over the fate of Alexander’s remains means there will always be conjecture, and thus controversy, about his final resting place.

The Tomb at Amphipolis

The mystery over the location of Alexander’s remains allows for the finds at the tomb at Amphipolis to be the subject of excited speculation, not the least because, coupled with its fourth century b.c. construction as already stated, it is regarded by many to be the most impressive tomb ever to be discovered in Greece.

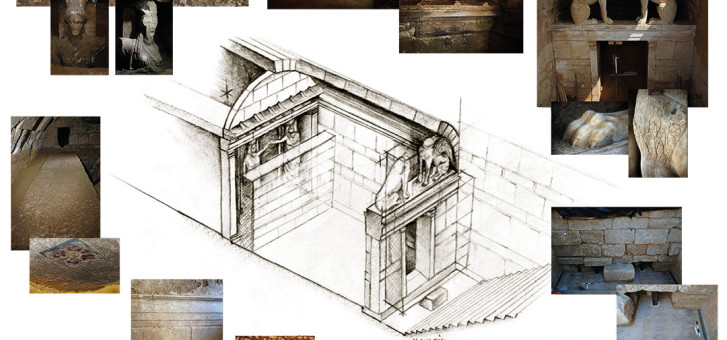

The archaeological investigation at Amphipolis began in earnest in 2012 under the directorship of highly regarded Greek archaeologist, Dr Katerina Peristeri, and continues today. The preliminary findings situate the tomb under an imposing 30-metre (100 ft) high tumulus—an artificial mound built over a tomb. However, rather controversially, the geologist on the site, Evangelos Kambouroglou, broke ranks with the rest of his colleagues and announced on March 7, 2015, he believed the tomb had been dug into a naturally-formed hill rather than one built by human hands. In any event, the mound is surrounded by a three- metre (10 feet) high limestone wall with a marble facing (transported from the island of Thassos) of impressive precision. The wall itself is topped with a finely-worked cornice. Preserved under layers of soil for untold centuries until its recent excavation means it is still in good condi- tion. This wall is roughly circular, surrounding the entire mound, a half-kilometre (0.3 mile) in circumference. It is, in itself, a measure of the tomb’s importance.

Stumbling upon the tomb in ancient times would have been a breath-taking experience. In her preliminary findings, Peristeri also discovered that until recent times, the crest of the mound was surmounted by a detailed stone lion standing 5.3 metres (17 ft) in height, set upon a plinth which raised it a further 10.5 metres (34 ft) over the landscape. While no longer at the site, this statue still exists, in pieces on the banks of the Strymonas River several kilometres away and subsequently reassembled nearby. Such lion statues were generally used to honour a victory at a battlefield or used to adorn the tomb of a great general. Since there are no recorded battles near this site around the time of its construction, and because it surmounts a grand tomb, the latter is thought the more likely explana- tion. Peristeri ventured as much in an interview with the BBC in November 2014.

Kambouroglou, on the other hand, believes the lion could not have surmounted the tomb as its sheer weight (approximately 1500 tonnes) would have caused the walls of the tomb directly below to collapse immediately upon installation. Clearly, much is yet to be learned from the site before a more definitive understanding of the significance of the tomb can be drawn.

Yet, if Peristeri’s deductions were correct and a great general or some royal personage had been interred there at some time in the past—and the tomb is grand enough to warrant this preliminary speculation with or without a stone lion surmounting the summit—then for whom could it have been intended? Alexander himself? The style and size of the tomb, as well as its age and provenance, tick many boxes. While it may be improbable, according to Peristeri, “Nothing is impossible, at the moment we are ruling nothing out.” To many, such a statement is tantamount to a blank cheque—for the time being at least.

The fact Alexander’s body remained in Egypt until at least the fourth century A.D. would seem to militate against the Amphipolis site as ever having been envisaged for Alexander’s use. Yet there remains the possibility that the Amphipolis tomb could have been intended for him—construction having commenced during his lifetime in preparation for his final journey over the River Styx—whenever that eventuated. If this were the case, it would explain both the timing of its construction as well as the nature of the structure. And because we know the main protagonists who strode the Macedonian stage at this juncture of history, we can safely state there is no one of near equal stature to that of Alexander within this time frame. This would suggest a strong link between the tomb at Amphipolis and Alexander in some form or other, at the very least.

The plan to return Alexander’s body to Aegae spoke more of Perdicca’s political ambitions than Alexander’s wishes. The ill-will which existed between Alexander and his father, Phillip, at the end of Phillip’s life could explain why Alexander had no desire to be buried at Aegae alongside his father. And the reason why Amphipolis didn’t become his final resting place could simply be because of his sudden death on territory far from home.

But why Amphipolis? Why would Alexander sanction the construction of his tomb at a site that appears to have had no particular importance to him? Granted, Alexander used its port as a naval base during his Asian campaign, but apart from three of his most important naval admirals being native sons of Amphipolis, it doesn’t appear to have been of any further significance. If the city did gain relevance to Alexander, it was only 14 years after his death, following the murder of his wife and his son within the city’s precincts.

