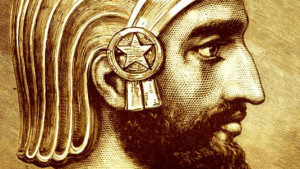

Cyrus II, or Cyrus The Great as he is generally known, was founder and kind of the mighty chaemenian, or Persian, Empire. His father was Cambyses I and, according to Greek historians, his mother was one Mandane, daughter of Astyages, king of Media. After 559 bc, he united the various Persian tribes into one nation and between 553 and 550 bc defeated his grandfather Astyages and took over the Median Empire.

On hearing of the fall of Astyages, Croesus, king of Lydia in Asia Minor (Anatolia), enlarged his dominion at the expense of the Medes. Cyrus, as successor of the Median king, marched against Lydia and captured Sardis, the Lydian capital in 547 bc. The Ionian Greek cities on the Aegean Sea coast, as vassals of the Lydian king, then became subject to Cyrus. While most of these Greek city-states submitted peacefully, several revolts were suppressed with some severity, thereby making Cyrus ruler of all of Asia Minor or Anatolia.

Cyrus next turned to the Babylonian empire. Dissatisfaction of the people with their ruler, Nabonidus, gave Cyrus a pretext for an invasion. The conquest was quick, for even the priests of Marduk had become estranged from Nabonidus. Babylon, the greatest city of the ancient world, fell without a real battle to the Persians in October 539 bc.

Cyrus had several “capitals.” One was the city of Ecbatana (modern Hamadan), the former capital of the Medes, and another was the new capital of the empire, at Pasargadae in Persia. It was said to have been built on the site of Cyrus’s defeat of Astyages, but there are few ruins of Pasargadae to see today. Cyrus also kept Babylon as his winter capital.

Cyrus not only conciliated the Medes, but united them with the Persians in a kind of dual monarchy of the Medes and Persians—Medo-Persia. He borrowed the traditions of kingship from the Medes, who had ruled an empire when the Persians were merely their vassals. A Mede was probably an adviser to the Achaemenian king, a sort of chief minister. Reliefs at Persepolis, a capital of the Achaemenian kings from the time of Darius, frequently depict a Mede together with the king. The Elamites, the indigenous inhabitants of Persia, appear to have had considerable influence over the Persians, as seen, for example, in the Elamite dress worn by Persians and by Elamite objects carried by them that are depicted on the stone reliefs at Persepolis.

Cyrus established a government for his empire in which governors (satraps), who represented him in each province, were responsible for the administration, legislation and cultural activities of each province. And according to Xenophon, Cyrus also devised a postal system; the world’s first.

When he died in a campaign against the tribes in eastern Iran in 530 bc, the world lost one of its greatest monarchs, since he was not only a mighty warrior and a wise organiser but also a tolerant, generous and magnanimous ruler. At the time of his death, his Medo-Persian Empire reached from the Aegean Sea in the west to India in the east, and from the border of Egypt in the south to the Caucasus Mountains in the north. After his death, his son and successor to the throne, Cambyses, added Egypt to the empire, an event probably planned for by Cyrus himself.

Cyrus and Israel

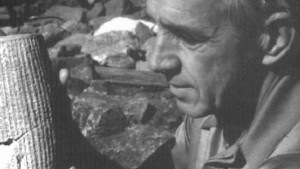

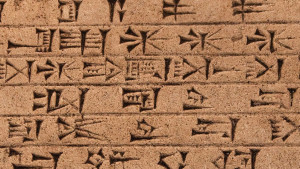

Evidence of Cyrus’s enlightened reign is apparent from the record contained in the Cyrus Cylinder, discovered in Babylon in 1879. In 2010, the British Museum reported that two inscribed clay fragments found at Dailem near Babylon, which had been in its collection since 1881, had been identified as part of a cuneiform tablet inscribed with the same text as the Cyrus Cylinder. And in 1985, the Beijing Palace Museum acquired a horse bone discovered in China inscribed with cuneiform inscriptions apparently derived from the cylinder. Irving Finkel, curator in charge of the British Museum’s Department of the Middle East, has suggested that the cylinder’s text (or even the original cylinder itself) was sent around the Persian Empire and at some point was copied to make the bone inscription. In the cylinder, Cyrus allows the exiled nations of Babylon to return to their homelands with their gods and to rebuild their temples. Note Irving Finkel’s translation of part of the cylinder:

I am Cyrus, king of the universe, the great king, the powerful king, king of Babylon. . . . I collected together all of their people and returned them to their settlements, and the gods of the land of Sumer and Akkad which Nabonidus—to the fury of the lord of the gods—had brought into Shuanna, at the command of Marduk, the great lord, I returned them unharmed to their cells, in the sanctuaries that make them happy. May all the gods that I returned to their sanctuaries, every day before Marduk and Nabu, ask for a long life for me, and mention my good deeds . . .

