The Nile River in ancient Egypt was the vital link to many facets of this ancient culture and was never far from the sight of the people who lived in settlements within a short distance of its banks. It provided the dietary staple of fish and waterfowl; papyrus for ropes, rafts, writing implements and footwear; encompassed the agriculture, religion, culture and transport in Egypt; and its life-giving nature was celebrated with festivals. the Nile was also essential in transporting blocks of stone from the quarries to the building sites of temples, cemeteries and the pyramids.

Despite the Nile being synonymous with both ancient and modern Egypt, only 22 per cent of this mighty river is situated in Egypt itself. The north-flowing Nile meanders through 11 countries from East Africa to the Mediterranean: Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Congo-Kinshasa, Kenya, Ethiopia, Eritrea, South Sudan and Sudan, before fanning out through Egypt and emptying into the Mediterranean Sea. Two main branches of the Nile are formed in the delta with the Rosetta to the west and Damietta at the east. In ancient times, there were three branches, identified as the water of Pre, the water of Ptah and the water of Amun.

The hydrographic basin of the Nile is immense, covering 3.2 million square kilometres and with a length of some 6740 kilometres (4190 miles). Including the remotest source at the Kagera River in Burundi, it is also the world’s longest river. The summer monsoons in Ethiopia initiate a large portion of the Nile that is carried north. There are six cataracts, or rapids, formed by rocky outcrops that are sited in the southern section of the Nile between Aswan and Khartoum, and until the New Kingdom (1550 B.C.), this formed the boundary of the Egyptian empire. After this time, in the quest for gold and new lands, this southern boundary was opened up for exploration.

There are three rivers from the south that join into the Nile, The White Nile, The Blue Nile and the Atbara. Viewed from high above, the Nile at the delta forms a fan shape with its canals resembling an open lotus plant and the Nile itself as the stem of the flower. This is rather apt for a civilisation that held the newborn sun emerging from a lotus plant as one of its creation myths.

The site of the Nile in Egypt today is not at the same area or size as it was in ancient times as it is moving laterally, evidenced from core samples, levees, migra- tion studies, NASA satellites and infra-red imagery. By its very nature, as the waters shifted and altered slowly over the millennia, it covered and flooded much earlier habitations including, unfortunately, some aspects of the predynastic and other eras.

The Religion of The Nile

In a land that almost never rains, the Nile in ancient Egypt was essential and considered a god-created element of the universe. For an empire that seemed to have a different god relating to all aspects of daily life and the afterlife, it is unsurprising that the Egyptians also worshipped a god of the Nile, more specifically to the yearly inundating Nile. The inundation was separate to the River Nile and personified as the god Hapy (or Hapi). He was represented as a bearded, plump man with drooping breasts and wearing a headdress of aquatic plants, with his image relating to fecundity and fertility. Some images show two Hapys, one representing Lower Egypt with a lotus headdress and the other signifying Upper Egypt, with its symbol of the papyrus, and together they bind the sema-hieroglyph, depicted as a windpipe. This binding action is significant as it indicates the uniting of Upper and Lower Egypt. Festivals honouring Hapy were held in appreciation of the yearly inundation and hymns were recited or sung. An example is the “Hymn to Hapy,” also known as “Hymn to the Nile,” reproduced here in part:

Hail to you Hapy,

Sprung from earth,

Come to nourish Egypt!

Of secret ways,

A darkness by day,

To whom his followers sing!

Who floods the fields that Re has made,

To nourish all who thirst;

Let’s drink the waterless desert,

His dew descending from the sky. (Lichtheim 1975, p. 205)

At the site of Gebel el-Silsila, a rocky sandstone outcrop between Edfu and Kom Ombo, the Pharaoh Seti I of the New Kingdom (1279–1213 B.C.) had an inscription of the “Hymn to Hapy” carved into the rock in a shrine. The worship of Hapy continued to be observed by his son, Rameses II, and grandson, Merenptah. Other relevant gods are also inscribed on these cliffs in the wish for blessings of the Nile: the crocodile god, Sobek, Tauret the hippopotamus goddess, and the Triad of Elephantine, comprising of Khnum, Satet and Anuket.

In Hadrian’s Arch at the temple of Philae, a bas-relief shows an image of Hapy, hidden in his cave and sur- rounded protectively by a coiled snake. As the god of the inundation, he holds an ewer (a vase-shaped pitcher) in each hand that springs forth water, representing the inundation of both Upper and Lower Egypt.

