The behistan (also known as Behishtun, Behistan or Bisotun) Inscription carved into a rock face in western Iran is one of the most remarkable monuments of the ancient Middle East. Fifteen-metres- (50 ft) high by 25-metres- (82 ft) wide, it is situated 100 metres (330 ft) up a limestone cliff near an ancient road that once connected two major cities of the sixth and seventh centuries b.c.: Babylon (the capital of Neo-Babylonia) and Ecbatana (the capital of its ally, Media). The monument stands on a branch of the great Aryan trade route, the Silk Road, later renamed the Royal Road of Darius the Great. Opposite, a caravanserai still provides rest for travellers.

In his third volume of The Seven Great Monarchies, historian George Rawlinson reported that, “the unusual combination of a copious fountain, a rich plain and a rock suitable for sculptures, must have attracted the attention of the great monarchs who marched armies through the Zagros range, as a place where they might conveniently set up memorials of their exploits.” His analysis is supported by the 16 other monuments also occupying the 116-hectare World Heritage site near today’s city of Kermanshah.

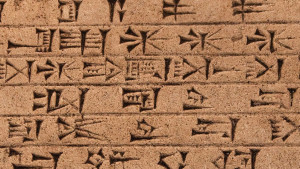

Three texts telling the same story in three different languages comprise this largest cuneiform document in the world—Babylonian (or old Akkadian); Elamite, the language of the administration of the Achaemenid Empire; and Aryan, now called Old Persian by western scholars to avoid the original Aryan nomenclature. Its discovery by Europeans in 1598 led to the translation of the ancient script on the monument, which has sometimes been referred to as the “Rosetta Stone” of cuneiform writing. Sculptures in the limestone cliff depict the supremacy of Darius the Great of Persia, whose ancestry, exploits and place in history are described. The placement of the writing around the pictorial material has created a spectacular objet d’art of great beauty within the minimalistic confines of the ancient Median and Persian traditions. Further, Darius’ claim that parchment copies of his account were made was verified by the discovery of some in Aramaic on the island of Elephantine in the Nile River near the city of Aswan in Egypt.

The eastern approach to Behishtan features twin, rugged peaks towering above the flat landscape. At the base of the mountain, the visitor looks up to a pronounced scar on the steep slope, emblematic of the inroads Darius made on history in his era. Part way up the mountain, a statue of the Greek god Heracles, whose presence was noted by the Greek physician Ctesias of Cnidus as an Assyrian sacred site, sits in sublime contemplation. Depicted satiating his thirst from a large cup, Heracles’ statue is considered the youngest Seleucid artistic piece in Iran. It commemorates the victories of the Seleucid Greek, Nicator Demetrius II, over Mithridates I of Parthia. Some writers have argued that the figure displays a synthesis between an ancient Iranian legend and the Greek religion that supplanted it.

Other reliefs include the larger than life Parthian reliefs of King Volgash hewn sometime between 50 and 200 b.c., located near an altar on the Balash stone at the base of the mountain, which hints at the carving’s religious importance. Mystery surrounds a Sassanid inscription mentioning the Romeo and Juliet-style love affair of King Khosrow and his wife Shirin. A relief of Mithridates I was partially obliterated by an arched niche ordered by the Savafid Sheikh Ali Khan Zangenahat, a governor of the province of Kermanshah, in the seventeenth century a.d. Another relief shows Gotarzes, the other Parthian king illustrated, to be deposing Mithridates II and his hated Roman connection. However, the vanquished king is afforded the protection of (or attempted assassination by) an angel, which is looping a thick rope over his head. Fortunately, the 1673 sketch of Mithridates II by the French traveller, Guilliaume-Joseph Grelot, was made before it was vandalised in 1673, and showed him with four individuals before him.

Others include Darius’ precise dates and time frames for his military actions. Sadly, damage to the monument by soldiers using it for target practice in World War II, and the irreparable destruction of the head of the Medes’ and Persians’ depiction of their deity, has signified the progressive loss of their ancient religion and many of its most spiritually empowering and socially stabilising tenets.

Over the centuries, visitors to the site speculated on the identity of the figures on the cliff face. An Arab believed he saw a teacher beating his pupils and a Christian thought he recognised Jesus and some of His disciples. Drawing the scene in 1818, the British scholar Ker Porter concluded it represented the conquering of the 10 tribes of Israel by the Assyrian King Shalmaneser.

The ascent to the inscription of Darius the Great is perilous. Originally, climbers made their way up a rock “chimney,” at the top of which they followed a narrow ledge on the rock face to the right to reach the ledge below the inscription. The most perilous section of the ascent is about halfway, where a step over a gap in the slight ledge is required. This ledge was later removed to prevent intruder access. Today, visitors ascend past cracked boulder-like shapes weathered into iron and copper shades to eventually stand in front of the great writings on another narrow ledge.

