In 1986. Professor Gabriel Barkay was introducing a ground-breaking new discovery made at Ketef Hinnom, a burial site southwest of Jerusalem, where the oldest ever biblical inscription to date had been found. I sat spellbound with hundreds of Old Testament scholars at a meeting of the International Organization for the Study of Old Testament in Jerusalem’s Israel Museum.

Two tiny strips of silver, tightly wound and appearing like miniature scrolls had been carefully unrolled. They contained etched inscriptions bearing a shortened ver- sion of the Aaronic blessing of Numbers 6:24–26. Based on the archaeological context and style of script, Barkay dated the inscription to the late seventh or early sixth centuries BC—400 years older than the Dead Sea Scrolls. The silence was palpable in the room as many critical scholars (who dated this text in Numbers to the fourth century BC) were suddenly confronted with new evidence. Recent photographic techniques and new computer imaging conclusively dated the amulets to before the fall of Jerusalem to the Babylonians in 586 BC This means they date at least 150 years earlier than critical scholarship has assumed for the origin of Numbers, making the Ketef Hinnom inscription the earliest written biblical passage discovered to date. This was my dramatic introduction to archaeology’s power to challenge current interpretations of the Bible.

Since the dawn of archaeological research in the ancient Near East in 1799, no other discipline has provided more new data and insights on the nations, people and events of the Bible. Discoveries in the nineteenth century have been multiplied many times during the past 150 years of archaeology in the land of the Bible as artefacts, cities and ancient records reveal the trustworthiness of the Bible.

Following is a review of some of the most important finds made during the past 25 years by archaeologists working in the Middle East who have contributed greatly to the understanding of the Bible.

1. Nations of the Bible

Cannan

The land of Canaan has been greatly illuminated in recent years through ancient texts and also through excavations at major sites like Hazor, the largest Canaanite city in Israel (see Joshua 11:10; Judges 4:2). Not only have modern excavations revealed a fortified site of some 200 hectares (500 acres), but textual sources indicate it was the south-westernmost city in an international trade system extending from Iran to the Mediterranean that included other centres like Babylon, Mari and Qatna. The site is mentioned in omens and geographical lists from Babylon and in the Mari texts. At the time of writing, 16 cuneiform documents have been found at the site so far, ranging from administrative letters to court records. The most recent discovery of a law code fragment was made in 2010 on the surface of the site. These records attest to the central and significant role Hazor played in the geopolitical climate of Bronze Age Canaan.

Philistia

The Philistine cities of Ashkelon, Ashdod, Ekron and Gath have been excavated extensively, revealing a sophisticated culture of architecture, art and technology. In 1996, an in- scription was uncovered at Ekron in southern Israel, which mentions a dynastic line of five kings—including Achish, the son of Padi—that ruled Ekron until the destruction of the city by Nebuchadnezzar. The decorated Aegean-style pottery, the elaborate architecture and the technology of these cities reveal the Philistines were the elite in the ancient land of Canaan.

Judah

Even in an age of scepticism toward some of the Bible’s most famous kings, including David and Solomon, new discoveries call for caution among those who claim the Bible’s record of the kingdom of Judah is mythical. New excavations since 2007 at Khirbet Qeiyafa, by the Hebrew University and Southern Adventist University, have revealed a massively fortified garrison city dating to the time of the Hebrew kings Saul and David. Surrounded by 200,000 tonnes of double-fortified (or casemate) walls, with evidence of city planning, this garrison town was situated on the Elah Valley, overlooking the area where the famous battle between David and Goliath was fought (1 Samuel 17). The city is a precursor to later Judean cities with similar design elements. In 2009, a second gate was uncovered, which now identifies Khirbet Qeiyafa with the biblical city of Shaaraim, mentioned in 1 Samuel 17:52. This has major implications for the early history of Judah and the establishment of the United Monarchy.

2. Peoples of the Bible

The existence of at least 70 biblical characters, including kings, serv- ants, scribes and courtiers has been confirmed over the past two centuries of research. In the past two decades, many more people were added to this list through the discovery of seals, seal impressions, ostraca and monumental inscriptions.

Baalis

At the site of Tall al-Umeiri in Jordan, archaeologists in 1984 uncovered a clay seal impression bearing the name “Milkom’ur . . . servant of Baal- yasha,” undoubtedly a reference to Baalis, the king of ancient Ammon, mentioned in Jeremiah 40:14. This obscure king was said to have plotted against the Judean king at the verge of the Babylonian destruction.