In view of such words, one can understand why the Cyrus Cylinder might well be considered the world’s first declaration of human rights.

Cyrus is mentioned by name some 22 times by biblical writers, in the books of 2 Chronicles, Ezra, Isaiah and Daniel. While the Jews are not specifically mentioned on the Cyrus Cylinder, it nevertheless confirms what is recorded in the Bible:

Thus says Cyrus king of Persia: All the kingdoms of the earth the Lord God of heaven has given me. And He has commanded me to build Him a house at Jerusalem which is in Judah. Who is among you of all His people? May the Lord his God be with him, and let him go up!” (2 Chronicles 36:23, NKJV)

The similarity of this with Cyrus’s decree mentioned by Ezra, and which he says was also found, by order of Darius I, among the Persian archives at the Palace Achmetha or Ecbatana (Ezra 1:2–4; 6:2–5), reveal them to be an accurate historical record of official documents.

But there exists more than just a historical record of Cyrus’s interaction with Israel by the Bible writers. The biblical prophecies warned that Israel would be deported en masse to Babylon, but they also state that eventually Babylon would be brought down, allowing them to return to Jerusalem (Isaiah 39:6, 7; 43:14; 44:26; 47:1; 48:14, 20). It is in this context that the prophet Isaiah astoundingly names Cyrus as the instrument to bring these events to fruition. Notice the prophecy made about 100 years before the birth of Cyrus and 150 years before his conquest of Babylon:

“This is what the Lord says . . . of Jerusalem, ‘It shall be inhabited,’ of the towns of Judah, ‘They shall be rebuilt,’ and of their ruins, ‘I will restore them,’ who says to the watery deep, ‘Be dry, and I will dry up your streams,’ who says of Cyrus, ‘He is my shepherd and will accomplish all that I please; he will say of Jerusalem, “Let it be rebuilt,” and of the temple, “Let its foundations be laid” ’ ” (Isaiah 44:24–28).

“This is what the Lord says to his anointed, to Cyrus, whose right hand I take hold of to subdue nations before him and to strip kings of their armour, to open doors before him so that gates will not be shut: I will go before you and will level the mountains; I will break down gates of bronze and cut through bars of iron. I will give you hidden treasures, riches stored in secret places, so that you may know that I am the Lord, the God of Israel, who summons you by name. For the sake of Jacob my servant, of Israel my chosen, I summon you by name and bestow on you a title of honour, though you do not acknowledge me. I am the Lord, and there is no other; apart from me there is no God. I will strengthen you, though you have not acknowledged me, so that from the rising of the sun to the place of its setting people may know there is none besides me. I am the Lord, and there is no other. . . . I will raise up Cyrus in my righteousness: I will make all his ways straight. He will rebuild my city and set my exiles free, but not for a price or reward, says the Lord Almighty” (Isaiah 45:1–6, 13).

“Remember the former things, those of long ago; I am God, and there is no other; I am God, and there is none like me. I make known the end from the beginning, from ancient times, what is still to come. I say, ‘My purpose will stand, and I will do all that I please.’ From the east I summon a bird of prey; from a far-off land, a man to fulfil my purpose. What I have said, that I will bring about; what I have planned, that I will do” (Isaiah 46:9–11).

Note in these passages the very specific things Isaiah predicted about Cyrus some 150 years before his conquest of Babylon and also what the prophet Jeremiah (some 50 years before) also predicted about the same things:

1. Cyrus is mentioned by name. The prophet Jeremiah (51:11), some 50 years before Babylon’s conquest by Cyrus, though not mentioning Cyrus by name, also predicted that a Median king would be the instrument to conquer Babylon.

2. Cyrus is to bring about the release of Israel from Babylon and their return to Jerusalem. Again, Jeremiah (25:11,12; 29:10) also predicted that the Jews would be returned to Jerusalem and their fortunes restored, after 70 years of captivity.

3. Cyrus is to facilitate the rebuilding of Jerusalem and its temple. Jeremiah (33:7) also predicted the rebuilding of Jerusalem after the return of the exiles.

4. Israel’s return and the restoration of Jerusalem is to take place in association with the drying up of waters/rivers. Jeremiah (50:38; 51:35, 36) likewise predicted the drying up of Babylon’s waters in relation to its fall.