In the sculpture, the bow-wielding Darius the Greatv holds political sway over all other figures. The five-by- three-metre bas-relief shows his foot on his opposition, Gaumata, and reflects his subjection of the other nine figures, whose hands are tied and necks roped. Two servants, Intaphrenes, his bow carrier, and Gobyrus, his lance bearer, attend Darius, and a symbolic faravahar, a winged angel-like figure over his head, indicates the spiritually based hierarchical nature of the Mede and Persian governments. Two pieces of the composition, one of the figures and Darius’ beard, are thought to be later additions, as earlier copies of the original can be found further along the road.

Early translations emphasize Darius’ self-righteous claim that several imposters posing as legitimate candidates for the throne threatened his kingship and were duly eliminated. But the sculpture tells the real story—Darius eliminated all the rightful heirs to the Median Empire, one by one, as follows in the translation from the ancient Aryan language:

- Gaumâta, the figure under his foot, was the last Sha- hanshah (king of kings) of the Median Empire; he was Bardiya (Smerdis) son of Cyrus the Great, but it seems likely that Darius the Great and his co-conspirators called him Gaumata to hide their crime;

- First standing in line is Âçina king of Ûvja (Elam);

- Second is Naditabaira king of Bâbirush (Babylon);

- Third is Martiya king of Pârsa (Persia);

- Fourth is Fravartish king of Mâda (Media), grandson of King of Kings Cyaxares the Great;

- Fifth is Ciçataxma king of Parthava (Parthian), grand- son of king of kings Cyaxares the Great;

- Sixth is Frâda king of Mârgava (Margian);

- Seventh is Vahyazdâta king of Pârsa (Persia);

- The last is King Skuxa of Sakâ (Scythian) – “xaudâm: tigrâm : baratiy,” meaning, “He is wearing a pointed hat.”

At his inheritance, Darius, son of Hystaspes, received 23 countries from the Median Empire to rule. These countries are listed in the first column of the Behishtan cuneiform, with the direct translation in the Old Persian language as follows:

â : Auramazdâha : adamshâm : xshâyathiya : âham : Pârsa : Ûvja : Bâbirush : A

thurâ : Arabâya : Mudrâya : tyaiy : drayahyâ : Sparda : Yauna : Mâda : Armina : Kat

patuka : Parthava : Zraka : Haraiva : Uvârazmîy : Bâxtrish : Suguda : Gadâra : Sa

ka : Thatagush : Harauvatish : Maka : fraharavam :

dahyâva : XXIII : thâtiy : Dârayavaush

Translated into English, this reads:

Auramazdâ (God), he is mankind king, he is the king and law givers, for these countries, Persian, Elamite, Babylonian, Assyrian, Arabian, Egyptian, [those] who are beside the sea, Sardisian, Ionian, Median, Arme- nian, Cappadocian, Parthian, Drangianan, Arian, Chorasmian, Bactrian, Sogdianan, Gandaran, Scythian, Sattagydian, Arachosian and Makan: the most known countries are 23 kingdoms. Praise upon Darius.

Although Darius the Great claimed Persian heritage in his memoir, he was also Median and perhaps even Jewish. According to the Greek historian Herodotus, his father Darius Hystapses was a Persian satrap from eastern Iran and his mother was Rhodugune, thought to be the daughter of the Jewish captive girl, Hadassah, who became Queen Esther, third wife of Ahasuerus the Mede. Ahasuerus was also father of Darius the Mede (see Daniel 9:1), born in 601 b.c. (Daniel 5:31), most likely to his first wife Queen Vashti

see Esther 1:9), another little known figure. These biblical notes and the distinct identification of Darius the Great in the Aryan language on Behishtan clearly distinguishes him from, and helps clarify, the origins of Darius the Mede, Emperor of Media, a lesser-known figure of the era also mentioned in the biblical book of Daniel.

After General Ugbaru (Gobyrus in the Greek) conquered Babylon in 539 b.c. on behalf of Cyrus the Great, Cyrus’ uncle, Darius the Mede, took the Jewish prophet Daniel from the city to his capital, Ecbatana, where Daniel was given the role of prime minister of the Medo-Persian Empire after surviving his consignment to the lions’ den. Daniel placed a copy of Cyrus’ decree to rebuild the Jewish Temple in the palace at Ecbatana (see Ezra 6:2), and protests in Judea over the enactment of the decree occurred until Darius the Great took the throne of Medo-Persia in 522 b.c. (see Ezra 4:6).

The next verse in this biblical book applies the uniquely Median generic title, Ahasuerus, to Darius’ grandfather. This derivative of aha-shverous from the Aryan (Old Persian) language is similar to that on the Behishtan Inscription. It signalled the attack by Ahasuerus, the Medes’ father King Cyaxares, on the Scythian King Madius, who had occupied the Median throne from 635–633 b.c. The victory firmly established the kingdom of the Medes, which Darius the Great tore down 100 years later to establish Persian dominance of the empire.

