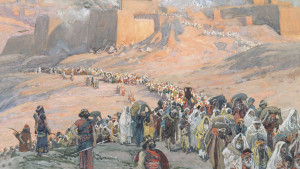

After the fall of Assyria and the rise of the Neo-Babylonian Empire in the late seventh century BD, Babylonia subjugated many smaller kingdoms, including the kingdom of Judah. Then, as retribution for an initial rebellion against their new Babylonian overlords, much of the population of Judah was taken into captivity to Babylon. Across three waves, both prominent and common citizens of Judah were exiled to Babylon and its surrounding area and were held there until the Persians conquered Babylon, who repatriated the various subjugated nations to their homelands. From archaeological excavations, it is clear that the land of Judah, the Jewish homeland, remained destitute during the Babylonian period, occupied sparsely by a primarily rural population.

The story of the biblical character Daniel begins by describing his capture along with others in the third year of King Jehoiakim of Judah (see Daniel 1:1–6), ca. 605 BC Rulers mentioned in the narrative include King Nebuchadnezzar II, Belshazzar the co-regent of Babylon, Cyrus the Great and King Darius I, all of whom are attested in inscriptions and monuments from their reigns.

When Daniel arrived in Babylon during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II, the city was probably the largest in the world, with a population estimated at approximately 200,000 people. The city may have encompassed nearly 900 hectares along both sides of the Euphrates River. Babylon was defended by an inner and outer wall, plus moat. Additionally, another defensive wall north of the city extended between the Tigris and Euphrates. With a powerful army and defences such as these, the capital appeared impregnable.

The city name itself—“Babylon”—is a Greek rendering of an ancient name, which is debated by scholars. Some argue it represents the Akkadian Babili, meaning “gate of god,” while others argue it derives from an earlier, unknown language. The most famous “gate” of Babylon, the Ishtar Gate, was constructed during the life of Daniel and remained partially intact for thousands of years.

However, the iconic Hanging Gardens of Babylon, one of the ancient Wonders of the World according to late sources, were not present while Daniel resided in Babylon—or indeed any other time in the history of the city.

While later writers such as Diodorus Siculus of the first century BC referenced Ctesias as his source when discussing the hanging gardens, and Josephus of the first century AD attributed the gardens to Nebuchadnezzar with Berossus as his source, earlier historians such as Herodotus and Xenophon make no mention of the gardens now so famous in traditional lore. Reference to the hanging gardens or any type of waterworks that would irrigate the gardens is also missing from the records of Nebuchadnezzar, even though records about building projects from his reign are extensive. Archaeological excavations at Babylon have likewise failed to locate any evidence for the monumental gardens. In the records of earlier Assyrian kings, however, there are references to waterworks in Nineveh and the gardens that they irrigated according to the Banquet stele of Assurnasirpal II and the palace without a rival inscrip- tion of Sennacherib. A carved panel from the palace in Nineveh actually depicts the Assyrian king Assurbanipal surrounded by an impressive, irrigated, well-organised garden within the city. While scholars initially attempted to identify this garden with Babylon, it is now understood that the fame hanging gardens were actually in Nineveh. Interestingly, the biblical book of Daniel likewise never mentions any grand garden in Babylon.

Dating the record

Although the oldest currently known copy of the book of Daniel dates to the second century b.c, the book itself and other ancient writers state that it was composed by Daniel in Babylon during the sixth century BC The earliest existing Septuagint manuscript copy of Daniel is dated to ca. 100 b.c, and the 4QDanc scroll from Qumran is commonly dated to ca. 125 BC While these are acknowledged to be copies of earlier manuscripts, how much earlier could the book have been written? Daniel is comfortable in the service of pagan kings, and pagan kings are friendly toward Daniel and his God, but this would be an illogical setting if the book were composed in the late Hellenistic or Maccabean period of the second century BC because of the persecution by Antiochus IV and the harsh opposition to Hellenism by the independent Judeans.

