Now suppose you came to a country where you could fill a theatre by simply bringing a covered plate onto the stage and then slowly lifting the cover so as to let everyone see, just before the lights went out, that it contained a mutton chop or a bit of bacon, would you not think that in that country something had gone wrong with the appetite for food?”

C S Lewis imagined this fanciful food burlesque in his book Mere Christianity to illustrate the twisted sexual desires of the modern age. What Lewis couldn’t possibly have known was that his absurd example would actually be lived out a half-century later, not metaphorically over sexual perversion, but literally with food.

Food has become a celebrated enjoyment, a sort of erotica of taste and indulgence. Turn on your TV and you’ll be slapped in the face with advertisements featuring gorgeous, sizzling meals. Cooking programs where chefs use the most esoteric and expensive ingredients to craft mouth-watering dishes are wildly popular. Chefs compete for prizes and for our entertainment, and they curse one another about how to run a restaurant kitchen. Books about gourmet food have never been more popular. In any restaurant you might see a whole table of people whipping out their phones when the server arrives so they can capture photographs of their plates and share them on social networks.

The obsession with food in wealthy countries runs the gamut from the exotic to the simple. An example of the exotic is the foods prepared by British chef Heston Blumenthal. Swedish chef Magnus Nilsson makes thousand-dollar “tasting experiences” from the freshest and rarest natural ingredients, some of them harvested on his own northern Scandinavian farm. Then there’s artificial food. Most fast-food items owe more to laboratories than farms and French chef Hervé This crafts gourmet meals entirely from chemicals!

The Bible and gluttony

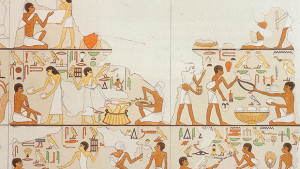

We think of gluttony as eating to excess, but the Bible’s picture of gluttony is more nuanced. The children of Israel had already had enough to eat when they demanded that God provide them with a better menu: “If only we had meat to eat!” they complained. “We remember the fish we ate in Egypt at no cost—also the cucumbers, melons, leeks, onions and garlic” (Numbers 11:4, 5).

Esau created a family rivalry between the Edomites (Esau’s descendants) and the Israelites (descendants of his brother, Jacob) that lasted for hundreds of years when his appetite caused him to trade his birthright for a bowl of stew (Genesis 25:30–33). One interpretation of the story of the high priest Eli’s wicked sons suggests that their sin was not just taking the best of the sacrificed meat but preparing it in ways to stimulate the palate (1 Samuel 2:12–16).

Medieval scholar Thomas Aquinas wrote that “gluttony denotes inordinate concupiscence [lust] in eating”—which may be why some people refer to the current obsession with food as “food porn.”

While gluttony is a sin, the Bible doesn’t condemn eating or the enjoyment of it. When Jesus received food, He gave thanks to show that it was a gift from God. Jesus’ enemies contrasted John the Baptist’s desert asceticism with Jesus’ active social life, calling Him a glutton and a drunkard (Luke 7:33, 34). But banqueting with the rich was relatively rare in Jesus’ life, though on one occasion he dined with a wealthy tax collector whom the religious leaders of the day hated (Luke 19:1–10). Sometimes Jesus and His disciples were reduced to munching on kernels of grain they plucked in the fields (Matthew 12:1). Only five consumables are specifically identified on Jesus’ menu: fish, water, lamb, bread and grape juice. In two famous miracles, He actually created baked bread and cooked fish to feed to the hungry crowds. And on the occasion of His last Passover meal with His disciples, He ate three of the five: the lamb, the bread and the grape juice.

Psychologist Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs, which he illustrated with a pyramid, placed our physical needs at the bottom as the foundation for all the others. After all, who can sustain life without food, air, water and protection from the elements? Beyond these are aspirations for safety, belonging, self-esteem and at the pinnacle of the pyramid Maslow placed the spiritual component, which he called self-actualisation.

Contrast that with Jesus’ hierarchy of needs. He asked, “What good is it for a man to gain the whole world, yet forfeit his soul?” (Mark 8:36). Jesus didn’t insist on severe physical denial as a way to enhance our spiritual nature. But He was abundantly clear that, from an eternal perspective, a right relationship with God takes priority over food, clothing and shelter. He said, “Seek first his kingdom and his righteousness, and all these things will be given to you as well” (Matthew 6:33).

Because our physical appetites address fulfilment at the most fundamental level of human existence, Jesus used them as metaphors to inspire our spiritual appetites. Jesus warned His disciples, “Do not work for food that spoils, but for food that endures to eternal life.” And He added, “I am the bread of life. He who comes to me will never go hungry, and he who believes in me will never be thirsty” (John 6:27, 35).

The Lord’s Supper

In the spring of each year the Jewish people celebrate the Passover supper, a meal filled with remembrances of how God had rescued them from slavery in Egypt. Jesus also celebrated the Passover, but at His last Passover meal He added a new metaphor. Breaking a loaf of unleavened bread, He passed it to His disciples and said, “Take and eat; this is my body.” Following this He passed a cup of grape juice among them and said, “Drink from it, all of you. This is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins” (Matthew 26:26–28). By concluding with the words “do this in remembrance of me” (Luke 22:19), Jesus established the Lord’s Supper as a ritual of remembrance that Christians continue to observe.

It isn’t necessary to get into a pedantic theological argument about whether the bread and grape juice are a means of grace or a symbol of grace (a debate between Catholics and most Protestants). I’m inclined to agree with C S Lewis, who said, “Do not think that I am setting up baptism and belief and the Holy Communion as things that will do instead of your own attempts to copy Christ.”

What is clear is that in the Lord’s Supper Jesus invites us to invert our instinctual human hierarchy of needs. Bread and grape juice don’t only point to higher spiritual realities. They also point to a willingness to give up life itself for the sake of eternal things. Thousands of Christian martyrs have already given testimony to the possibility of human beings living within and dying for these radically reordered priorities. And in the Lord’s Supper, we too affirm that “life is more than food, and the body more than clothes” (Luke 12:23).

Our modern food obsession (and, indeed, the indulgence of all our human appetites) can only appear at its cheapest and most tawdry in light of the Lord’s Supper. For it is there that Jesus asks us to remind ourselves, again and again, that there’s far more to life than the elements that keep us alive.