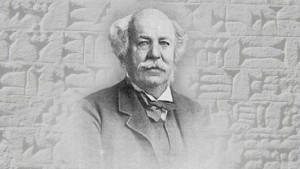

The ancient Aryan language quickly fell into disuse after Darius’ rule and has been described as “forgotten.” However, when the British East India officer, Sir Henry Rawlinson, was assigned to the army of the Shah of Iran in 1835, he climbed the monument, copied the most accessible Old Persian (Aryan) account, and began to decipher it using the syllabary of the Danish linguist, Georg Friedrich Grotefend. Rawlinson’s translation was then applied to the other two languages on the document. He decoded the Akkadian in 1852, enabling the translation of clay tablets from the ancient city of Nineveh and helping to create the discipline of Assyriology.

In 2010, Hamma Mirwaisi, an Iraqi Kurd exiled to the US, realised the Old Persian (Aryan) on Behistan closely resembled his native dialect and compiled a more accurate translation of the text. He discovered that from around 750 b.c., a common language was used by the Medes (the Kurds’ forebears), Persians and the Elamites in the Airyanem Vaejah (land of the Aryan people); the Median, Achaemenid, Parthian and Sassanid empires. With that discovery, Mirwaisi brought unprecedented knowledge and understanding of this seminal Aryan language. His translation affirmed historians’ conclusions that the Aryan text on the Behishtan Inscription, was very similar to the language of the surviving Zoroastrian religious texts of the Avesta. It’s now known that Aryan is very much alive and active in the Middle East where it is spoken by segments of today’s Kurdish population. For example, words still used in Iraq and Iran appear in the text on the cliff face, while adam, the term for “mankind,” links another of the oldest living languages to English and Hebrew.

in the Behishtan Inscription, Darius declared his al- legiance and indebtedness to the singular, uncreated god of light and wisdom, Ahura Mazda, and celebrated his rule over an empire stretching from Armenia in the north, south to Egypt; west to Cappadocia (in today’s Turkey) and east to the border with India. Darius’ elimination of all his competitors, including the rightful heir, Bardiya, son of Cyrus the Great and brother of Cambyses II, was intended to attack three royal lines: the Lydian, the Persian and the Median. However, Bardiya’s grandmother, Aryenis (princess of Lydia, daughter of King Alyattes), was the second wife of Ahasuerus the Mede and their daughter, Princess Mandane of Mede, became Queen Mandane of Persia after her marriage to Cambyses I of Persia. This resulted in only the Median line being destroyed, as per the list above.

Heightened by Darius’ claim that Cambyses II (Bardiya’s brother) later died naturally “of his own hand,” the intrigue then shifted to the mysterious figure of Gautama, who Darius accused of being an interloper and “magiian,” or member of the priestly component of the six Median tribes. His subsequent massacre of the magi advisors to the Median and Persian shahs heralded the moral, spiritual and eventual political demise of both kingdoms. Fortunately, their surviving descendants’ knowledge of astronomy enabled them to follow a guiding star to Judea, where they welcomed the expected Saoshyant or Deliverer in around 5 b.c.

After crossing of the Tigris River on rafts of inflated animal skins on his way to Babylon to investigate a secessionist movement there, Darius’ explanation of how he quelled a potential Babylonian uprising, made revolts throughout the empire in Parsa, Elam, Media, Assyria, Egypt, Parthia, Margiana, Sattagydia and Saka understandable. After subduing them, he systematically sent his military leaders to occupy these regions and keep control.

As Darius advertised his conquests, he took the moral high ground, implying the support of Ahura Mazda, even when entire subject populations rebelled against him. And, although he professed to follow the prophet Zoroaster’s right path of wisdom and knowledge, Darius the Great was in fact the usurper whose merciless propaganda against his enemies ascribes his own brutality to them, including Gautama/Bardiya.

Enforced by violence and complete subjection of all opposition, Darius’ political ambitions saw the end of the benevolent Median Empire and its partnership with the Persians. Wracked by hostility ever since, the relationship between the two Aryan peoples has never been restored. But with some repairs and much deserved respect, the Behishtan Inscription remains to tell the story of the end of the Semitic Neo-Babylonian age and the downfall of its allies, the Aryan Medes of the Zagros Mountain plateau. It demonstrates how the conflict between the descend- ants of the Medes, the Persians and the Babylonians, first documented on the cliff face of Behishtan, continues to this day.

* Historical timelines in antiquity are not absolute. While ARCHAEOLOGICAL DIGGINGS does not agree with all of the Medo- Persian chronology laid out in this article, we have included it, as we believe you will find the article both fascinating and informative.