A nilometer in the temples gave ancient Egyptians the ability to measure the inundation and therefore be prepared for flood, famine or an abundant harvest. Created as a deep well from the water table with stairs up to ground level, as the floodwaters increased up the steps, this allowed the priests to measure the speed of the rising height as well as the general level of the river. By comparisons to previous years’ flood levels, precise records could be kept to assist in agricultural planning. A good flood could enrich the land while one that is too low or high could cause famine or ruin. A nilometer rebuilt in Roman times on Elephantine Island at Aswan has a surviving example, as do the temples of Dendera, Philae Kom Ombo, Edfu and Esna. Pliny the Elder, a Roman historian who wrote Historia Naturalis, wrote about the implication of the Nile level upon agriculture and society:

An average rise is one of seven metres. A smaller volume

of water does not irrigate all localities and a

larger one, by retiring too slowly, retards agriculture . . .

in a rise of five-and-a-half metres it senses famine

and even at one of six metres it begins to feel hungry,

but at six-and-a-half metres brings cheerfulness,

six-and-three-quarters complete confidence and

even metres delight. (Bowman 1996, p. 103)

Death and the Nile

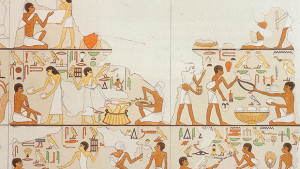

Many ancient Egyptian tombs and temples feature beautiful carvings or paintings of the Nile with fishermen and their nets catching abundant fish, men jousting in papyrus rafts, bird life and even insects living within the marshes. From the tomb of official Nebamun, dating to the later Eighteenth Dynasty (1350 B.C.), are 11 plaster fragments now preserved in the British Museum.

There is significance beyond the glorious artwork of the Nile in his tomb. Central to the image is Nebamun and his wife dressed in their best attire as he strides upon a papyrus skiff, arms raised, hunting birds with a throwing stick, while their daughter sits between his legs. They are surrounded by the bountiful harvest of the Nile: several species of fish, birds and ducks; even the family cat has caught a duck in its mouth and a bird between its paws. Interestingly, Tilapia fish and a Plain Tiger butterfly are identifiable in this marshy Nile setting. Is this just a record of a happy family outing painted on a tomb wall? Depicted as young, strong and beautifully adorned with exotic wigs, this image of the couple is also one of eroticism. The connotation is one of rebirth from the life-giving waters of the Nile and the bountiful marshes, while the tawny cat can be identified with the Sun god overtaking the enemies of order and light.

Conflict at the Nile

A well-documented and decisive battle held on the Nile by the Egyptian navy at the time of Rameses III (1175 B.C.) was against a group called the Sea Peoples, a sea-warring people who had previously invaded Anatolia, Syria, Canaan and Cyprus. The Egyptian navy was quite prepared—if they lost this battle, Egypt would very likely be taken over by another country.

In the mortuary temple of Rameses III, located at Medinet Habu, a relief shows the pharaoh and his army firing thousands of arrows amid the chaos of the ships of the Sea Peoples. The nimbleness of Egyptian craft with its well-equipped archers on the boats and the army on the banks were able to overtake this invasion, ensuring a continued reign under Rameses III.

Transport on the Nile

The movement of people and goods on the Nile was by wooden boats or papyrus bundles fastened together, known as skiffs or rafts. A full sail shown in hieroglyphs indicate that the journey was going downstream to the south, while oars were used for the current heading north. Travelling by boat was not only for transport, trade, hunting and fishing, it also facilitated armies in warfare. Boats were used before the unification of Egypt, and several have been found, notably the reconstructed solar bark of Pharaoh Khufu (2550 B.C.), now housed at the pyramid site of Giza. More recently, Dr Yann Tristant of Macquarie University, Sydney, discovered the earliest funerary boat dating to 2950 B.C. during the reign of Pharaoh Den. (This significant find was reported in the February/March 2014 edition of ARCHAEOLOGICAL DIGGINGS.)

Trees were not abundant in Egypt so wood was traded; indeed the funerary boat of Khufu was constructed of cedar from Lebanon while a boat dating to the earlier era of Den was formed mostly from acacia wood with pieces of tamarisk. Ships intended for the sea were also constructed from cedar wood. Upon the walls of her funerary temple at Deir el-Bahri, the female pharaoh Hatshepsut had images carved of her trading ships return- ing from the land of Punt, considered to be in Somalia. An amazing find of ancient papyrus ropes, believed to be from around 3800 years ago, were found in caves in Mersa (or Wadi Gawasis) in the Red Sea and are likely to have been for such an expedition.

Economy on the Nile

The items that the ancient Egyptians coveted, but were not available in their land, were brought into the empire by the commercialism of trade and diplomacy with other countries. It is here that the Nile was employed as the ferrying agent after the goods were brought overland or from the Mediterranean or Red Sea. Some of the world’s oldest trading routes radiate from the Nile valley, the delta and Nubia, and link with the nearby countries of Greece, the Levant and Mesopotamia.