5. In Cyrus’s conquest, city gates will be left open.

History, as recorded in the Nabonidus Chronicle, on the Cyrus Cylinder, by the Greek historians Herodotus (484–425 bc) and Xenophon (430–354 bc), and in the writings of the sixth century bc Jewish prophet Daniel (chapter 5), records the fulfilment of each of these specific predictions. The fifth chapter of Daniel is now regarded by scholars as ranking next to the Babylonian cuneiform literature in its accuracy. This is due to the fact that Daniel mentions Belshazzar as the king of Babylon at its conquest, a fact supported by Babylonian cuneiform documents. He also records that a drunken festival was taking place at the time of its fall, a claim supported by both Herodotus and Xenophon.

The Nabonidus Chronicle informs us that Cyrus invaded Babylonia in 539 bc and routed the Medo-Persian army at the Battle of Opis. According to Herodotus and Xenophon, in October of that same year, soldiers of Cyrus, under Gobryas, besieged the city. Finding its walls impregnable, the Persians diverted the course of the Euphrates River so that it dropped to a level whereby the Persian army was able to wade along the riverbed, under the walls at the points where the river entered and exited the city. This occurred at the time of a festival during which the Babylonians left the gates of the walls along the bank of the river open, and since the residents, and to some extent the guards, of the city were distracted by the revelry of the festival, the nocturnal activities of the Persians went undetected and they conquered the city.

The fifth chapter of Daniel records that during Belshazzar’s feast, the forces of Cyrus took the city and killed the king. Xenophon supports Daniel’s assertion. Daniel also indicates the quick fall of Babylon, as do the Nabonidus Chronicle, the Cyrus Cylinder, Herodotus and Xenophon.

While the Cyrus Cylinder makes no mention of the Jews specifically, it does reveal that he allowed Babylonian captives, among whom of course were the Jews, to return to their homelands and rebuild their temples and restore their national forms of worship, thus supporting the claims of the writer of 2 Chronicles and Ezra that Cyrus allowed Jewish captives to return from Babylon to Jerusalem and rebuild the Temple. Consequently, the cylinder contains confirmation of Isaiah’s prediction that Cyrus would be the instrument for returning the Jews to Jerusalem and rebuilding their temple.

In light of such incredible fulfilments of Isaiah’s predictions, one can understand why higher critical scholars, who do not believe in prophetic foreknowledge and the supernatural in general, might wish to undermine Isaiah’s prophecy of Cyrus by suggesting that the book of Isaiah had at least two authors, who wrote in different time periods—a so-called “first Isaiah,” who wrote chapters one to 39 at the close of the eighth/early seventh century bc, and a “second Isaiah” or Deutero-Isaiah, who wrote chapters 40 to 66 (which contain the prophecies about Cyrus) after 539 bc, when the so-called predicted events would already have occurred. Some critics even assign the second half of the book to the Maccabean period, which is the second century bc and well after the events outlined.

However, scholarship quickly reveals the fallacy of such suggestions, demonstrating that the book had only one author who wrote it in the late eighth/early seventh century bc. The evidence for this includes the following:

1. There are many evidences of unity of thought and expression throughout the book of Isaiah. For example, a characteristic of Isaiah is his use of the term “the Holy One of Israel” as one of God’s titles. It occurs 25 times in the book and only six times in the rest of the Old Testament. However it is found 12 times in chapters one to 39 (the section nearly all scholars believe was written at the close of the eighth/early seventh century bc) and 13 times in chapters 40 to 66. The title “the mighty One of Israel (or ‘of Jacob,’ another name for Israel)” is found only in the book of Isaiah and again in both sections (Isaiah 1:24; 30:29; 49:26; 60:16). Similarities of style and language between the two sections of Isaiah are much more impressive than its supposed differences.

2. The arching theme of both sections of the book is “deliverance.” Chapters one to 39 present Jewish deliverance from sin, from Syria, Assyria and their other enemies, through repentance, reformation and renewed faith in God. Chapters 40 to 66 anticipate captivity in Babylon, but with the assurance that eventual deliverance will be as certain as that which was (then) recently experienced from Assyria during the time of Hezekiah. But more than that, eventually there will be deliverance from sin’s dominion through faith in the coming Deliverer or Messiah. Thus, while there are apparent differences in subject matter between the two sections, a fundamental unity of thought and purpose pervades the whole book.

