In the 1840s, Vienna's Allegmeine Krakenhaus was one of the world’s foremost teaching hospitals. However, in its maternity wards, one in six women died in childbirth, a shocking mortality rate, but not dissimilar to any other in the western world. Reasons given by obstetricians included constipation, fear, delayed lactation and poisonous air.

Upon death, autopsies were performed on these women by physicians, who immediately after the procedure, without washing their hands or using sterile gloves, performed pelvic examinations on the living in the maternity wards!

Early in the 1840s, Ignaz Semmelweis took charge of one of the obstetrical wards. After three years of observation, he discovered that it was the women who were examined by doctors immediately after performing the autopsies, who died. He therefore ruled that all doctors participating in autopsies must thoroughly wash their hands before examining any patients in his ward. The death rate in his ward immediately plummeted. However, the prejudiced doctors did not like his “new” ideas. His contract was not renewed, his rule overturned and the mortality rate soared once again.

Unknown to Semmelweis, his progressive ideas and procedures had been practiced thousands of years before!

Ancient Egyptian Medicine

In its time, medical knowledge and practice in ancient Egypt was likewise revolutionary, with Egypt’s physicians showing great initiative and an impressive knowledge of the human body, its organ function, system’s workings and the treatment of illness and disease.

Sources of Information

Prior to the nineteenth century, our only sources of information regarding ancient Egyptian medicine and practice were from Homer (c. 800 BC), Herodotus (440 BC) and Pliny the Elder (a.d. 23 – a.d. 79). Hippocrates, known as the father of medicine, and Galen studied medicine in Egypt and acknowledged the contribution of ancient Egyptian medicine to Greek medicine. Interestingly, in about 600 BC, the ancient Hebrew religious texts (the biblical Old Testament) referred to Egyptian medical practice (Jeremiah 46:11).

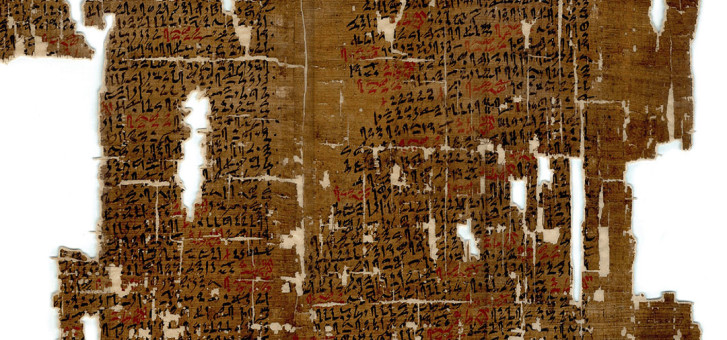

Medical Papyri

Following the deciphering of Egyptian hieroglyphs, a number of papyri relating to medical matters were translated. These papyri revealed a great deal about ancient Egyptian medical knowledge and practice. Following are some such examples:

Eber Papyrus (1550 BC) This papyrus contains the largest record of ancient Egyptian medicine ever unearthed, including some 700 magical formulas and remedies. Many of its incantations were meant to turn away the demons believed to have caused diseases in the first place. It reveals that the Egyptians believed the heart to be the centre of the blood supply, with vessels connected to every part and organ of the body. They also believed the heart was the “meeting point” of vessels that carried all the fluids of the body—blood, tears, urine and semen. Depression, dementia and other mental disorders are also detailed in the papyrus. It contains chapters on intestinal disease and parasites, eye and skin problems, dentistry and surgery, and contraception and gynaecology.

Edwin Smith Papyrus (1600 BC) It is the world’s oldest surviving surgical manual, and is a truly scientific medical document, devoid of theorising and magic. It describes in detail anatomical observations and the examination, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of some 48 types of medical problems. Treatments described contain descriptions of closing wounds with sutures, the prevention and cure of infection using honey and mouldy bread, the use of raw meat to stop bleeding, and immobilisation of the head in spinal cord injuries. It reveals that ancient Egyptian medical practice was sophisticated and practical.

Kahun Gynaecological Papyrus (1900 BC) This is the oldest medical papyrus yet discovered. It mentions methods to ascertain pregnancy, sex of the foetus, diseases of women and prescriptions that included drugs, fumigations, pastes and vaginal application.

Other Medical Papyri. These include the Hearst (1550 BC), Erman (1550 BC), Berlin (ca. 1350—1200 BC), London (1350 BC), Chester Beatty (1200 BC), Carlsberg No. VIII (1200 BC), Brooklyn Museum (380–343 BC), Ramasseum No. III, IV and V (1900 BC) and Magical Papyrus of Leyden papyri. They contain, among other things, descriptions of new diseases, the treatment of fractures and animal bite, the care of infants, popular charms for childbirth, methods for ascertaining the sex of unborn children, incantations against various diseases, gynaecological prescriptions, obstetric prognoses and the relaxation of stiffened limbs.