The Nile: Then and Now

The ancient Nile gave the gift of annual flooding and therefore determined the agricultural seasons of Egypt. This is the foremost difference to modern-day Egypt. The inundation was a yearly flood that covered the banks of both sides with up to two metres of water and lasted from July to October. Ancient Egypt’s calendar was divided into three seasons: the inundation known as Aket, the growing stage, Peret, and the drought, Shemu, that was the resulting harvest season. Canals and locks were used to assist the floodwaters with its rich, fertilising silt and direct it to the cultivatable areas. Irrigation was also assisted by the use of a shaduf (or shadoof), a device to draw water from a well using a high pole with a bucket at the end, and is still in use today, particularly in southern Egypt. The inundation brought the characteristic rich black silt, depositing it over the land after the waters receded and acted as a natural fertiliser. It is also the reason ancient Egypt was known as kmt, or “Black Land.”

Modern Egypt, however, has two seasons: a mild winter from November to April, in contrast to a hot summer from May to October. The perpetual inundation was halted with the building of the Aswan Dam in 1889, but as this failed to effectively hold the water, it was raised again in 1912 and 1933. After these unsuccessful attempts, the Aswan High Dam was constructed in the 1960s. (For a story on the shifting of significant temples due to their impending flood from the dam, see “The Abu Simbel Story,” in the April/May 2014 edition of ARCHAEOLOGICAL DIGGINGS). The Aswan Dam controls the flood, supplies about half of Egypt’s power and maintains a constant water level. Adversely, without the natural silt, the impact has been significant upon agriculture in which it is now necessary to spread significant amounts of phosphates and fertiliser.

However, in most ways, the Nile’s relationship with both ancient and modern Egypt is still relatively the same, bringing life-giving water to this dry land, right down to a waterborne parasite—known by two modern names, bilharziasis or schistosomiasis, a debilitating condition that can lead to death in some instances—that has afflicted humankind for millennia. Although it is treatable, reinfection is highly likely from contact with the waters of the Nile. The evidence for this parasite already being in existence in ancient times lies in the bodies of some mummies, which have also revealed ancient malaria and tapeworm. The Schistosomiasis Project at Manchester University is studying the parasite and it is hoped a modern cure can be found.

The Nile vistas offer the visitor and local alike a timeless and peaceful beauty worthy of praise and ponder, if not for the majesty of the ancient civilisation that lived their everyday life by the grace of it. In the words of Amelia Edwards who wrote the classic A Thousand Miles Up the Nile in 1877, “This reminds me that the traveller on the Nile really sees the whole land of Egypt. It helps one, as nothing else can help one, to an understanding of the wonderful mountain waste through which the Nile has been scooping its way for uncounted cycles. And it enables one to realise what a mere slip of alluvial deposit is this famous land which is ‘the gift of the river.’ ”

Fast Facts

- The Nile River with a total length 6740 km (4190 miles) is the longest river in the world.

- Located in Africa, the Nile and its tributaries flow through Egypt, Zaire, Tanzania, Rwanda, Uganda, Burundi, Ethiopia, Sudan and Kenya.

- The Nile Delta spreads out along 240 kilometres (149 miles) of coastline.

- The two major sources of the river are Lake Victoria in Tanzania, which feeds the White Nile, and Lake Tana, in Ethiopia, which feeds the Blue Nile.

- Ancient Egyptians called the river Ar, which means “black,” because the annual flood left black sediment along its banks.

Sources

-

Borojevic, K. and Mountain, R. (2011) The Ropes of Pharaohs: The Source of Cordage from “Rope Cave” at Mersa/Wadi Gawasis Revisited, JARCE v.47 pp. 131–141.

-

Bowman, A. (1996) Egypt after the Pharaohs. Hong Kong: University of California Press.

-

David, R. and Archbold, R. (2000) Conversations With Mummies. Australia: Allen & Unwin.

-

Edwards,A.(1877)AThousandMilesUpTheNile.London:Routledge & Sons.

-

Guadalupi, G. (2007) the Nile, History, Adventure and Discovery. Italy: White Star.

-

Kami,J.(1993)AswanandAbuSimbel:HistoryandGuide.Egypt: American University in Cairo.

-

Kemp, B. (2000) Ancient Egypt Anatomy of a Civilisation. Great Britain: Routledge.

-

Lichtheim,M.(1975)AncientEgyptianLiteratureVolume1:TheOld and Middle Kingdoms. Berkeley: University of California Press.

-

Parkinson, R. (2008) The Painted Tomb Chapel Of Nebamun Masterpieces of Egyptian Art in the British Museum, London: The British Museum.

-

Shaw, I. and Nicholson, P. (2008) The Illustrated Dictionary of Ancient Egypt. Egypt: The American University in Cairo Press.