3. As mentioned, some critics have assigned a significant portion of the book of Isaiah to the Maccabean period (167–160 bc). However, there is evidence that the entire book already existed as one unit before that time, for writing about 180 bc, Jesus ben Sirach, the author of the apocryphal book of Ecclesiasticus (chapter 48:23–28), credited various sections of the book of Isaiah to the prophet whose name it bears.

4. But the best evidence that centuries before Christ the book of Isaiah was regarded as a single unit comes from two scrolls of Isaiah found in 1947 among the Dead Sea Scrolls. In both scrolls there is no evidence whatsoever that chapters one to 39 existed independently from chapters 40 to 66. Rather, the evidence is to the contrary, indicating that Isaiah the prophet authored all chapters in the late eighth/early seventh century bc, at least some 150 years before the events predicted concerning Cyrus.

5. The New Testament writers and characters such as Jesus and the apostle Paul accepted the book of Isaiah as a single unit without any hint of distinctions between the two sections.

6. According to Josephus (Antiquities 11.1.2), Cyrus read the prophecies left behind by Isaiah concerning himself, which Josephus says were written 140 years before the Temple was destroyed by the Babylonians.

7. Critics claim chapters 40 to 66 were written by a second Isaiah in exile in Babylon, yet: the cities had not yet been destroyed (Isaiah 40:9; 62:6); he excoriates unjust judges in Israel, implying that the government is still in operation (Isaiah 58:6); and the geography, flora and fauna mentioned are those of Palestine not Babylon (Isaiah 41:19; 44:14). The unmistakable conclusion is that it was composed in Palestine rather than in Babylon.

8. The post-exilic prophets (Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi, Ezra and Nehemiah) never mention idolatry as a sin after the exile. Yet, if as critics assert, chapters 40 to 66 were written in Babylon or late-dated in Israel after the return from exile, why does the author denounce idolatry (44:9-20; 57:4–5, 7; 65:2–4) so vehemently in this section? Such denunciation would be senseless after the exile, but makes perfect sense before it.

Clearly all of Isaiah was written by the same person in the late eighth/early seventh century bc. But what was the purpose of Isaiah’s prophecy concerning Cyrus and his activities in relation to Israel? Ironically, it was just the opposite of that of the critics, whose ultimate purpose has been to deny the supernatural.

The purpose of the prophecy is threefold: First, that Cyrus will know that the Lord is the God of Israel; second, for Israel’s sake, to bring them hope that they will be delivered from Babylon (through Cyrus); and, third, so the world (“from horizon to horizon”) will know that the Lord is God. Note how this is emphasised in the Isaiah prophecy about Cyrus: “Thus says the Lord . . . Who says to the deep, ‘Be dry! And I will dry up your rivers’; Who says of Cyrus, ‘He is My shepherd, and he shall perform all My pleasure, saying to Jerusalem, ‘You shall be built,’ and to the temple, ‘Your foundation shall be laid.’

“Thus says the Lord to His anointed, to Cyrus, whose right hand I have held . . . to subdue nations before him . . . to open before him the double doors, so that the gates will not be shut . . . that you [Cyrus] may know that I, the Lord, Who call you by your name, am the God of Israel. For Jacob My servant’s sake, and Israel My elect, I have even called you by your name; I have named you, though you have not known Me. I am the Lord, and there is no other; There is no God besides Me. I will gird you, though you have not known Me, That they may know from the rising of the sun to its setting that there is none besides Me. I am the Lord, and there is no other” (Isaiah 44:24, 26–28; 45:1, 3–6, NKJV, italics added).

It is very clear from the above that one of the purposes of this prophecy is that Cyrus and the rest of humanity might know there is indeed a god, and only one God—the Lord. In fact, as one continues to read this “Cyrus prophecy,” it is clearly the purpose of biblical prophecy in general: “Remember the former things of old, for I am God, and there is no other; I am God, and there is none like Me, declaring the end from the beginning, and from ancient times things that are not yet done, saying, ‘My counsel shall stand, and I will do all My pleasure,’ calling a bird of prey from the east, the man [Cyrus] who executes My counsel, from a far country. . . . I have spoken it; I will also bring it to pass. I have purposed it; I will also do it” (Isaiah 46:9–11, NKJV, italics added).

This same purpose of predictive prophecy—to believe in God—was also a stated purpose of predictions made by Jesus (John 13:19; 14:29). Little wonder higher criticism, which has no place for the supernatural, whose philosophy is based on human rationalism and naturalism, has sought to relegate this prophecy to a period after the events it refers to. If it were to have been composed in the late eighth/early seventh century bc—150 years before the predicted events—it would completely undermine their world view.