Archibald Sayce is recognised as a giant among archaeologists; he succeeded in just about everything he set his mind to. But his life didn’t begin that way. Born on September 25, 1845, in the small town of Shirehampton, Bristol, on England’s west coast, he almost never made to adulthood. While still a child, the young Archibald developed tuberculosis, which nearly killed him. But his close shave with death energised him for the rest of his life, and he determined to make every moment count. He applied himself to his schooling, so much so that by the age of 10 he was reading Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey—in Greek! Sayce’s love of the ancient world, which began with Homer, continued the rest of his life and in 1869 he became a research fellow at the Queen’s College at Oxford University.

Mesopotamia

In the 1870s, Sayce’s interest in ancient history and archaeology shifted focus further east to the Ancient Near East, especially Babylonia. Soon he began studying the astronomical and astrological methods used by the Babylonians in ancient times through their ancient form of writing called cuneiform. In this, Sayce was breaking fresh ground and by 1874 he was one of only a handful of people who could read the Babylonian text and astrological tables.

The vast ruins of Hattusa, the capital of the Hittites, with a reconstructed section of the wall in the background. Sayce and Wright identified these ancient ruins at Boghazkoy as Hattusa.

The vast ruins of Hattusa, the capital of the Hittites, with a reconstructed section of the wall in the background. Sayce and Wright identified these ancient ruins at Boghazkoy as Hattusa.

The Hitties

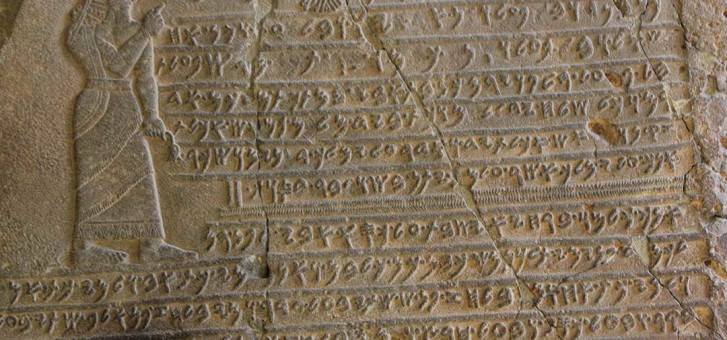

But in the late 1870s, his attention had shifted to Syria and Anatolia in present-day Turkey. There, Sayce began to compare various carved reliefs and hieroglyph-like pictorial inscriptions across the Turkish plateau, and in doing so made an astounding breakthrough: he had discovered the evidence for the long-lost Hittite Empire. To that point, the Hittites were known only through a few brief references made about them in the ancient Hebrew the Pentateuch—first five books of the Hebrew Bible. Nobody knew anything about them until Sayce’s revelations.

Together with archaeologist William Wright, Sayce identified ancient ruins near Boğazkale as Hattusa, the legendary Hittite capital, and through fieldwork they found that the Hittite kings of Hattusa had once ruled a vast empire stretching from the Aegean Sea to the Euphrates. At around the same time as this, many Egyptian records from an ancient archive were surfacing in Egypt, some of which referred to a Hittite empire. These, together with Sayce’s findings, introduced the world to the Hittite empire.

But Sayce was not one to rest. He was very soon decoding the hieroglyph-like pictorial writings of the Hittites. He had deduced that each symbol stood for a phonetic sound. And as there were so many of such pictographs, Sayce concluded that the Hittites apparently had a very complex language with far more types of syllables than a mere alphabet could handle. There were simply too many sounds in the Hittite language for a manageable alphabet. So they used many pictures instead.

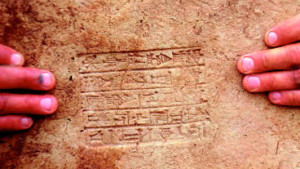

A lunar eclipse omen tablet in the British Museum. Sayce studied the astronomical and astrological methods used by the ancient Babylonians.

A lunar eclipse omen tablet in the British Museum. Sayce studied the astronomical and astrological methods used by the ancient Babylonians.

Breakthrough

Sayce’s dream was to find a “Rosetta Stone” of the Hittites, to unscramble the Hittite language. And in 1880 he found something akin to it. In Istanbul, a very ancient silver disc had come to light, which contained a hieroglyph of a warrior surrounded by cuneiform words in the Hurrian dialect. Sayce, utilised his knowledge of cuneiform and the Hittites and concluded that the warrior portrayed was a Hittite symbol and that the cuneiform words around it expressed the same meaning as that symbol. However, it would take many more years for the world to learn the language of the Hittites. By 1886, just seven Hittite writing symbols had been decoded. Although it was very little in the vast array of symbols, it was nevertheless a significant beginning.

Temple of Rameses II, at Abu Simbel, Egypt. In the right foreground is a stele depicting the marriage between Rameses and the Hittite princess Naptera, which ratified the treaty of Kadesh. Such references to the Hittites in ancient Egypt led Sayce to turn his attention to Egypt.

Temple of Rameses II, at Abu Simbel, Egypt. In the right foreground is a stele depicting the marriage between Rameses and the Hittite princess Naptera, which ratified the treaty of Kadesh. Such references to the Hittites in ancient Egypt led Sayce to turn his attention to Egypt.

Egypt

While working in Hattusa, Sayce came across a Hittite archive of diplomatic records, many of which contained references to Egypt. By comparing this archive with that recently found in Egypt (which in turn referred to the Hittites), Sayce was able to piece together an account of the robust to and fro of the political times between the two great empires. His interest whetted, he turned his hand to Egyptian archaeology and by the early 1900s was conducting fieldwork at El Kab in Egypt.

Sayce was the authority on the Hittites and the ancient Near East of his day. As Professor of Assyriology at Oxford University (1891–1919), his knowledge of the ancient world and archaeology of the region was staggering. However, as great as he was, Sayce was also a devout Christian, with biblical teachings and history giving his work a context and a perspective to his life. For example, when asked his thoughts on life in the ancient world Sayce would say, “The community in which each man acts like his neighbour is not yet a civilised community.” This was as much an observation about his own world of early twentieth century Europe, which saw the human carnage of the Great War and the beginnings of fascism as it was about the ancient world in which he was immersed.

Sayce died on February 4, 1933, a recognised authority across numerous fields of archaeology and history. But he is best remembered as the discoverer of the mighty empire of the Hittites, which confirmed his view of biblical history as correct and reliable.