Set against this is Alexander’s dying wish to be buried in the necropolis at the Oasis at Siwa. This may have stemmed from his realisation of the difficulty involved in return- ing his body from Babylon to his homeland. Subsequent to Alexander leaving Macedonia for good, rather than discounting the Amphipolis hypothesis completely, his decision to be buried at Siwa could mean he had simply changed his plans.

What is more likely however, is the impact of Alexander’s visit to the Oasis of Siwa in 331 b.c. The priests of the oracle there announced Alexander, rather than being the natural son of Phillip, was instead the divine son of the god, Zeus. Such a grandiose notion had appeal to Alexander. There is even evidence he had been primed from childhood to accept this mind-set. History tells us Olympias, his mother, was the most important influence in Alexander’s life. She was also a mystic and claimed she had been impregnate by Zeus, placing within Alexander’s young, impressionable mind the possibility he was the progeny of a divine being rather than of a human king. It is possible as Alexander embraced his role in Egypt, filial earthly connections were overridden by his growing self-belief that he was the divine offspring of Zeus, leading to his wish to be buried at Siwa. All previous plans would likely have paled into insignificance at this new enlightenment regarding his affirmed divinity.

But back to the tomb.

Inside the Amphipolis Tomb

Peristeri unearthed the entrance to the Amphipolis tomb in August 2014. Inside are clues to the regal nature of the construction’s provenance. The entrance is guarded by a pair of chimera—Greek-styled sphinxes combining features of human, bird and lion—set in the arch above the doorway. They have been vandalised—beheaded at some point in time—otherwise each would have stood around two metres (6.5 ft) tall. Inside, supporting the roof of the first section, are two columns in the form of finely detailed caryatids, human females with hair hanging to their shoulders, dressed in ankle-length belted garments and standing almost four metres (13 ft) tall on their pedestals. Their hands are extended to prevent entrance to the inner sanctuary of the second chamber. Beyond them, on the floor of the first chamber, is a large mosaic of approximately 13 square metres (140 sq ft) covering the entire surface. It is characteristically Macedonian in style, portraying the goddess Persephone, her red-gold locks flowing, dressed in a white tunic with a red ribbon tied at her waist. She is being abducted by Hades, his chariot drawn by two white horses being led into the underworld, in turn, by Hermes.

The third chamber contains the burial itself and it is where hundreds of bone fragments have been found. In addition, there are iron and copper nails from a wooden coffin, as well as pieces of glass and bone decoration remains after the coffin’s decomposition. The tomb has been looted, possibly in antiquity, and there is nothing which remotely approaches a complete skeleton. (There are also wall remains dating from the Roman period, suggesting that attempts were made during that time to protect the integrity of the tomb.) While Peristeri has not identified the corpse beyond the possibility that it was that “of a great general,” speculation has been rife.

The classical archaeologist, Dr Dorothy King, has suggested it could be the tomb of Hephaestion, a friend and possible lover of Alexander who predeceased him. She has also ventured that there is a resemblance between the figure of Hades in the second chamber floor mosaic and that of Phillip, Alexander’s father. Others have proposed all three figures in the mosaic had actual human counterparts: Phillip represented as Hades (Phillip’s damaged right eye conveniently hidden by virtue of being presented in profile), the young, clean-shaven Hermes a portrayal of Alexander and the red-headed Persephone his mother Olympias. The tomb, by this reckoning, was intended for Queen Olympias, the Persephone being escorted into the afterlife.

Andrew Chugg, another knowledgeable commentator onthe Amphipolis excavation, has observed that sphinxes are rarely found in Macedonian tombs of Alexander’s time, but were found in the tombs of two Macedonian queens, one being Alexander’s grandmother. Chugg goes on to suggest that this could point to Amphipolis being home to the tomb of another Macedonian woman of great status, either Roxanne, Alexander’s wife, who was put to death there, or Olympias, his beloved mother.

By the end of January 2015, it was confirmed that the majority of the bones—the skull cap and jaw, parts of both arms and both legs, both sides of the pelvis and some other smaller fragments—belonged to a female in her sixties. However, there are also those of a male in his mid-forties, as well as another male in his mid-thirties who, by virtue of cut marks on the left upper-thoracic spine, vertebra and other bones, appears to have been hacked to death. There are also small skull and arm bones from an infant and nine partial bones from a cremated adult. There are also animal bones, possibly of a horse. This could suggest it was a family tomb, complete with burials subsequent to the original internment. But the bones could also represent totally independent burials, compiled over centuries, meeting no criteria other than the tomb being a convenient site for later burials. However two facts are highly significant: Peristeri has stated the inhabitants of the area have known the mound as “the tomb of the queen” and Olympias was close to 60 years of age at the time of her murder, approximately the age of the female skeleton found inside the tomb.

There remains much work to be done on the Amphipolis tomb, as evidenced by the conflicting statements of Peri- steri and Kambouroglou. There is more discovery, sifting, analysis, theory formation to be done. Consequently it may still be some time before the considered verdicts are in. It is unlikely that news of the Amphipolis tomb is likely to go away any time soon, but whatever it is, it likely to be exciting and enlightening.