Additionally, the Hebrew and Aramaic used in the book predate second century BC, indicating at least the third century BC Within the Septuagint, mistakes incorrectly rendering Persian loan words into Aramaic and Akkadian terms also show that the translators were ignorant of a distant time and place, suggesting the original was written prior to the Hellenistic period, that is, prior to the fourth century BC The linguistic influence from Akkadian prophetic literature also agrees with a date for the composition of the book of Daniel as at least as early as the fourth century BC, and Greek musical loanwords in chapter three appear to date back to the sixth century BC Further, the correct references to customs and terms used at the Persian court are evidence of the antiquity of the stories and composition of the book in the Persian period. Finally, precise historical details that indicate composition in the sixth century BC, during the period in which the events of the book are set, include names of kings and officials, years of their reigns and several specific events. From this evidence and the details that follow, one may reasonably conclude that the book of Daniel was written in the late sixth century BC

The Judean presence in the Babylon region during the life of Daniel in the sixth century BC is known not only from the Hebrew Bible, but also from cuneiform tablets of both the Babylonians and the Judean exiles themselves. Year seven of Nebuchadnezzar II in the Babylonian Chronicle states that they took the king of Judah (Jehoiachin) cap- tive to Babylon, and the Ration Tablets discovered in excavations at Babylon mention Yaukin (Jehoiachin) the king of Judah and his children receiving rations from the royal house while in captivity in Babylon, in addition to references to other unnamed Judean officials.

The Al-Yahudu Tablets, which date as early as ca. 572 BC, describe a community of Judean exiles living in a rural village near ancient Borsippa, southwest of Baghdad. The tablets are written primarily in Akkadian, with some Aramaic notation, suggesting that the Judean exiles adopted the local language and writing of the Babylonian empire. According to the story, Daniel and his friends Hananiah, Mishael and Azariah learned the writing and language of Babylon, but it seems that most of the exiles from Judah merely employed scribes to write Akkadian documents for them (see Daniel 1:4, 5, for example).

The content of the tablets is primarily economic and legal, including information about agriculture, commerce, property leases and sales, loans, military service, taxes and slavery. The practices reflect adoption of the Babylonian laws and customs. While many of the names in the tablets are Hebrew, and even contain epithets to the Jewish God, Yahweh, no mention of Israelite religious practices have been found in the texts. This agrees with the implied ideology of the Judeans who had remained in the Diaspora after Cyrus the Great allowed the exiles to return to their homelands, as reflected especially in the book of Esther.

Nebuchadnezzar II, whose name means “Nabu [god of wisdom and son of Marduk], preserve my firstborn son,” was the Babylonian king who conquered the kingdom of Judah and took many people into exile. He reigned from ca. 605–562 b.c, ascending to the throne immediately after the death of his father King Nabopolassar. Part of the Babylonian Chronicle, sometimes referred to as the Jerusalem Chronicle, briefly describes the rise of Nebu- chadnezzar, the subjugation of Judah and the surrounding regions about the time of the captivity of Daniel, and the first siege of Jerusalem culminating in the deportation of King Jehoiachin and appointment of King Zedekiah as a vassal ruler of Babylon.

Nebuchadnezzar also commissioned numerous inscrip- tions and construction projects, many of which have been recovered through archaeological investigation. The book of Daniel describes Nebuchadnezzar as having done much building in Babylon during his reign, and specifically mentions his palace.

All this happened to King Nebuchadnezzar. Twelve months later, according to the biblical narrative (Daniel 4:28–30), he was walking upon the royal palace of Babylon surveying his accomplishments and power. The king reflected and said, “Is this not Babylon the great, which I myself have built as a royal residence by the might of my power and for the glory of my majesty?”

An inscribed brick recovered from Babylon records the building of a royal palace in Babylon by Nebuchadnezzar II, confirming one of the specific building projects of this king. Many other, similar building inscriptions attribute a massive amount of construction to Nebuchadnezzar II, who is one of the best-attested kings of antiquity.

