In a cemetery dedicated to Egyptian pharoahs located in Abydos, in the south at Upper Egypt, the archaeologist Arthur Petrie and his team were working to uncover the burial sites of Egypt’s ruling first dynasty. The year was 1900. A tomb stela naming Meryt-Neith (also translated as Meritnit or Merneith) had been uncovered. It was seen as a ruler’s funerary stela despite not carrying the royal Horus name associated with rulers as was traditionally used, as the tomb was large—on the same scale as other burials at the site—and enhanced by an impressive 40 auxiliary graves for associated servants. The evidence revealed one Meryt-Neith as a ruler of the First Dynasty, very likely the third person to be so. The grave as prepared showed that the one to be buried there was of great significance.

This Meryt-Neith also had recognised status in Lower Egypt, in Sakkara in the north, with a funerary monument that included a solar boat. This was a very meaningful inclusion as the symbolic transport for the deceased into the afterlife. Therefore two burials were prepared for Meryt-Neith, one an actual tomb and the other as a monument, a symbolism customary for the early rulers of ancient Egypt.

However, only later when the name was studied further was it revealed that the name was that of a female, translating as “beloved of the god- dess Neith.” From this, applying the contemporary beliefs and cultural attitudes of the day, Meryt-Neith was downgraded from pharaoh to queen- consort. But not all academics agreed with this, considering that the twin tombs and solar boat were privileges reserved for those of only the highest status—pharaoh.

So who then was this Meryt-Neith from the very earliest Egyptian history? To find out, we journey back to the dawn of Egyptian dynasties, the very first one in fact; the Early Dynastic Period (ca. 3050–2613 b.c.).

Meryt-Neith is linked with the ruler Djer, possibly as his daughter, married to the ruler Djet and was the mother of their child, Den. Seals in her tomb at Abydos bear the name of Den, who was an infant at the time of his father’s death. It is thus quite likely that Meryt-Neith was a co-ruler or regent on behalf of her young son. Den eventually went on to rule for a long period; he would have had the authority to lay his mother to rest along with other former rulers at Abydos.

Meryt-Neith’s name is among the rulers listed on The Palermo Stone (one of the so called “kings lists,” which dates to Dynasty Five, a record of all previous rulers of Egypt), noting her as a pharaoh’s mother but not as a pharaoh outright. However, to give that some context, kings’ lists do not acknowledge every known pharaoh. The Abydos list, for example, which dates to the much later Nineteenth Dynasty of the New Kingdom and created during the reign of Seti I, fails to mention certain undisputed rulers of their day, namely the female Hatshepsut, and Akhenaten and Tutankhamen.

It was during Dynasty Six of the Old Kingdom that after some 90 years, the rule of Pepi II ended. (The length of ruling years is disputed, with some academics suggesting less, possibly 60 or so years—an amazingly long rule at any rating.) This resulted in instability, as Pepi II had outlived his sons and there was no obvious direct successor. So who succeeded him?

The “Turin Canon” (or Turin Papyrus), another kings list, acknowledges the queen Nitokerti (or Nitocris) from the Old Kingdom as ruling for two years following Merenre’s kingship, after Pepi II. But who was Nitocris?

It seems she was real enough, despite no actual ar- chaeological record of her existence uncovered to date. All references to her derive from much later times. The Egyptian historian Manetho, a priest from Sebennytos who lived during the Ptolemaic era of approximately third century b.c., praised her as being “of fair complexion and the most bravest and beautiful woman of her time.” Herodotus tells a story that places Nitocris as ruler of Egypt after the murder of her brother Merenre II, who set about to destroy those responsible by drowning them during a banquet held underground, which she then flooded with the waters of the Nile. Further, many scholars believe that the spelling of the name is an incorrectly noted male ruler’s name.

In the Middle Kingdom, the final ruler of the Twelfth Dynasty was Queen Sobekneferu (c. 1777–1773 b.c.), the daughter of the ruler Amenemhat III. Although her tomb is yet to be discovered, she is precisely listed in the Turin Canon as ruling for three years, 10 months and 24 days. It was upon the death of her husband (possibly her brother) Amenemhat IV that Sobekneferu took the helm of ruling the Two Lands and a number of evidences of this survive, yielding more information. Sobekneferu was not a regent ruling on behalf of her baby son but a ruler in her own right. She had five royal names, four of them listed on a glazed steatite seal today housed in the British Museum. Despite its small size—just 4.42 cm (1.7 in) in length and a diameter of 1.55 cm (0.6 in)—the importance of the seal is immense. The titulary records her Horus name as “Beloved of Re,” inside a serekh with a falcon image carved atop it. The name “Sobekneferu” utilises the name Sobek (the crocodile-headed god of the Faiyum), an inclusion that stresses the link between the ruler and the god. Another link to her reign is recorded at the Nubian fortress of Kumma, in a notation recording the inundation level of the Nile in her third year as ruler as 1.83 metres (6 ft).