David

The excavations in 1993 at the northernmost biblical city of Tel Dan uncovered an inscription. The campaign account by an Aramean king mentioned for the first timethe “house of Israel” and the “house of David,” clearly a reference to the southern kingdom of Judah and to Israel’s most famous king. David not only existed, but he was remembered over a century later as the founder of a great dynasty.

Herod

Archaeologists have excavated Herod the Great’s luxurious palaces at Cae- sarea Maritima, Herodium, Masada, Jericho and other sites. Herod spared no expense to decorate these buildings with detailed mosaics, frescoes and architectural elegance. At Masada, Herod’s desert fortress, the northern three-tiered palace had a nearly 360- degree view overlooking the Dead Sea. In 1996, I excavated with Ehud Netzer at Masada, where we uncovered an imported fragment of a wine amphora. On the fragment was an inscription: regi Herodi Iudaico—“for Herod, king of Judaea.” It was the first mention of Herod the Great’s title outside the Bible’s New Testament and the writings of Josephus, found in an archaeological context.

Nebo-Sarsekim

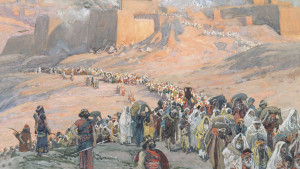

In 2007, a researcher in the British Museum deciphered an inscription of a financial record mentioning a donation made by a Babylonian official named Nebo-Sarsekim. The inscription dates to the tenth year of the reign of the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar, about 595 BC (2 Kings 24:1–4; Daniel 1:1; 2:1). This official, Nebo-Sarsekim, is also mentioned in Jeremiah 39:3, where he appears in the account of Nebuchadnezzar’s second campaign against Jerusalem in 597 BC In the biblical account, over 10,000 captives are taken to Babylon, but Nebuchadnezzar tasks Nebo-Sarsekim with taking care of the prophet Jeremiah, who is left behind in Jerusalem. This mention of the same person in a financial record of Babylon indicates the impor- tance of continued research in translating the thousands of discovered texts in the basements of museums that have never been deciphered or published.

3. Writing the events of the Bible

The Dead Sea Scrolls, found by a Bedouin shep- herd in 1947, were one of the most amazing discoveries to testify to the accuracy of the Bible’s transmission over 1000 years of history. In more recent years, questions about the extent of literacy in ancient Israel have been raised. Some scholars even question whether Hebrew writing extended back to the tenth century BC, while others go so far as to claim Hebrew was an invention of the Hellenistic period 700 years later. In recent years, several discoveries have been made that challenge this hypothesis.

A Tenth-Century Abecedary

In 2005, an ancient stone inscription was found at the site of Tel Zayit, excavated by the Pittsburgh Theological Seminary. On it, an abecedary, or alphabet with 18 letters, was dated by the ceramic and archaeological evidence to the tenth century BC—the time of King Solomon or shortly thereafter. The building in which it was found was destroyed in a massive fire, leaving debris nearly one metre thick over the area. Excavators have dated this destruction to Shishak (1 Kings 14:25–28) but possibly someone else, in 925 BC The Tel Zayit abecedary is one of the oldest attestations of the alphabet known. Since it was found in a clear archaeological context that dates it to the tenth century b.c, the abecedary also provides a distinct connection between the development of language in ancient Israel and the growing archaeological evidence of cities and buildings during the United Monarchy.

Oldest Hebrew Inscription

During the second season excavations in 2008 at Khirbet Qeiyafa, the site in the Elah Valley mentioned earlier, a text was found written on a broken piece of pottery. The ostracon consisted of five separated lines and begins with the injunction, “Do not do . . .” The initial phrase is only found in Hebrew and has led Haggai Misgav, the epigrapher, to suggest the inscription is Hebrew. If this is true, it would be the oldest Hebrew text ever found to date—some 800 years older than the Dead Sea Scrolls. Unfortunately, much of the rest of the text is incomplete with missing and obscure letters. One suggestion, although highly speculative, is this text is an injunction for the protection of widows and orphans. Gary A Rendsburg of Cornell University has observed, “Taken together, the Tel Zayit abecedary, the Khirbet Qeiyafa inscription and the Gezer calendar demonstrate writing was well-established in tenth-century Israel—certainly sufficiently so for many of the works later incorporated into the Hebrew Bible to have been composed at this time.” An even more recent discovery was made in Jerusalem by Eilat Mazar in 2012. The Ophel inscription is incised on a storage jar and found in what appears to be an eleventh or tenth century context. The existence of writing at such an early stage of the Iron Age is significant, because it implies historical data could have been documented and passed on from the early tenth century BC until the biblical narrative was finally formulated. It also suggests the paucity of evidence for writing is less secure than previously thought.

