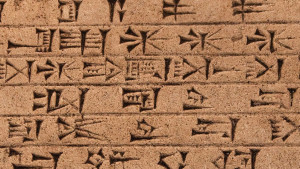

Think of the ancient world and we tend to thikn of the lines on maps as separating empires populations, rather than lines that joined them. And of the latter there was none more important than the Silk Road, so-called, a thread that linked the mysterious East to the more familiar West. This trade route to Asia had a number of variants, which included land and sea options, with both originating at the heart of the then Parthian Empire in the northern Levant, which stretched 12,000 kilometres eastward to China and India.

It’s possible to view the physical remains of the land route, such as the caravanseri—a later addition—dotted at intervals along the route, some in better repair than others, along with its intangible legacy, despite its decline from around the middle of the second millennium AD

The Silk Road flowed with wealth as government-sponsored traders from the East exchanged their wares—gold, cinnamon, skins and, of course, silk raw and woven—for those of the West—wine, linen, horses, woollen goods and exotic plants— along with ideas. And those along its route also were enriched by the taxes levied on the passing trade. Public buildings, like those at Palmyra, which were erected throughout the Middle East in the first and second centuries AD, show just how lucrative that trade must have been. Such was the potential for profit, that although the Romans placed a high 25 per cent duty on all goods arriving from the east via the Silk Road, huge trading ventures not only continued, but flourished.

The Silk Road begins in ancient Parthia. The Parthians came into ascendency in the Middle East in the mid-second century b.c. and soon thereafter, they opened trade with India and China. By mid-first century b.c., they had also commenced trading with another new power that had arisen around the same time as Parthia—Rome across the Mediterranean. A new era of rivalry and ongoing conflict in world trade and international relations had begun. In fact, the first the Romans knew of it was when in 53 b.c., in an attack on Parthia, they noted the beautiful colourful banners of an iridescent material being carried into battle by their adversary. It was, of course, silk. And they wanted some. As the Roman empire grew, so did their demand for this luxurious fabric.

Beginnings

According to the best ancient description available—a record by one Isidore of Charax—the Silk Road stretched all the way from China west to the steppes of Bactria (modern-day Afghanistan), from where it forked south to the Indus River and into India, and west through Persia (present-day Iran) and southern Mesopotamia, and from there, it went north following the Euphrates River and into Palmyra, before crossing to the coast at Antioch and other trading centres throughout Roman Syria. It is estimated that in total the Silk Road extended for some 21,000 kilometres or 12,000 miles—from Luoyang in north China (to Guangzhou, by sea) and Antioch in the west—with a sea extension to Rome.

Intriguingly, Isidore of Charax had an especially im- portant role to play in Roman espionage. Originally from Characene, at the head of the Persian Gulf in present-day Kuwait, Isidore was a Parthian subject living in the late first century b.c. However, when he defected to Rome he became a useful spy. The emperor Augustus Caesar had had designs on the Parthian Empire for some time, and when his two grandsons, Gaius and Lucius, came of age he declared them his heirs and commissioned them to conquer the empire for themselves—and for Rome, of course. But Rome’s repeated failures to conquer Parthia in the past meant that Augustus needed the best intelligence for his grandsons’ invasions to succeed. So, Isidore was engaged to supply intelligence on the inner-workings of the Parthian Empire. What he produced was a work called Parthian Stations. It is essentially a description of the Silk Road and the militarised trading stations (which might double as defensive garrisons) placed along it by Parthia. Those trading stations protected caravan-traders from bandits and beasts, and provided secure marketplaces in which to trade and retail their wares along their way. This shows how important the Silk Road was to not only the Parthian economy but also to its security, and such was Augustus’ desire to have it all for his heirs.

In the years building up to the invasion, the whole population of the Roman Empire was required to register an oath of allegiance to Augustus, his rule—and his family. This was probably the empire-wide registration described in the biblical Gospel of Luke as taking place at the time of the birth of Jesus Christ, and delineates common era (CE) with what came before (BCE). The previous registration had taken place when Rome’s western provinces swore allegiance to Augustus just prior to the Battle of Actium in which he defeated Marc Antony and Cleopatra and took control of the empire for himself. It appears that Augustus was doing something similar once again, decreeing an oath of allegiance, this time from the entire empire in order to secure his rule on the home front while his two young heirs carried Rome’s legions east against Parthia.

But the adventure into Parthia came to nothing in the end, with the Parthian king Phraataces quickly coming to terms with Rome, and when both Gaius and Lucius died not long afterwards, the whole enterprise was aborted. Isidore’s intelligence was not wasted, however, as his Parthian Stations is a dossier of morsels of valuable information for historians seeking knowledge and insight into the history and economics of the Silk Road.