An intriguing red quartzite, headless statue of Sobekneferu in the Louvre Museum displays the unique combination of both female and male attire, a strong statement of a woman ruling the Two Lands in the role of a traditional pharaoh. Although the queen wears the shift-style dress of a woman, a further item of male attire, a kilt, is worn over this, a knife at the waist secured by a belt. The long lappets of a nemes head cloth are also carved over the shoulders, depicting yet another traditional icon of a male ruler.

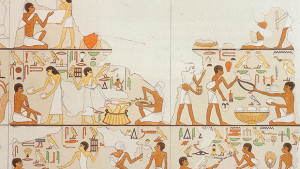

During the Eighteenth Dynasty of the New Kingdom, the queen and Great Royal Wife Ahmose Nefertari acted as regent for her infant son Amenhotep I (c. 1551 b.c.) when her husband, the ruler Ahmose, died. She again took up the role when the wife of Amenhotep I also died, and assisted in determining who would be the successor. In the town of Deir el-Medina, both mother and son had a posthumous cult following their deaths until the end of the New Kingdom (c. 1070 b.c.). In this capacity, Ahmose-Nefertari was elevated to that of goddess and referred to as “Lady of the West” and “Mistress of the Sky.” In a depiction of Ahmose-Nefertari from a Theban tomb wall fragment, her skin is painted black in reference to the fertile land of Egypt, known as kemet, or Black Land.

In the Nineteenth Dynasty of the New Kingdom came a queen who ruled Egypt. Tawosret ruled on behalf of her stepson until his death at the young age of 20. Sometimes identified as Twosret (c. 1187–1185 b.c.), she was the wife of Seti II, whose sickly son Merenptah-Siptah (later Siptah) had attained the role of ruler but required a

regent. Tawosret’s story is one of determination through many obstacles. She was not the mother of Siptah and not a so-called “King’s Daughter” (which would have automatically elevated her status). She endured a power struggle with the “Great Chancellor of the Whole Land,” called Bay, and maintained her status despite the chaos that resulted from the death of Siptah. Despite this, she became ruler in her own right, adding the years served with her stepson to her own independent rule with the highest verified evidence of year 8. Although she was to rule independently for only two years, she was nevertheless afforded a tomb in the Valley of the Kings, quite an achievement, as the only other female and ruler to have achieved this being Hatshepsut some 250 years before. And if you are visiting, her tomb is known as KV14. It is decorated with a painted ceiling that features astronomical scenes from the “Book Of Caverns.” However the ruler Sethnakhte usurped this tomb in the Twentieth Dynasty and her sarcophagus was also re-used! Although her burial trove had been looted, some scholars believe her mummy to be that identified as “Unknown Woman D,” discovered in the tomb of Amenhotep II, and now housed in the Cairo museum.

The surviving evidence for female rulers varies greatly in content, volume and context. From the stupendous mortuary temple of Hatshepsut in the Valley of the Queens and her magnificent obelisk of 29.5m (97 ft) at Karnak, the many tombs, statues and wall paintings to the small glazed cylinder seal of Sobekneferu measuring just over 4 cm (1.6 in), or perhaps just as a notation on a king’s list, there is much to be considered and learned. Either on behalf of their husbands, sons, stepsons or independently, the women who ruled the Two Lands did so as queen or pharaoh.

References:

- Calendar, G. (2003) The Middle Kingdom Renaissance in. The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, ed. Shaw, I. Oxford University Press: Oxford.

- Cotterell, L. (1967) Lady of the Two Lands, The Bobs-Merrill Company: United States of America.

- Newberry, P.E (1943) Queen Nitocris of the Sixth Dynasty. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, v.29, pp. 51-54.

- Tyldesley, J. (1995), Daughters of Isis, Penguin: England.

- Tyldesley, J. (2006), Chronicle of the Queens of Ancient Egypt, Thames and Hudson: London.

- Watterson, B. (1991), Women in Ancient Egypt, The Bath Press, Bath. p://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/aes/g/glazed_steatite_cylinder_seal.aspx

- Link to glazed steatite cylinder seal of Sobekneferu accessed 29 May 2015.