As the hunter stood still in the shade of a huge boulder, he closely observed the bovid, which he hoped to overcome to provide food for his family and community. He hesitated as he held the spear, closely scrutinising the animal with its thick, bent horns, its ears alert, twitching often. He wasn’t sure if the animal had heard him, so he hesitated. The animal was powerful, and he stood in awe of it. With its strong jawline, solid muscular chest and hump, sturdy legs and hoofs that could trample a man, it was going to be quite a challenge to encounter this beast in action.

Later that night, after recalling the day’s successful hunt, his meal consumed, the hunter reflected more about the animal. Wanting to record what he had observed led him back to the same boulder where he took the time to carve the image of the animal, giving great attention to detail as he chiselled and chipped the surface.

It might well be that his petroglyph was among the first that a hunter or member of that community ever etched. But we’ll never know. The earliest petroglyphs in Egypt depict a now extinct wild cow called aurochs (Bos primigenius) and are found at the site of Qurta, about 640 km (400 miles) south of Cairo. The horns of these animals have been discovered in other later settlements nearby, proving that they did in fact exist and were not simply a stylized drawing, the whimsy of an earlier artist. As time progressed, illustrations of animals such as ibex, flamingo, ostrich, fish, snakes, scorpions, wild bovid and even hunters with spears were also painted onto ceramics recording life as it existed along the Nile so many millennia ago.

But was there a purpose for representing such images? Was it in an attempt to preserve their visual existence? It may have been simply to signify good hunting territory by indicating the variety of animals located in the region. The depictions may also have been created out of a sense of awe, spirituality or in gratitude for a successful hunt; after all, animals were the primary source of food and means of survival. Animals had many valuable uses: their pelts providing warmth and protection from the elements, their bones and horns could be fashioned into tools and were ornately carved into adornments such as combs for personal care, craftwork and even inventory tags.

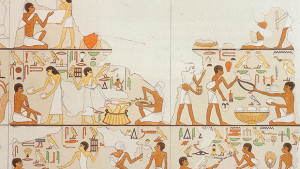

As an invaluable asset to a community, cattle could be used as draught animals, with their meat and milk also being vital. In addition, poultry, donkeys, sheep, pigs and goats were also farmed. Oxen are depicted on tombs and temple walls, ploughing the land for their owner in the afterlife and their meat was valued as temple offerings. Indeed, on many tomb walls, the food offerings for the afterlife depict a haunch of beef, geese and ducks, and actual mummified haunches of beef have been preserved from ancient Egypt. Their function was to serve as an eternal food source for the deceased.

For their playful antics and ability to be domesticated, many animals such as cats, dogs, monkeys, baboons, birds and geese became domestic pets. The ancient Egyptians adored cats, so much so that when a pet cat died the owner would shave off their eyebrows as a sign of mourning! And similarly for dogs, with their natural guarding ability, as Herodotus noted:

The occupants of a house where a cat has died a natural death shave their eyebrows and no more; where a dog has died, the head and the whole body are shaven. (Histories II, 66)

The tale of a dog known as Abuwtiyuw is quite extraordinary. Although no picture or body remains, this particular dog is identified from an inscribed stone tablet discovered in 1936. Abuwtiyuw was so special that he had gifts be- stowed upon him from the pharaoh! The tablet dates to the Sixth Dynasty of the Old Kingdom (c. 2345–2181 b.c.) and was found within the spoil heap of a mastaba near the Great Pyramid of Khufu, Giza. It is not known which pharaoh the dog served, but he was held in such esteem it is likely that Abuwtiyuw was mummified, as the ancient text (translated by Reisner, 1936) relates:

The dog, which was the guard of His Majesty, Abu- wtiyuw is his name. His Majesty ordered that he be buried [ceremonially], that he be given a coffin from the royal treasury, fine linen in great quantity, [and] incense. His Majesty [also] gave perfumed ointment, and [ordered] that a tomb be built for him by the gangs of masons. His Majesty did this for him in order that he [the dog] might be Honoured [before the great god, Anubis].

The inscribed text typifies Abuwtiyuw’s breed to be comparable to a greyhound or sight hound, with its curly tail and erect ears. Ancient Egyptians identified the breed as Tesem and a drawing of this dog appears very early in the Egyptian archaeological record, back in the Predynastic period of Egypt in Naqada.

The Egyptian museum in Cairo houses an incredibly well preserved, mummified saluki dog, with the hairs of the pelt of the magnificent animal still visible! Many other mummified animals are on display, including cats, monkeys, ibis, crocodiles, shrews and gazelles among others. Some animals were wrapped in intricately folded linen painted with obvious features leaving no doubt as to what is preserved underneath. However, occasionally X-rays of animal mummies have discovered secrets, with these “animals” being merely bundles of rags and a few bones!