Like other Babylonian kings, Nebuchadnezzar had many temples and statues of the gods built or rebuilt. Nabonidus, who reigned about six years after Nebuchadnezzar died, seemed to prefer the ancient Sumerian moon god, Sin. Temples, statues and inscriptions dedicated to this god were constructed at several cities throughout the empire, causing opposition from the Marduk priesthood due to reversion to a god that had not been prominent for centuries. Nebuchadnezzar, however, probably preferred Nabu the god of wisdom—the god invoked in his name. The massive statue that Nebuchadnezzar erected on the plain of Dura in the province of Babylon may have been a monument to the god Nabu (Daniel 3:1). Alternatively, it could have been an image representing Nebuchadnezzar himself, since it was not typical to display statues of gods outside of their temples. The Verse Account of Nabonidus, from shortly after the time of Nebuchadnezzar, describes a similar situation in which the Babylonian king Nabonidus had a new image of the god Sin constructed and erected. While this action was described in negative terms because of the opposition from the worshippers of Marduk, the basic situation can be compared to that of Nebuchadnezzar and his golden image. The only existing statue currently known that may represent the god Nabu was discovered in a temple of Nabu in Nimrud from the eighth century BC Other ancient statues of this god were probably destroyed, repurposed in later times or have not yet been excavated.

The penalty proscribed for anyone who would not bow down and worship the golden image that Nebuchadnez- zar had built was death by burning in a furnace (Daniel 3:6). Since Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego, given new Babylonian names in an attempt to assimilate these captive Judeans, refused to serve the Babylonian gods and worship the image, they were thrown into the middle of a fiery furnace to be burned alive (Daniel 3:18–23). Interestingly, the practice of execution by burning in a furnace or oven for perceived religious blasphemy is attested in ancient Mesopotamian documents more than 1000 years before the time of Nebuchadnezzar, and it persisted for at least 300 years after. In these texts, the word for the place of burning, translated as “oven” or “kiln,” is the equivalent of the Aramaic word used for the furnace in the book of Daniel. The most relevant of these texts comes from the sixth century BC and approximately the reign of Nebuchadnezzar. The Letter of Samsu-iluna is preserved on a school tablet from the Sippar temple library, and commands that those who have committed blasphemy against the gods be thrown into the kiln to be burned and destroyed by intense flames. The word used indicates a lime kiln, which had an opening at the top in which to place the initial materials for smelting. This appears to be the method used for Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego, as the story describes them as being carried up to the opening of the furnace by the soldiers and falling into the middle of the furnace (Daniel 3:22, 23).

Following the reign of Nebuchadnezzar, Daniel lived through a tumultuous time in the Babylonian Empire in which four kings ascended to the throne over a period of six years. First, Amel-Marduk, son of Nebuchadnezzar, became king after spending an unknown time in prison. Originally his name was Nabu-shuma-ukin, utilising the name of the god Nabu like his father, but later adopting the god Marduk as his patron. His loyalty to Marduk may have been related to his imprisonment. During his time in jail, he wrote a prayer, which is preserved on a cuneiform tablet. He also released the exiled king of Judah, Jehoiachin, from prison, although Jehoiachin was still confined to Babylon (2 Kings 25:27). According to the Babyloniaca, written by Berossus in the third century BC, Amel-Marduk was murdered by his brother-in-law Neriglissar, who then took the throne. According to the Babylonian Chronicle, in his third year he waged a war of defence in Anatolia against King Appuashu.

The Bible book of Daniel never mentions Neriglissar by name, although the Istanbul Prism of Nebuchadnezzar calls him an official and Jeremiah refers to him before he was king as one of the leading officers of Nebuchadnezzar (Jeremiah 39:13). After a four-year reign, he was succeeded by his son, Labashi-Marduk, who was only a boy. After only a few months, Labashi-Marduk was removed from the throne in a palace conspiracy led by Belshazzar and several officers. The scholar Nabonidus then ascended to, or was placed on the throne, although documents dem- onstrate that he was absent from Babylon for most of his reign. Seven years later, the Persians conquered Babylon.

Many historians in the past criticized the book of Daniel because of the reference to a Babylonian ruler named Belshaz- zar. Because no ancient evidence had been recovered that confirmed his existence until archaeological discoveries brought new information to light, sceptics asserted that the book of Daniel was historically inaccurate and full of alleged errors, referencing the “mythical” Belshazzar. Further, Belshazzar the king inexplicably offered third place in the kingdom as a reward rather than the more obvious second place in the kingdom (Daniel 5:7). This puzzled scholars, since Belshazzar is referred to as “king” in the book of Daniel and yet offers the position of third in the kingdom. However, a clay cylinder has been found at the Temple of Shamash in the city of Sippar with a cuneiform inscription about King Nabonidus of Babylon and his son Belshazzar. This artefact is commonly known as the Cylinder of Nabonidus. The relevant portion reads,

“. . . as for Belshazzar my firstborn son, my own child, let the fear of your great divinity be in his heart, and may he commit no sin; may he enjoy happiness in life.”

