By ascending an old spiral staircase in present day Jerusalem, winding up against the ancient ramparts of the Old City you can arrive at an unassuming metal door which enters onto a world which has been lost for millennia. The experience has all the hallmarks of the recent television series Dig which starred Jason Isaacs and Anne Heche; a story which began behind an inconspicuous door on an unassuming back street in Old Jerusalem.

However, unlike its fictional counterpart, nothing sinister lies behind the door at which you arrive. Rather, you gain entry to a long, narrow building; to all intents and purposes an encyclopaedia of Jerusalem’s past. It contains an excavation, a forensic time-line of the city extending back almost 3000 years, from the time of the First Temple to the British Mandate. And it tells a more compelling story than any fictional TV drama.

Hidden from public view for decades, these revealing excavations have just been opened to the general public. The excavations are spectacular in that they catalogue Jerusalem’s long and colourful history, layer upon layer; nowhere else in Jerusalem is this so evidently clear as in this small space.

The Kishle Building, as it is called, stands adjacent to the Tower of David, the ancient citadel that guards Jerusalem’s Old City at the Jaffa Gate entrance. It was built in 1860 as an Ottoman prison or army barracks. The prison was then used as such by the British during Mandate times and then left desolate until the Tower of David Museum decided to clean up the iron prison cells and create a new wing for the Education Department. It housed members of the pre-State underground, the Irgun, the evidence of which is scratched on the walls.

As with any digging in Jerusalem, the clearing up became an excavation and close to 3000 years of history was discovered under its floorboards. The excavations were carried out in 1999–2000 by Amit Re’em, Jerusalem District Archeologist, together with a team from the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA), but since then the building has been left untouched. Entrance to the Kishle is via the newly opened moat where visitors walk down the impressive Herodian steps leading down into a Hasmonian pool that would have been the lavish pool connected to King Herod’s palace. (These are the only excavations of King Herod’s Palace; huge foundation walls can be seen as well as an impressive water sewage system.)

The whole site has been dug down some 10 metres (33 ft) deep and about 50 metres (165 ft) long to reveal the various strata. With an arched, cross-vaulted Ottoman ceiling, it is a cavernous, silent cathedral of ancient stones that had been untouched by daylight for millennia.

The "Kishle"

The term Kishle refers to a prison in Ottoman Turkish, as it was used as a detention centre during Ottoman rule. It is an impressive 450-m (1475 ft) arched structure. Like the Citadel itself, the Kishle is built on an area formerly part of the Herodian Palace, later the residence of the Tenth Roman Legion, followed by the castle of the Crusader King of Jerusalem.

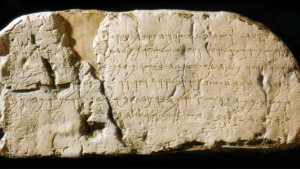

The Kishle is one of the most fascinating hidden spaces in the Tower of David Museum compound, an underground space that spans the history of Jerusalem. The Kishle building was built in 1834 by Ibrahim Pasha, the Egyptian ruler, and continued to serve as a military compound even after it was returned to Ottoman control in 1841. Within the walls of this unique building, there is physical evidence that creates a time line spanning Jerusalem’s history, from most “recent times,” from the Irgun graffiti of the British Mandate, to tanneries and dying pools in the Middle Ages, to two massive walls from the Herodian period, an ancient drainage system that transported sewage from King Herod’s palace to outside the city walls, as well as parts of the Hasmonean city wall and even a wall from the time of King Hezekiah.

The Moat

As was common in most citadels, in particular those built during the Middle Ages, the citadel in Jerusalem (better known as the Tower of David) was also surrounded by a moat. Although the Citadel moat has been closed to the public for many years, now the southern part of it’s historic moat has been opened. The moat is a wide ditch surrounding the foundations of the citadel and was designed as the first line of defence, preventing an enemy entering from the foot of the fortress. Unlike European moats that were flooded with water, the moat in Jerusalem’s citadel is a dry moat. A drawbridge that leads up to the main entrance gate of the citadel crosses the moat. The moat also contains a passage to the Kishle. During the Ottoman rule and under the instruction of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, a most impressive gate led to the large entrance plaza of the citadel. An outdoor mosque was built alongside the plaza and this new structure cut the moat into two parts. As time went on, the moat was filled with debris and became neglected. During the British Mandate, the area was given to the city’s residents and the land was used for growing vegetables and an ornamental garden was also added.

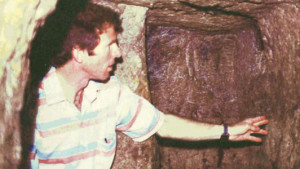

It was in the 1980s that extensive archaeological excavations were conducted in the moat as part of the preparation for transforming the citadel into the Museum of the History of Jerusalem. Among the litter of past gen- erations, mundane items such as buttons from Turkish army uniforms, broken coffee cups, moustache wax andclay smoking pipes were found.

Once the debris had been cleared out, the bottom of themoat was in full view and truly exciting archaeological discoveries were made. These excavations uncovered evidence of much earlier and grander eras.

Flavius Josephus recounts that King Herod built his palace on the site and that it contained extensive gardens and buildings. Excavations in the moat have brought to light 20 monumental steps that lead to an enormous double pool carved into the rock, which was part of the royal compound built by Herod. It is likely that Herod built his magnificent residence on the site of the palace of the Hasmonean kings, who made Jerusalem the capital of their kingdom. Hundreds of coins from the Hasmonean period were discovered in the plastered canals that brought water to the pools. In addition, Seleucid coins were found underneath the pools themselves. A ritual bath (mikve) from the Hasmonean period was also revealed nearby. It is assumed that this mikve was originally located in a wing of a Hasmonean palace. A large quarry was also uncovered in the moat. The quarry may be from the First Temple (Israelite) or even Canaanite period, and appears to have been abandoned in haste. One can still discern large cut stones, not yet removed from the bedrock, and the imprints of stones already quarried. It is likely that this quarry supplied the materials for the monumental buildings of ancient Jerusalem. A wall built of large field stones crosses the quarry. Dated to the time of the kings of Judah, it is similar in composition to the Broad Wall from the days of the First Temple that can be seen in the Jewish Quarter of the old city today.

The importance of these findings are three-fold: first, these are the only excavations from King Herod’s palace; second, the eighth century B.C. wall shows the parameters of the city in the times of the First Temple Period; and, third, there is no other place where layer upon layer of Jerusalem’s history can be felt so strongly. Now the Moat and Kishle are open to the general public, with twice-weekly guided tours in English, a must-see for the serious or amateur historian or archaeologist alike, and a definite for the curious tourist.