The concept of sacred animals, the repository for the ba (soul) of the god in its familiar appearance, led to the formation of cults built on this premise. It is possible that such animal cults began in the Predynastic era, and more specifically, cattle cults. The deliberate placement of bull and sheep bones in one grave, and a fully articulated bull in another, each covered with layers of wood, clay and finally sandstone rubble, have been found in Nabta Playa, 100 km (60 miles) west of Abu Simbel and said to date to c. 4200 b.c. The presence of the bones of domesticated, long-horned cattle, and given the care and deliberation was afforded their burials, demonstrates their significance to the people of the early Egypt.

Many of the gods of ancient Egypt took the guise of animals and birds, whereby the animal was both the representation and also the repository of the god. Their appearance might be personified, with an animal head on a human body, or as the complete animal itself. The gods that were half-animal and half-human such as the jackal-headed god Anubis (who presided over embalming and the dead) are known as theriomorphic or hybrid, while the gods that appeared as animals, like Hathor in her cow form, are known as zoomorphic. It isn’t difficult to see the transition from pet to sacred animal; don’t cats rule our homes even today? But seriously, for the ancient Egyptians, their gods with animal manifestations were just as important and ingrained in their culture and religion as the gods that were represented as the anthromorphic; the all human.

All gods had to be appeased in order to benefit from their protection, blessings, assistance, fertility, love, guidance in the afterlife and in understanding creation itself. In one version of the creation, it was the ram-headed god Khnum sitting at his potter’s wheel who formed humans—something akin to the biblical creation story of the formation of Adam—from clay; he was also linked with the Nile, controlling the inundation. Such was his importance, that he was still being “consulted” in Ptolemaic times (c. 305–30 b.c.). This is evidenced by prayers inscribed on a rock called the Famine Stela, located near Aswan on the island of Sehel. Here the prayers acknowledge him as ending the famine that was triggered by low Nile floods.

Gods in their animal appearance could be represented in a human form as well, the images were not static and changed as the situation necessitated. Hathor, the goddess of love, happiness, joy, music, turquoise, motherhood, women, mother or wife of the king, foreign lands and their produce, also took on different guises; she even identified as the Mistress of the West, as required. There is a gloriously painted and detailed scene in the tomb of Nefertari where Hathor greets the queen in her anthromorphic appearance. It is only by the bovine horns securing a sun disk above Hathor’s head that we can identify her as a goddess.

But not all was beauty and sublime with divinities in animal representa- tions. There could be dual sides to their personality, one as protector and healer, and yet when angry they could be treacherous and destructive. Taking the icon of a lioness-headed woman, Sekhmet was a protector of the king in a motherly fashion. How- ever, when angered, as in the myth of The Destruction of Mankind, she almost slaughters all of humankind.

The impact of animals upon the lives of the ancient Egyptians went beyond that of food, pets and divine icons. It also delved into the area of architecture and furniture embellishments. Consider the feet of many stools, tables and chairs of this time, you will see lions paws with claws unsheathed, or the legs of bulls and hoofs. These are symbols of power, strength and majesty. On the golden throne of Tutankhamen, itself a symbol of authority, a leonine form has been used that features lion-shaped legs and apotropaic lion heads guarding from the front. On the so-called Painted Box of Tutankhamen, the pharaoh is depicted on both ends with a sphinx body, confidently trampling his enemies underfoot. The divine power of the animal gods continued in the symbolism employed in the furniture in Tutankha- men’s tomb with three ritual couches taking the form of Ammut “the devourer,” another as a lion or leopard and also as the cow-goddess Hathor. Many animals depicted with the vulture wings of protection wrapped around the shoulders of a pharaoh—a common theme—were employed across Egypt. The nemes striped crown of Tutankhamen features a cobra and vulture on his brow, ready to strike.

Another aspect of animals extended into Egyptian medicine and magic. There was an esoteric belief in the effect that specific qualities of animals could transfer to a human, in what is known as “sympathetic magic.” One account of such is recorded in the Ebers Medical Papyrus (c. 1550 b.c.), where animal produce was used for remedies, assisting with such things as covering grey hair in a wash or making hair thicker and stronger. The process involved to cover grey hair was facilitated by using the colour of the produce or animal part such as black ox or black calf blood boiled in oil; and to avert the onset of greying, the black horn of a gazelle was ground into a balm mixed with oil and applied.

Numerous gods with animal guises were worshipped in ancient Egypt. Whether they were adored at pets and faithful companions or worshipped in temples as gods, animals both wild and domestic have always been a significant part of the lives of ancient Egyptians, whether living or dead, as indeed, they still are today the world over.