In Conclusion

Archaeology remains one of the most significant disciplines providing new information for the world of the Bible. While it may be tempting for some to ask, for example, “What about this person of the Bible?” or “Why do we not have evidence for this event yet?” we need to be reminded that although over 200 years have passed since the discipline was established in the ancient Near East, we have barely scratched the surface—literally and figuratively. Only a fraction of biblical sites are known, and of those that are, only a fraction have been excavated. Then, most of those excavated have only had perhaps five per cent of the site uncovered; with fewer yet fully published. Of those that have been published, not everything has a direct bearing on the Bible. For these reasons, one needs to be cautious in making negative assessments of events and history.

One thing is certain, with the continued support for archaeological research in this part of the world, the next 20 years will no doubt reveal further illuminating discoveries, which in some dramatic cases, will directly impact our understanding of the Bible record.

By the numbers

16 cuneiform documents discovered so far at the site of Hazor, attesting to the central and significant role the town played in the Bronze Age of Canaan.

5 Kings listed in an inscirption incoverd at Ekron revealing the Philistines were the elite in the ancient land of Canaan.

70 Biblical characters, including kings, servants, scribes and courtiers have been confirmed over the past two centuries of reseach.

18 letters of the Hebrew ancient alphabet discovered in Tel Zayit in 2005 prove the development of language in Israel in the tenth century BC

Over 825 Dead Sea Scrolls ave been identified by scholars; they are the oldest group of Old Testament manuscripts ever found testifying to the accuracy of the Bible over 1000 years of history.

Sources

- G Barkay, A G Vaughn, M J Lundberg and B. Zuckerman, “The amulets from Ketef Hinnom: A new edition and evaluation,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, no 334 (2004), pp 41–71; Barkay, et al, “The challenges of Ketef Hinnom: Using advanced technologies to uncover the earliest biblical texts and their context,” Near Eastern Archaeology, vol 66, no 4 (2003), pp 162–171.

- For a general overview, see A Hoerth, Archaeology and the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1998); J McRay, Archaeology and the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2002); C E Fant and M G Reddish, Lost Treasures of the Bible (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2008).

- For an overview of the major Egyptian textual evidence for Canaan, see M G Hasel, “Pa-Canaan in the Egyptian New Kingdom: Canaan or Gaza?” Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections, vol 1, no 1 (2009), pp 7–15; on the cuneiform evidence, see A F Rainey, “Who is a Canaanite? A review of the textual evidence,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, no 304 (1996), pp 1–15; Rainey, “Amarna and later: Aspects of social history,” in W G Dever and S Gitin, eds, Symbiosis, Symbolism and the Power of the Past: Canaan, Ancient Israel, and Their Neighbors from the Late Bronze Age Through Roman Palaestina (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2003), pp 169–187.

- W Horowitz, “Two late Bronze Age tablets from Hazor,” Israel Exploration Journal, vol 50, no 1/2 (2000), pp 16–28.

- W Horowitz and T Oshima, Cuneiform in Canaan: Cuneiform sources from the Land of Israel in Ancient Times (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society/Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2006), pp 65–87.

- For further references, see T Dothan, The Philistines and Their Material Culture (New Haven: Yale University, 1982); Dothan and M Dothan, People of the sea: The search for the Philistines (New York: Macmillan, 1992); S Gitin, “Philistines in the books of Kings,” in A Lemaire, B Halpern and M J Adam, eds, The Books of Kings: Sources, Composition, Historiography and Reception (Leiden: Brill, 2010), pp 308–309.

- S Gitin, T Dothan and J Naveh, “A royal dedicatory inscription from Ekron,” Israel Exploration Journal, vol 47, no 1/2 (1997), pp 9–16.

