Sumer was the ancient civilization that existed in southern Iraq from earliest historical times for about 1500 years.

The Sumerians were a brilliant people who first invented writing, the wheel and the arch. Sir Leonard Woolley’s excavations at Ur of the Chaldees, capital of the Sumerian Empire, from 1922 to 1934 revealed an advanced civilization in which schoolboys could work out “multiplication, reciprocals, coefficients, balancing of accounts, how to make all kinds of pay allotments, divide property and delimit shares of fields” (page 23). For that they had to be able to work out the area of a triangle, use the formula 2piR, as well as calculate square and cube roots.

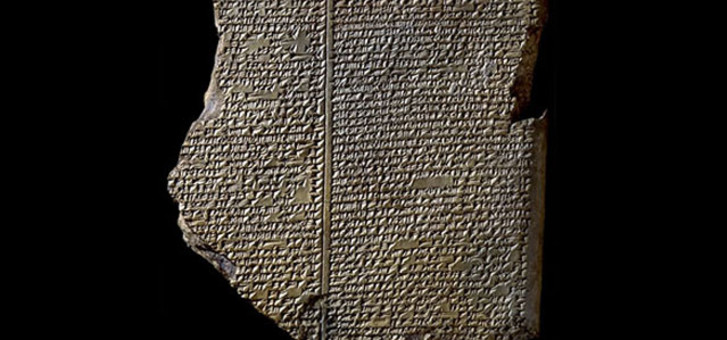

The Sumerians left a vast volume of literature in the form of clay tablets. Clark claims that “there are more cuneiform tablets extant today than medieval manuscripts, though the tablets are nearly ten times older. Of the

thousands of tablets recovered, just one per cent have been read, notes Leichty, and there are millions more to be unearthed” (page 24).

Just one city, Nippur, yielded enough tablets to keep scholars going for a century. “Much of the University of Pennsylvania’s tablet collection comes from its work in Mesoptamia, starting with a dig in 1889—the first expedition to the region by an American institution. After a rocky start, and the death of one team member, expedition leader Hermann Hilprecht hit pay dirt. The initial site selected proved to be Nippur—a holy city of the Sumerians and Akkadians. By 1900 Hilprecht had excavated some 60,000 tablets found in the city’s library. The tablets included school lessons, multiplication tables, king lists, astronomical records, legal documents, hymns and epic tales” (page 23).

Who were the Sumerians?

The amazing thing is that with all this literature available we still do not know who the Sumerians were, where they came from or how they got there. Their language bears little resemblance to anyone else’s and it is astonishing that they had so many scribes who were able to read and write it. Many school children in our society today find it difficult to cope with an alphabet of only 26 letters. Pity the students back there who had to cope with hundreds of cuneiform signs.

“Sumerian is a very difficult and obtuse language, says Tinney. It has no relatives—living or dead. The script is not syllabic, let alone alphabetic—it’s logographic, like Chinese. The language consists of a repetition of signs, 600 common ones and 2000 or so if you add the obscure ones. Handwritings differed and sign values changed over time, and a given sign might have eight or nine different meanings. There is no punctuation and no space between the words... The origins of the Sumerians themselves are purely hypothetical” (page 24).

Needless to say, the production of a dictionary of their language is a time consuming undertaking. It will take four volumes to deal with the letter A, the fourth one is expected to come off the press next year. “An initial version of the dictionary should be done within five to ten years Tinney estimates, and then the team will go on to publish a completely exhaustive treatment.” That may not be in our lifetime, and by then perhaps, archaeological work will be able to resume in Iraq, and thousands of more tablets may turn up, and the dictionary will have to be revised.

Creation and Flood Tablets

Among the tablets that have been found are those that deal with myths and religion. These include the story of creation and the flood. Naturally they differ in detail from the creation story in Genesis 1-3 and the story of Noah and the flood in Genesis 6-9 in the Bible, but the concepts are the same. This has led some scholars to conclude that the Bible writer copied the Mesopotamian stories while others claim that the cuneiform scribes copied the Hebrew story. Still others point out that, as similar legends exist in many other nations around the world, it indicates that they all have a common origin in historical fact.

Clark says, “The tablet resting in my hand dates to around 1800 BC and provides one of the earliest known accounts of the Garden of Eden. Sjoberg reads from it, describing Dilmun, a land firmly identified as today’s Bahrain, just off the coast of Saudi Arabia—where ‘the lion makes no kill, the wolf snatches no lamb’ and where no one grows old. Then Enki, the god of the abyss, or Abzu in Sumerian, nibbles forbidden plants from the garden of the earth-goddess Ninhusarga and is severely punished for his deed.”

By way of comparison, Genesis says, “To every beast of the earth... I have given every green herb for food” (Genesis1:29). “Because you have heeded the voice of your wife, and have eaten from the tree of which I commanded you saying, you shall not eat of it, cursed is the ground for your sake,... for out of it you were taken; for dust you are and to dust you shall return” (Genesis 3:17-19).

“The tale of Enki and Ninhursaga, of course, is similar to the Paradise stories in the Bible and the Quran. The stories of creation and the great flood also have precedents in Sumerian literature. The flood story, for example, figures in the tale of Gilgamesh, a hero who sets off on a journey to find life everlasting. After travelling to Dilmun to meet Ziusudra, the survivor of the flood, he gains immortality in the shape of a flowering plant” (page 23).

“I’d love to talk to the Sumerians,” Leichty says. “They were a highly sophisticated society, and I’d like to understand them a bit better” (page 25). He and many others—scholars and laymen alike—may have that chance, as the rest of the Pennsylvania Sumerian Dictionary gets ready to roll off the presses and down the information superhighway.