Realpolitik Prevails

Both East and West had much to gain from the mainte- nance of the Silk Road. According to the Shiji, a first-century b.c. Han account of Chinese history written by Sima Qian, Parthian traders invested vast amounts of silver coinage with the Chinese for commodities in addition to silk, such as exotic foods and spices. Pliny the Elder records these same products being traded in the market places of Rome by Parthian wholesalers. He also wrote that steel, leather, rhubarb (used as medicine), peaches and other fruits, and the pistachio nut were regular imports from the East via the Silk Road (Natural History 15. 44; 34. 145; 37. 128). These commodities were traded for locally produced and empire- sourced goods including gold, wine and olive oil, which in turn made their way east to Parthia for consumption or to China and India for trade.

The silks that arrived in Roman markets were considered a natural wonder and they were highly valued. Silk was brought to the Roman Empire in a raw state, not woven, its origin a fiercely guarded trade secret by the Chinese. Once the Romans bought those silks, they would be im- mediately transported to manufacturing workshops in Syria and Egypt where they were dyed and turned into fabric and fashionable clothing for wealthy Romans. In fact, silk became a status symbol in the Roman Empire. Archaeologists working at the Syrian city of Palmyra in 1933 discovered two tombs containing silks dated to between the first and third centuries AD What’s more, we now know exactly from what part of China these silks came, as they still bore the Hunan Province symbol stamp.

Control of the Silk Road as it passed through Parthian territory was the domain of Parthia’s subjects. According to the Hanshu, a Chinese history written in China during the first century AD, the Parthians “cut off” all communication between Rome and China because “they wished to carry on the trade in Chinese silks” themselves. The Parthians maintained this level of control in order to reap the profits borne of their strategic position. By keeping China and Rome separated, Parthia was able to dictate one’s prices in the other’s markets. The Parthians bought silk in China cheap and traded them in Roman Syria for enormous sums of Roman gold. While minimising direct contact between Rome and China, they nevertheless promoted the economic interests of the other—and the desire for the other’s unique wares and products. The Hanshu also states that China tried repeatedly to open trade directly with Rome, but were always unsuccessful due to Parthian intrigue and intervention. One such attempt took place in AD 97, when the Chinese Protector-General commissioned a trading official, Gan Ying, to journey to Rome to directly negotiate a trade deal. However, the overland journey was too great for Gan Ying, and when a Parthian sailor working along the Persian Gulf told Gan Ying how far away Rome still was, he gave up and turned back to home

In the other direction, the earliest recorded visit of a Roman to China was in a.d 166 by men said to be rep- resentatives of “Andun, king of Da Qin,” who is thought to be Marcus Aurelius Antonius Marcus, the emperor of Rome, or Da Qin as the Chinese called it. They brought to the Chinese royal court gifts of ivory, rhinoceros and tortoiseshell in an effort to open trade directly between Rome and China. However, the sheer distance between these two great civilisations and the practicalities of ancient trade meant that both Rome and China would continue to trade along Parthia’s Silk Route which had been purpose-built especially for long-range and large scale trade between East and West.

In their defence, Parthia didn’t gather all the accumulated wealth to themselves. In fact, many of their subject nations shared in the profits from the trade route. In return, each region along the road was expected to maintain their section. The trading stations Isidore of Charax described dotted all along it would likely not have existed but for the maintenance each local region provided. In addition to the actual road and marketplaces, they invested in other community infrastructure, reaping even greater monetary reward.

"Commodity" exchange

Commodities were not the only things “traded” along the Silk Road. Ideas, too, traversed the mountains and deserts, eventually finding their way to some most unlikely places. Historical records show that Jews and Christians used the Silk Road to transport many religious ideas. Many Jews from all over the Parthian Empire east of the Euphrates River travelled to Jerusalem for religious festivals. According to the biblical Book of Acts, “Parthians” as well as their subjects among the “Medes and Elamites” and “residents of Mesopotamia” were present at the first Jewish festival of Pentecost in Jerusalem after the death and resurrection of Jesus (Acts 2:9). In an effort to spread the message about Jesus to those people, early Christian tradition recorded by the fourth century Church historian Eusebius records that Jesus’ own disciple Thomas was chosen by the other disciples to travel to Parthia and preach the Gospel there, which he did, before going on to India. (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History, 3. 1) No doubt, Thomas used the Silk Road to go east as Jews beyond the Euphrates used it to go west to Jerusalem.

