Ur of the Chaldees is only mentioned five times in the Bible, and they all refer to the same incident. “And Terah took his son Abram and his grandson Lot, the son of Haran, and his daughterin-law Sarai, his son Abram’s wife, and they went out with them from Ur of the Chaldeans to go to the land of Canaan” (Genesis 11:32).

For a long time it was not known where Ur was or whether it even existed, but in 1864 J E Taylor, the British consul in Basra, was asked by the British Museum to try to find some antiquities for the museum. Henry Layard had earlier excavated at Nineveh and had sent back shiploads of winged bulls and statues to the museum, and the British public was hungry for more.

aylor knew of a ruined city 300 kilometres north of Basra called Tell el Maqayya, meaning “Mound of pitch.” It was so named because of the remains of a large ziggurat, made of bricks stuck together with bitumen, which stood there.

Taylor was not an archaeologist and assumed that the ziggurat was hollow and may contain the treasures the museum needed, so he set his labourers to work on top of the ziggurat, hoping to break through into the room below.

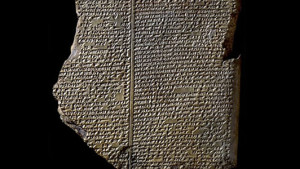

There was no room below, and after removing a huge number of bricks Taylor gave up. All he could send back to the museum were some cylinders inscribed with cuneiform writing which no one could read at that time. The cylinders remained in the back room of the museum until Sir Henry Rawlinson deciphered the cuneiform.

When the cylinders were translated authorities were astonished to learn that the cylinders told of renovations that had been done on the ziggurat by a king whose name was Ur Nummu. Could it be that this king’s name was Nummu; and he was king of Ur of the Chaldees? Indeed it was, and so it was realized that the biblical Ur was not some small village but an important metropolis of some ancient civilization.

In 1922 a joint expedition by the British Museum and the University of Pennsylvania Museum, under the direction of Leonard Woolley who excavated there from 1922 to 1934, began. He made some spectacular discoveries, including sixteen royal tombs which yielded some fabulous treasures.

In front of these tombs he discovered areas which he described as the “death pits of Ur.” He concluded that when a king was buried, anything up to 80 of his royal staff were buried with him. Woolley found a bowl which he thought would have contained poison, and many cups from which the servants could have drunk the poison. He reasoned that they would then lay down and die, and the whole pit would then have been filled in and the bodies buried. He vividly describes it in his book Excavations at Ur:

"The royal body was carried down the sloping passage and laid in the tomb chamber ... When the door had been blocked with stone and brick and smoothly plastered over, the first phase of the burial ceremony was complete. The second phase, as best illustrated by the tombs of Shub-ad and her husband, was more dramatic.

Down into the open pit, with its mat-covered floor and mat-lined walls, empty and unfurnished, there comes a procession of people, the members of the dead ruler's court, soldiers, men-servants and women, the latter in all their finery of brightly-coloured garments and headdresses of carnelian and lapis lazuli, silver and gold, officers with the insignia of their rank, musicians bearing harps or lyres, and then, driven or backed down the slope, the chariots drawn by oxen or by asses, the drivers in the cars, the grooms holding the heads of the draught animals, and all take up their allotted places at the bottom of the shaft and finally a guard of soldiers forms up at the entrance. Each man and woman brought a little cup of clay or stone or metal, the only equipment needed for the rite that was to follow.

There would seem to have been some kind of service down there, at least it is certain that the musicians played up to the last; then each of them drank from their cups a potion which they had brought with them or found prepared for them on the spot - in one case we found in the middle of the pit a great copper pot into which they could have dipped - and they lay down and composed themselves for death ... and when that was done, earth was flung in from above over the unconscious victims, and the filling-in of the grave shaft begun ...”

All very dramatic and interesting, but now this concept has been challenged. Recently archaeologists at the Pennsylvania University conducted CT scans on two of the crushed skulls. The computer generated picture which resulted conveyed to them the idea that the skulls had been hit with a round

instrument about 25 millimetres in diameter which penetrated the skull and caused instant death. They therefore concluded that the victims had not died from poison as Woolley had originally surmised.

This is very impressive and they may be right, but it would not be wise to jump to early conclusions. In the first place, only two skulls were examined. That does not prove that the other 598 were treated in the same manner

Can they be sure that both did not happen? Could it be possible that the victims did drink from their poison cups and lay down to die, and then while unconscious, perhaps these blows were struck to ensure death. That would be preferable to the victims waking up and finding tons of earth being heaped up over them.

Whichever it was, the death pits of Ur provide us with an insight into ancient practices. Of course they were

not the only ones to care for their kings in the afterlife in this manner. There is evidence that the kings of dynasties 1 and 2 in Egypt were accompanied by their servants into future life.

The Pennsylvania report raises the question of the psychology behind these practices. Why would anyone sign up for palace service if they knew what lay ahead? To Western thinking this would seem very undesirable, but these servants would have the prospect of a permanent job in a very desirable environment with all the luxuries of life which few of their contemporise could hope for.

There was also the prospect of being immediately ushered into a similarly luxurious environment in the life to come. Kings were mummified and their bodies buried in elaborate tombs. This, in their thinking, guaranteed them a pleasant existence in the future life. Servants could not hope for such expensive treatment for their bodies after death. This was a short cut to heaven which would compensate them for the prospect of death should their king die before they did.

So it was not a good idea from our perspective, but one that could have appealed to those who had a strong belief in the life to come.