Remains of Mummies

Much has been learned about the level of Egyptian health and healing from the examination of mummies using modern technology. These methods range from a straightforward examination of skeletal remains to the truly sophisticated, including radiological imaging and cephalometric tracing (the analysis of the dental and skeletal relationships in the head); computed tomography or CT scanning; three-dimensional CT reconstruction; histological microscopic examination of dried tissue; blood grouping and other biochemical and immunological investigations; nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) studies; neuropathological studies; endoscopy; electron microscopy; immunohistochemistry; and DNA analysis.

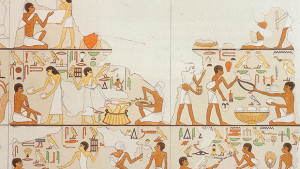

Egyptian Artistic Representations

Ancient Egyptian artists were keen observers and revealed in their drawings the actual physical deformities of their subjects including hunchback, scrotal hypertrophy and poliomyelitis deformities

Medical Practitioners

Egyptian medical practice encompassed many fields including pharmacology, dentistry, gynaecology, crude surgery, general healing, autopsy and mummification. Due to the fact that priests were involved in the embalming process (which required knowing something of the human body), many priests were also physicians of sorts. Above all, mummification gave ancient Egyptian priestphysicians the opportunity to examine and observe many specimens over long periods, thereby greatly increasing their knowledge of human anatomy.

The physicians knew the body had a pulse that was associated with the functioning of the heart, and they had a basic knowledge of a cardiac system. They were trained in, and good at, practical first-aid, and could successfully fix broken bones and dislocated joints. They performed basic surgery close to, or on, the skin’s surface very well, and were effective in stitching surface wounds. They treated inflammation with excellent healing remedies, binding plant products, such as willow leaves, onto the affected areas. Circumcision of male babies was common. However, lacking anaesthetics, they did not perform surgery deep inside the body.

Surgeons had many instruments, such as forceps, spoons, pincers, saws, containers of burning incense (aromatherapy), hooks and knives, some of which can be seen in an inscription at the Temple of Kom Ombo (see image on previouse page). Prosthetics existed, but some scholars believe they were probably not very practical and were used either to make the dead look more presentable during funerals or were simply for decorative purposes. However, research by Dr Jacky Finch of the University of Manchester on two ancient Egyptian artificial toes, has demonstrated they would have aided walking, thus likely making them the oldest discovered prosthetic devices. Many doctors believed evil spirits blocked “channels” in the body, which affected the way the body functioned. It was believed the channels provided the body with routes for good health. The Egyptians believed the heart was the centre of some 46 such channels—the systems of the body—and to a limited sense they were right. Our circulatory, respiratory, renal and intestinal systems are pretty much tube-like, after all! However, they never realised that the “channels” each had different functions. Their medical practice involved finding ways to unblock the channels. Through trial and error and some basic science, including the use of laxatives for example, to unblock the channels, the profession of a medical doctor emerged, with doctors using a combination of natural remedies combined with incantations and magic.

Dangeous Medical Practices

But while medical practice in ancient Egypt was millennia ahead of other civilisations, it often fell far short of sound scientific medical advice. For example, the medical remedies for hair problems found in the Ebers Papyrus mentioned above is somewhat questionable (as are many today, I might add): “To prevent the hair from turning grey, anoint it with the blood of a black calf which has been boiled in oil, or with the fat of a rattlesnake.” And how about this one for hair loss: “When it falls out, one remedy is to apply a mixture of six fats, namely those of the horse, the hippopotamus, the crocodile, the cat, the snake and the ibex. To strengthen it, anoint with the tooth of a donkey, crushed in honey” (from S.E. Massengill, A Sketch of Medicine and Pharmacy).

But that’s not all. To save those bitten by poisonous snakes, physicians gave “magic water”—water poured over an idol—to drink. Embedded splinters were treated

worm’s blood and asses’ dung. Since tetanus spores reside in dung, little wonder those with splinters often died of lockjaw.

The Ebers Papyrus contains hundreds of medical remedies using “drugs,” which include lizard’s blood, swine’s teeth, putrid meat, stinking fat, moisture from pig’s ears, goose grease, asses’ hooves, animal fats, human excreta, and various applications of donkey, antelope, dog, cats, and even flies.

