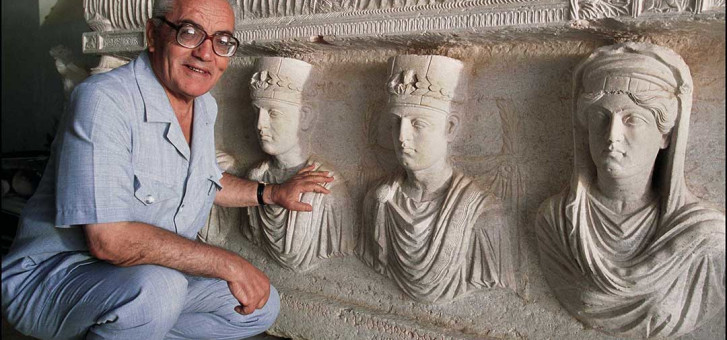

I first got to know Khaled al-Asaad in the 1980s as a colleague, and subsequently as a long-standing friend. During my almost annual visits to Syria until 2008, I could always count on the warmest of welcomes at Palmyra, and I well recall Khaled, standing on the steps of the Tadmor Museum, his face beaming, ushering me into his tiny office and sweeping piles of papers on to the floor in an attempt to excavate a chair for me.

His enthusiasm for Palmyra was inextinguishable and, within minutes of my arrival, I would be immersed in plans, drawings and photographs of the latest research.

His heartless murder has come as a great shock and he will be greatly missed.

Khaled was an outstanding scholar, a world expert on the history and archaeology of Palmyra, the site that was his passion to which he devoted much of his long and dedicated working life. There will surely be few people who visited this world heritage site who do not have on their bookshelves a copy of his book, Palmyra: History, Monuments and Museum (co-authored with Adnan Bounni), which became the definitive guidebook almost immediately after its publication in 1982.

Yet his scholarship was much deeper and he was a regular contributor to Les Annales Archéologiques Arabes Syriennes (the journal of Syria’s Directorate General of Antiquities and Museums) with articles on all aspects of Palmyrene culture, especially those relating to the extraordinary series of funerary portrait busts and their associated inscriptions.

Khaled was a delightful person, with a warm and engaging personality and a wry sense of humour. He went to great lengths to welcome and assist scholars, students and visitors from around the world and his book-cluttered office in the Tadmor Museum was regularly full of a whole variety of people enjoying his tea and his company. As director of Palmyra, he encouraged and facilitated research, excavation and restoration and, at the same time, made it accessible for tourists as surely one of the most impressive and unforgettable archaeological sites in the world.

Built around a natural oasis, this ancient caravan city sat proudly on one of the main trade routes from the Mediterranean to the Euphrates and from there to markets further east. The city was also the capital of the famous third-century Queen Zenobia, who dared to challenge the power of Rome. With its colonnaded streets, monumental arch, tetrapylon (a kind of crossroads monument), theatre, numerous temples (including the enormous Temple of Bel, dedicated to the Semitic god of the same name) and the Valley of Tombs, it is one of the most impressive and beautiful of the Unesco World Heritage sites.

Khaled was particularly interested in the funerary monuments built outside the city for its wealthier citizens: tomb towers of several storeys, the earliest examples dating back to Hellenistic times; single-storey house tombs; and underground rock-hewn tombs called hypogea.

All of these tomb types contained compartments (loculi) set into the walls to hold the remains of the dead and each loculus was sealed with a plaque bearing a sculptural portrait of the deceased and a brief dedicatory inscription. It was these fascinating and highly individual busts that captured Khaled’s imagination and it is the research he undertook in respect of them that will remain an invaluable contribution to our understanding of Palmyra and its unique culture.

In 2003, Asaad was part of a joint Syrian-Polish archaeological team to unearth an intact third-century mosaic depicting a battle between a human being and a mythical winged animal, and surrounded by geometric drawings of grapes, figs, deer and horses. At the time, he described the 70-square-metre (83 square yards) mosaic as “one of the most precious discoveries ever made in Palmyra.”

Asaad is the highest profile scholar to be murdered by ISIS to date. His alleged crimes included representing Syria at “infidel conferences,” serving as “the director of idolatry” in Palmyra, visiting Iran to commemorate the anniversary of the “Khomeini revolution” and communicating with Syrian military officers, including his brother Col. Issa al-Asaadin.

The event has highlighted the terrorist group’s increased looting and selling of antiquities to fund its activities, in addition to destroying them (see “Looted in Syria, Sold in London,” ARCHAEOLOGICAL DIGGINGS, September-October 2015). In June 2015, prior to Asaad’s arrest and subsequent execution, ISIS blew up two ancient shrines in Palmyra that were not part of its Roman-era structures but which the militants regarded as pagan and sacrilegious. And in July 2015, it released a shocking video of the execution of 25 captured government soldiers in Palmyra’s Roman amphitheatre.

Destroying History

Before the arrival of Christianity in the second century a.d., Palmyra worshipped the Semitic god Bel, along with the sun god Yarhibol and the lunar god Aglibol.

So far Islamic State (ISIS) militants have destroyed the Roman Arch of Triumph, the Temple of Bel, once the centre of religious life in ancient Palmyra, and the historic Temple of Baalshamin. The militants also beheaded Khaled al-Assaad, after he refused to pass on the location of hidden artefacts.

ISIS' strict interpretation of Islam sees the preservation of ancient artefacts and monuments to be a form of idolatry, although they also profit from illicitly selling artefacts they loot from ancient sites

Condemning The Destruction

Extremists “cannot silence history,” the Director-General of United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Irina Bokova, has defiantly declared in her condemnation of the destruction of Palmyra’s ancient Temple of Baalshamin, in Syria, a World Heritage site.

“The systematic destruction of cultural symbols embodying Syrian cultural diversity reveals the true intent of such attacks,” Bokova said, “which is to deprive the Syrian people of its knowledge, its identity and history.” She went on to declare it “a new war crime,” stating that such acts and their perpetrators will be held accountable for their actions.

According to UNESCO, Baalshamin Temple was built nearly 2000 years ago, and bears witness to the depth of the pre-Islamic history of the country. Its cella, or inner area, was severely damaged, and followed by the collapse of the surrounding columns. The structure of the Baalshamin Temple dates to the Roman era. It was erected in the first century a.d. and further enlarged by Roman emperor Hadrian. The temple is—or was—one of the best preserved buildings in Palmyra.

This ancient city, famed for its Greco-Roman monumental ruins, had repeatedly been targeted by Da’esh (ISIS) since May 2015.

Said Bokova, “Extremists seek to destroy this diversity and richness, and I call on the international community to stand united against this persistent cultural cleansing. Da’esh is killing people and destroying sites, but cannot silence history and will ultimately fail to erase this great culture from the memory of the world. Despite the obstacles and fanaticism, human creativity will prevail, buildings and sites will be rehabilitated, and some will be rebuilt.”

– UNESCO