- I Finkelstein and N A Silberman, David and Solomon: In Search of the Bible’s Sacred Kings and the Roots of the Western Tradition (New York: Free Press, 2006); J Van Seters, The Biblical Saga of King David (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2009).

- On the dating of the site, see, Y Garfinkel, K Streit, S Ganor and M G Hasel, “State formation in Judah: Biblical tradition, modern historical theories and radiometric dates at Khirbet Qeiyafa” in Radiocarbon: Proceedings of the 6th International Radiocarbon and Archaeology Symposium, vol 54, no 3–4 (2012), pp 359– 369; for general overview, see Y Garfinkel, S Ganor and M G Hasel, “Khirbet Qeiyafa,” in D M Master, ed, The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology and the Bible, vol 2, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), pp 55–62.

- Garfinkel, Ganor and Hasel, “The contribution of Khirbet Qeiyafa to our understanding of the Iron Age period,” in Strata: Bulletin of the Anglo-Israel Archaeological Society, vol 28 (2010), pp 39–54; Garfinkel, Ganor and Hasel, “The Iron Age city of Khirbet Qeiyafa after four seasons of excavation,” in G Galil, ed, The Ancient Near East in the 12th–10th Centuries BCE: Culture and History (Münster: Ugarit Verlag, 2012), pp 149–174.

- On the most recent site report, see Garfinkel, Ganor and Hasel, Khirbet Qeiyafa Vol 2 Excavation Report 2009- 2013: Stratigraphy and Architecture (Areas B, C, D, E) (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 2014).

- R W Younker, “Israel, Judah, and Ammon and the motifs on the Baalis seal from Tell el-‘Umeiri,” Biblical Archaeologist, vol 48 (1985), pp 173–180.

- A Biran and J Naveh, “An Aramaic stele fragment from Tel Dan,” Israel Exploration Journal, vol 43, no 2/3 (1993), pp 81–98; C E Fant and M G Reddish, Lost treasures of the Bible (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2008), pp 103–106.

- On his building program, see E Netzer, “Herod’s building program,” in D N Freedman, ed, Anchor Bible Dictionary, vol 3 (New York: Doubleday, 1992), p 169; Freedman, The Architecture of Herod the Great Builder (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2008).

- “Pottery with a Pedigree: Herod Inscription Surfaces at Masada,” Biblical Archaeology Review, vol 22 no 6 (Nov–Dec, 1996), p 27.

- The official translation from M Jursa is forthcoming, see provisionally B Becking, “The identity of Nabu-sharrussu-ukin, the chamberlain. An epigraphic note on Jeremiah 39,3. Appendix on the Nebu’sarsekim tablet,” in Biblische Notizen, vol 140 (2009), pp 35–46.

- See I Finkelstein and N A Silberman, David and Solomon: In search of the Bible’s Sacred Kings and the Roots of the Western Tradition (New York: Free Press, 2006), p 142; P R Davies, In Search of “Ancient Israel,” (Sheffield: JSOT Press, 1992).

- R E Tappy, P K McCarter, M J Lundberg and B Zuckerman, “An abecedary of the tenth century BCE. from the Judaean Shephelah,” in Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, no 344 (2006), pp 5–46; Tappy and McCarter, Literate Culture and Tenth-century Canaan: The Tel Zayit Abecedary in Context (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2008).

- H Misgav, Y Garfinkel and S Ganor, “The Khirbet Qeiyafa Ostracon,” in D Amit, G D Stiebel and O Peleg-Barkat, eds, New Studies in the Archaeology of Jerusalem and its Region (Israel Antiquities Authority and the Institute of Archaeology, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (Hebrew), 2009), pp 111–123; Misgav, Garfinkel and Ganor, “The Ostracon,” in Garfinkel and Ganor, eds, Khirbet Qeiyafa Vol. 1. Excavation Report 2007–2008 (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 2009), pp 243–257.

- G Galil, “The Hebrew inscription from Khirbet Qeiyafa/Neta‘im: Script, language, literature and history,” Ugarit Forschungen, no 41 (2009), pp 193–242.

- G. A Rendsburg, “Review of Ron E Tappy and P Kyle McCarter (eds), Literate Culture and Tenth-Century Canaan,” in BASOR, no 359 (2010), p 89.