This document demonstrates that Belshazzar was the firstborn son of the Babylonian king Nabonidus, and therefore part of the ruling line during the lifetime of Daniel. Another cuneiform document, called the Nabonidus Chronicle, explains how the first-born son of Nabonidus was installed as ruler in the absence of his father.

A smaller cuneiform tablet concerning the dedication of a temple to Eanna in Uruk from 539 BC by Nabonidus king of Babylon and provides further historical context for the events. This tablet dates to the last year of the Babylonian empire, ca. 539 BC, just before Cyrus of Persia invaded and captured Babylon, demonstrating that Nabonidus was away from Babylon at this time. Additionally, the fifth century BC Greek historian Xenophon in Cyropaedia wrote that the son of a Babylonian king, also called a king, was ruling in Babylon when the Persians conquered the city. As a composite, these documents reveal that Belshazzar was made acting king in Babylon while his father Nabonidus, the last king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, was away from the capital. Since Nabonidus was still alive and the primary king, he was first in the kingdom, Belshazzar, his son, heir and co-regent, was second in the kingdom, and therefore Daniel could only have been offered third place in the kingdom as a reward for interpreting the message.

The Bible book of Daniel also describes the capture of the capital city of Babylon by the Persians in ca. 539 BC and the subsequent rule of the Persians. The narrative in the book of Daniel indicates that the Persians conquered Babylon and relates how Belshazzar was slain, but records nothing about a battle and mentions a Darius the Mede present at the conquest of the city rather than Cyrus the Great (Daniel 5:28–31). Who was this Darius the Mede, and why was he mentioned instead of Cyrus the Great?

The Nabonidus Chronicle makes it clear that Cyrus was not leading the army at the capture of Babylon, but that a general Ugbaru from Media led the Persian army to Babylon. This general apparently died soon after the successful capture of the city. Various cuneiform docu- ments then attest to a Gubaru, possibly also from Media, who ruled as the Persian governor of Babylon from ca. 539–525 BC Darius the Mede may have been the governor of Babylon known as Gubaru from cuneiform documents. Cyrus II, the Great, ruled the Achaemenid Persian Empire ca. 559–529 BC He combined and expanded the Median and Persian empires into what became the largest empire on earth during ancient times. A major obstacle to the rise of this new Persian Empire was the dominant Neo- Babylonian Empire. According to documents of the period, Cyrus and his armies dealt with this obstacle through military conquest. The Nabonidus Chronicle records the capture of Babylon in 539 BC by the Persians without any mention of a battle, and relates that Cyrus was not present at the initial takeover of the city.

. . . the army of Cyrus entered Babylon without battle. Afterwards, Nabonidus was arrested in Babylon when he returned there . . . [later] Cyrus entered Babylon, green twigs were spread in front of him.

The Cyrus Cylinder affirms the capture of Babylon without a battle:

Marduk, the great lord, a protector of his people, beheld with pleasure his [Cyrus’] good deeds and his upright mind, ordered him to march against his city Babylon. . . . Without any battle, he made him enter his town Babylon, sparing Babylon any calamity.

The Cyropaedia, by Xenophon, records that the Persian army entered Babylon without a battle, adding that they diverted the Euphrates to infiltrate the city. Xenophon also mentions that the acting king, who would have been Belshazzar, was killed after the Persians took the city. Therefore, multiple ancient documents agree with the narrative in the book of Daniel concerning the acting king Belshazzar, his death, and the fall of the city to the Persians.

Given the archaeological and historical evidence available, analysis of the book of Daniel clearly reveals that Daniel lived in Babylon during a transitional period in world history in which the powerful Neo-Babylonian empire rose by defeating the previously dominant Assyria and then fell, being replaced by the massive Achaemenid Persian empire. Specific information within the book also demonstrates that it was written roughly contemporary with the events it describes, and that it contains accurate historical accounts of people and events in Babylon during the sixth century BC .