Archaeology also supports these records that religious ideas traversed much distance along the Silk Road. Dura- Europos, the “Pompeii of the Desert,” was a Parthian town of some 5000 inhabitants at its peak. It was located on the mid-Euphrates leg of the road, and was a true melting-pot of ideas. Religious buildings preserved there contain an eclectic blend of Roman, Greek and Parthian symbols, and Greek gods were worshipped there alongside Semitic ones. The Parthians were happy with this arrangement, content to simply rule through existing local Greek and Semitic institutions, allowing local politicians to conduct their own affairs so long as they matched Parthia’s policies as well.

To the west of Dura-Europos was cosmopolitan Palmyra, a Roman city where traders from the East first entered empire territory. There, archaeologists have examined temples that depict Palmyrene gods wearing Roman breast- plates and Parthian trousers and shoes, and a temple to the city of Rome in which the Semitic god Bel was also worshiped. Places like Dura-Europos and Palmyra tell us that human movement across frontiers was simply the norm in ancient times.

Palmyra, its ancient monuments now under direct threat of destruction by ISIS, had the hallmarks of being the hub of the surrounding nations. According to Josephus, Palmyra was actually founded by King Solomon in the tenth century b.c., who saw that its natural fresh-water springs in the middle of the Syrian desert made its location a strategic one, an oasis to which people from afar would by necessity visit (Jewish Antiquities, 8. 6. 1). Whether or not Josephus was correct, it is nevertheless true that by the first century b.c. its economy was booming as a favourite stop-over for travellers.

However, it was the trade in goods that made Palmyra’s fortune. To date, some 180 ancient honorific inscriptions have been discovered by archaeologists at Palmyra, 30 of which—one sixth—commemorate exploits of various merchants hailing from there who were active along the Silk Road and other trading routes. Of these, 17 commemorate trade ventures with Charax, nine with Vologasias (a major Parthian city on the Euphrates), one each with Seleucia and Babylon, which were both situated near Vologasias, and two with India. From these inscriptions, we learn much about a number of Palmyrene traders, the most active being Soades, son of Boliades. One inscription regarding this man, dated to the year AD 132, honours him for risking his own life to protect caravan traders on their way to Palmyra from Vologasias along the Euphrates leg of the Silk Road (PAT 0197). Another (JSS S4), from AD 144, honours him yet again for similar exploits in that year. This was no fleeting fame. In fact, such was the importance of this man’s exploits that news of him reached the ears of the emperors in Rome. One inscription from Palmyra, dated to AD 145, even states that Soades was awarded commendations for bravery by both the emperor Hadrian and later on his successor Antoninus Pius. The Parthians honoured him too; the same inscription states that decrees and statues were made in his honour in both Vologasias and Characene (PAT 1062).

As the economies of the regional hubs thrived, they took on political importance, with Palmyra being the best example. Its economy was so important to the region that Palmyrene individuals became noteworthy personalities. One inscription at Palmyra, dated to AD 131, for instance, names one Palmyrene, Iarhai Nebouzabados, as Parthia’s satrap of Thilouana in modern Bahrain (PAT 1374); another mentions one Lariboles, son of Lisamsos, as acting as ambassador for Charax in the court of Orodes, king of Elymais (PAT 1414). Archaeologists working around the Persian Gulf have even found a Palmyrene tomb on Kharg Island. Astonishingly, such were the Palmyrene’s commercial and political importance throughout the Parthian Empire that in AD 142 the Parthians allowed the building of a temple honouring Rome’s emperors in Vologasias to meet local demand.

Decline

The golden age of trade along the Silk Road continued until the early third century AD A few wars between Rome and Parthia interrupted the trade for a time but generally trade was allowed to thrive. However, the power of the once mighty Parthian empire declined until it finally fell to the Sassanid Persians. Trade along the silk route continued until well into the second millennium, when sea routes became better developed.

The Sassanids were a new kind of threat to international trade and they virtually throttled trade on the traditional Rome–China terrestrial routes. And with the Roman world wracked by civil war for almost a century more, an inevitable decline in trade resulted. The Palmyrenes attempted to save their situation and in the AD 270s, led by their charismatic queen, Zenobia, they managed to carve out an empire of their own and to reinvigorate the economies of the Near East. But it was all to no avail. Rome came down hard on Zenobia and Palmyra, and the Sassanid Persian Empire remained closed to trade with Rome.

And while Rome would still trade with India via a southern route from its ports on the Red Sea, and the Venetians and others from later times kept the northern land routes operational, the place and importance of the Silk Road declined not to be seen again until contemporary times, when massive container ships with cargoes of tens of thousands of tonnes began to ply their way from Chinese ports such as Guanzhou to ports of Europe linking East and West as the Silk Road had done in the ancient world.