Interestingly, around the time the Ebers Papyrus was being written, the great Hebrew liberator Moses was born in Egypt. He was raised and educated as an Egyptian prince, living the royal life in a palace (see Acts 7:20–22). No doubt he was knowledgeable of Egyptian medical practice. Yet what is most remarkable is that across his entire writings (the Pentateuch or first five books of the Jewish and Christian Bible), which contain much instruction in the principles of personal and community health, there is no mention of the “quackery” found in the Ebers Papyrus, which came from the most advanced medical schools of his day. Rather, and amazingly, the only principles and practices he outlines have sound and verified scientific and medical justification in the contemporary world.

Egyptian Health

Public Health

While cleanliness was important in Egyptian life, it was promoted for social and religious reasons rather than for health. However, there was no public health infrastructure, as we know it today, with sewage systems and public hygiene.

Diet

Modern science has amply shown how health and longevity are closely tied to diet. An examination of the ancient Egyptian diet is revealing. Beer and bread—much like our society today—were ubiquitous in ancient Egypt. Complementing them were vegetables, of which the most common were long-shooted green scallions and garlic, with both also having medical uses. The most common fruits were dates and figs. Meat was eaten, including cattle, sheep, goats and pigs (the last at one time thought to have been taboo). Beef, being more expensive, would have been eaten once or twice a week, reserved mostly for royalty. However, excavations at the Giza workers village discovered the slaughter of beef, mutton and pork on a massive scale. Researchers estimate that workers at the Great Pyramid ate beef daily. Mutton and pork were more common. Poultry and fish were available to all but the poorest, and mice and hedgehogs were also eaten. Diet was an important health factor in ancient Egypt. Examination of mummies reveals that dental caries, while rare in the predynastic period, became more frequent with the development of civilisation, especially among the wealthy.

Diseases

Beside dental caries, autopsies performed on Egyptian mummies reveal an array of other diseases, including heart disease, cancer, vascular diseases, arthritis, hepatitis and trichinosis. Professor Rene Dubos in his book Mirage of Health, says:

. . . the list of diseases found in mummies reads almost like the catalog of a pathological museum and includes silicosis, pneumonia, pleurisy, kidney stones, sinusitis, gallstones, cirrhosis of the liver, mastoiditis, appendicitis, meningitis, smallpox, leprosy, malaria, tuberculosis, congenital atrophy of the liver.

Mummies have well-preserved blood vessels and reveal positive evidence of vascular diseases of the aorta and coronary arteries. Medical science has proved a correlation between heart disease and diets high in animal fat, which are high in cholesterol. As seen above, it appears that many Egyptians ate meat regularly.

Ancient Hebrew Disease Prevention

At the time of the great Hebrew exodus from Egypt under Moses, the Bible records an incredible promise given to him by God on behalf of the new nation of Israel. Moses records it as follows:

"If you listen carefully to the Lord your God and do what is right in his eyes, if you pay attention to his commands and keep all his decrees, I will not bring on you any of the diseases I brought on the Egyptians, for I am the Lord, who heals you.” (Exodus 15:26, NIV)

What a promise! If the followed his instructions, God would protect them from the diseases the Egyptians suffered. So what did He instruct?

While some medical practices in the Pentateuch are similar to those found in the ancient Egyptian papyri, conspicuously absent in the Pentateuch are the harmful malpractices of the Egyptians. Moses writings contain the most advanced—sound and flawless—medical practices recorded. In fact every statement he wrote concerning the medical well-being of the Israelites could be implemented today, and be in accord with modern medicine and public health in relation to the spread of germs, epidemic disease control, sanitation, dietary principles and many other medical and scientific discoveries. The reasoning might be different—adapted to the context and (lack of) knowledge of the times, but sound nevertheless.

Which brings us back to Dr Ignaz Semmelweis and his hand-washing rules instituted in his Vienna hospital. Nearly 3400 years before his ground breaking discovery, that cleansing the hands after touching a cadaver resulted in the preventing of deaths, Moses, as recorded in (Numbers 19:11–22), gave these emphatic instructions concerning the matter.

“The one who touches the corpse of any person shall be unclean for seven days. That one shall purify himself from uncleanness with the water on the third day and on the seventh day, and then he will be clean.” (vv. 11, 12)

This Biblical method included the use of running water with time intervals for drying and exposure to sunlight to kill bacteria not washed off. The technique even required those who had contacted the dead to change into clean, dry clothing. These biblical procedures were so different and so much more effective than anything humans have ever devised. One has to wonder as to their Source. The scriptural principles given to Israel included far more than the hygienic washing of hands; they contain quarantine rules to contain communicable disease, for example. Kyle Butt, in an excellent article in Apologetics Press, quotes Roderick McGrew in Encyclopedia of Medical History (1985):

“The idea of contagion was foreign to the classic medical tradition and found no place in the voluminous Hippocratic writings. The Old Testament, however, is a rich source for contagionist sentiment, especially in regard to leprosy and venereal disease.” (pp. 77, 78)

Until the end of the seventeenth century, hygienic conditions in European cities were deplorable, with human excreta dumped into streets, flies and rodents abounding, spreading fatal disease. In the Industrial Revolution, people often lived in dark, airless tenement houses, with 30 families sharing a toilet, which probably overflowed into a cesspool. Little wonder there were epidemics of typhus, typhoid, dysentery and cholera.

So consider Mosses’ sage instructions to the millions of Jewish former slaves under his care. The Israelites were told to make their toilets outside their camping area, burying their excrement: “Designate a place outside the camp where you can go to relieve yourself. As part of your equipment have something to dig with, and when you relieve yourself, dig a hole and cover up your excrement.” (Deuteronomy: 23:12, 13, NIV)

(Deuteronomy: 23:12, 13, NIV) Consider his instruction re diet: “Say to the Israelites: ‘Do not eat any of the fat of cattle, sheep or goats” (Leviticus 7:23, NIV). Medical science has proved the correlation between heart disease and diets high in animal fat. With some Egyptians consuming high volumes of meat, it is no surprise that mummies reveal a high incidence of cardiovascular diseases, such as atherosclerosis. Moses’ prohibition on the eating of fat reinforces the view of heart specialist Dr Paul Dudley White, who treated President Eisenhower, who many years ago asserted “that a few years from now we medical men may repeat to the citizens of the United States of America the advice that Moses was asked by God to present to the children of Israel 3000 years ago.”

Dietary regulations given in the Pentateuch also included the types of animal flesh to be consumed—that is, so-called “clean” and “unclean” foods, first recorded in the Bible in the story of Noah, long before the Israelite nation emerged (Genesis 7:1,2; Leviticus 11:1–23; Deuteronomy 14:4–20). “Clean” land animal foods were those described as chewing the cud and having a cloven (divided) hoof (cow, sheep and goat), while the “unclean” were animals that did not possess both of these features (rabbit, camel, horse and pig). The “clean” water creatures had to have both fins and scales to be classed by God as edible, while the edible “clean” birds were named by their kinds.

The two groups are a general division of scavenger and herbivore. Pigs, being scavengers, consume parasites and bacteria when eating the carcasses of other animals, which then reside in the pigs’ tissue. A failure to cook the meat thoroughly can result in numerous harmful effects, such as small tumours, epileptic convulsions, trichinosis and toxoplasmosis—a disease affecting the nervous system (R.K. Harrison in “Heal,” International Standard Bible Encyclopedia). Trichinosis was commonly found in the autopsies of mummies.

Shellfish fall outside the definition of “clean” foods. A delicacy today, many to their peril have realised the pain from eating ill-prepared or contaminated oysters, with food poisoning and even death occurring. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration warns people of the dangers of eating raw or partially cooked oysters, as some raw oysters contain the dangerous bacteria Vibrio vulnificus.

Much more could be said—in fact much has—of the numerous scientific discoveries that support the amazing, insightful personal and public health principles and dietary guidelines outlined by Moses. The great archaeologist, W.F. Albright, noted that “thanks to the dietary and hygienic regulations of Mosaic law . . . subsequent history has been marked by a tremendous advantage in this respect held by Jews over all other comparable ethnic and religious groups” (Yahweh and the Gods of Canaan).

You don’t have to be religious or a person of faith to believe and follow the health principles of Moses and the Bible. After all, they’re employed in every modern hospital; they’re scripted in public health brochures and promotions and outlined in the dietary guidelines of all advanced nations.

Sources

- Ancient Bible Health Secrets Revealed Today! Hope of Israel Ministries (http://www.hope-ofisrael.org/bihealth.htm)

- Ancient Egyptian Cuisine (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egyptian_cuisine)

- “Ancient Egyptian Medicine: The Study and Practice of Medicine in Ancient Egypt,” in Ancient History Encyclopedia, http://www.ancient.eu/article/50/

- Ebers Papyrus (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ebers_Papyrus)

- Ebeid Nabil I. Egyptian Medicine In The Days Of The Pharaohs

- McGrew, Roderick. Encyclopedia of Medical History. 1985 (London: Macmillan).

- Christian, Nordqvist. Ancient Egyptian Medicine in A History Of Medicine for Medical News Today, August 9, 2012 (http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/info/medicine/ancient-egyptianmedicine.php)

- McMillen S.I. None of These Diseases, Oliphants (1963)

- But Kyle. Scientific Foreknowledge and Medical Acumen of the Bible (http://www. apologeticspress.org)